The U.S. Postal Service consistently tops the favorability list in Pew Research Center’s periodic surveys of public views of government agencies. This year, 91% of Americans – and equal 91% shares of Democrats and Republicans – had a favorable view of the agency.

But the Postal Service, already in a deep financial hole, now finds itself caught in a political firestorm. President Donald Trump has long claimed that package shippers, particularly online retailers such as Amazon, aren’t paying enough. He has blocked a $10 billion congressionally approved emergency loan to the cash-strapped agency; threatened to veto any future emergency funds unless the Postal Service quadruples its package shipping prices; and named one of his major donors as the new postmaster general.

Democrats, many outside analysts, Postal Service advocates and the agency itself dispute Trump’s contention that low package rates are the main driver of its money woes. They say that without relief, the Postal Service could run out of operating cash as soon as this fall. A coalition of retailers plans a $2 million lobbying and ad campaign to oppose Trump’s plans and support a massive rescue package.

How has the Postal Service, which turns 50 next year, wound up in such a predicament? We crunched the numbers to find out.

We decided to take a look at the U.S. Postal Service after the latest Pew Research Center survey once again placed it at the top of the list of government agencies that Americans view favorably. To analyze the Postal Service’s operations, finances and workforce demographics, we drew from a range of sources. Operating and financial data were compiled from the Postal Service’s annual reports to Congress and the Postal Regulatory Commission; additional background was obtained from news reports and reports from the Congressional Research Service. Demographic data was drawn from the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2018 American Community Survey.

For this analysis, racial groups include those who report being only one race and are non-Hispanic. Hispanics are of any race.

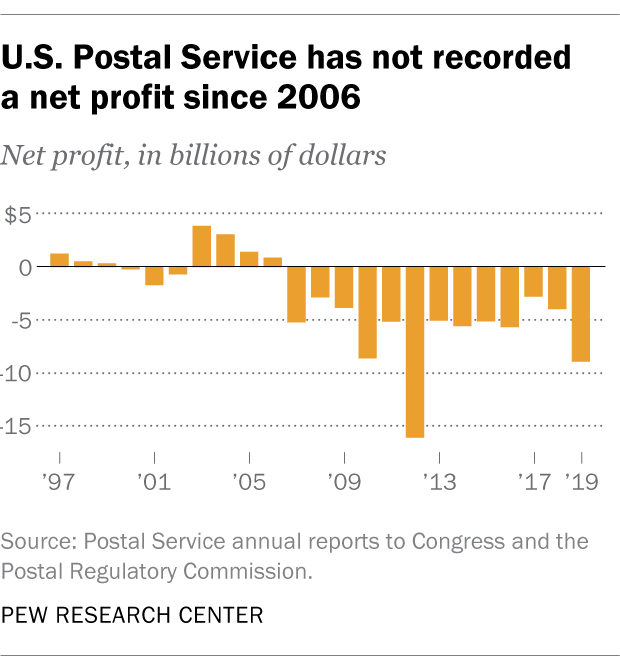

1When Congress created the Postal Service to replace the old Post Office Department, it mandated that the new agency support itself through its own revenues, rather than relying on federal appropriations. However, the last year the Postal Service recorded any profit was 2006, and its cumulative losses since then totaled $83.1 billion as of March 31. The Postal Service also owes $11 billion to the Treasury and more than $59 billion in required but unpaid contributions to its employee pension and retiree-health funds.

1When Congress created the Postal Service to replace the old Post Office Department, it mandated that the new agency support itself through its own revenues, rather than relying on federal appropriations. However, the last year the Postal Service recorded any profit was 2006, and its cumulative losses since then totaled $83.1 billion as of March 31. The Postal Service also owes $11 billion to the Treasury and more than $59 billion in required but unpaid contributions to its employee pension and retiree-health funds.

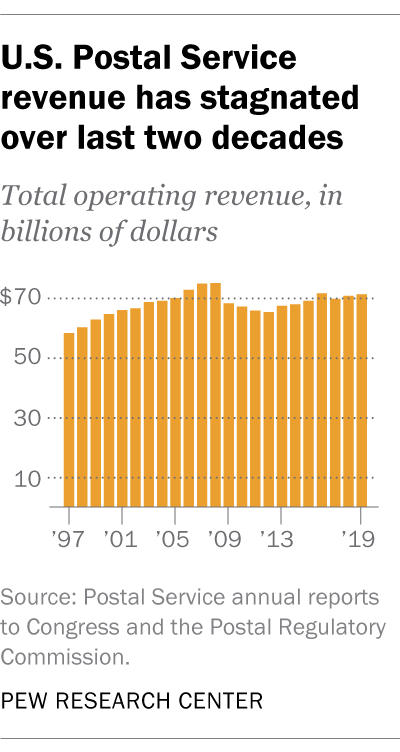

2Compounding the Postal Service’s debt problems has been a lack of revenue growth. The agency’s total revenue in fiscal 2019 was $71.2 billion, enough to place it 43rd on the Fortune 500 (higher than Intel) if it were a private company. But Postal Service revenue has mostly fallen or stagnated since 2008, when it hit a record $74.9 billion.

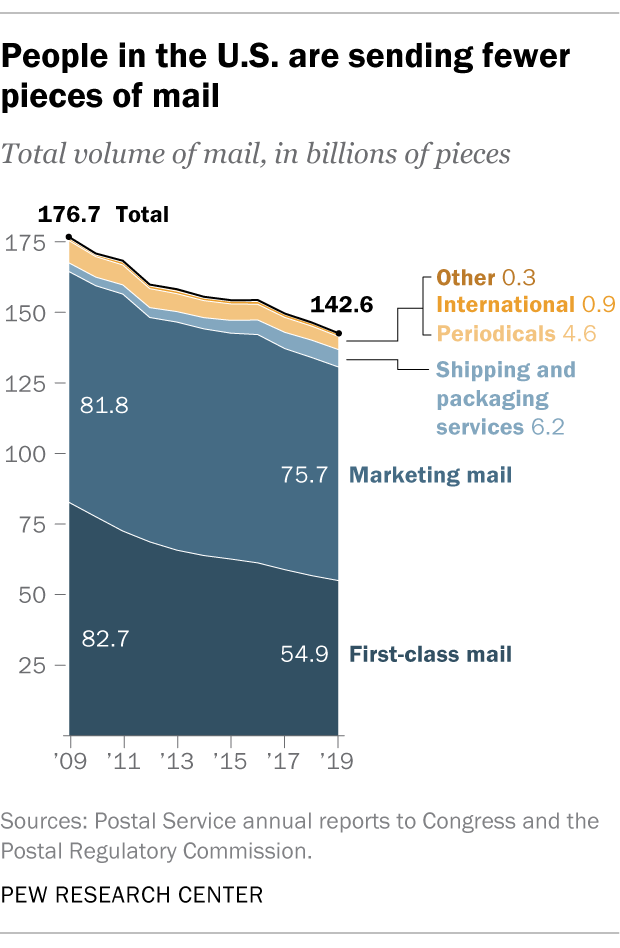

3One key reason the Postal Service’s revenue hasn’t kept pace with expenses is that it’s delivering a lot less mail than it used to. In 2000, the agency delivered 207.9 billion pieces of mail, including everything from postcards to packages. Last year, it delivered 142.6 billion pieces, a 31.4% decline. The drop-off has been especially steep in first-class mail – a highly profitable product line that saw a 33.6% drop in the number of pieces of mail sent over the past decade – and in periodicals, down 41.3% over the same period.

4One bright spot has been shipping and packaging services. Volume in that category has doubled over the past decade, to nearly 6.2 billion pieces last year. Unlike first-class or marketing mail, most of the agency’s shipping and packaging offerings are considered “competitive” services, meaning the Postal Service has more leeway to set rates in line with what it thinks the market will bear. In fiscal 2019, shipping and packaging accounted for just 4.3% of total mail volume but 32% of revenue. By contrast, marketing mail made up 53% of volume but generated just 23% of overall revenue.

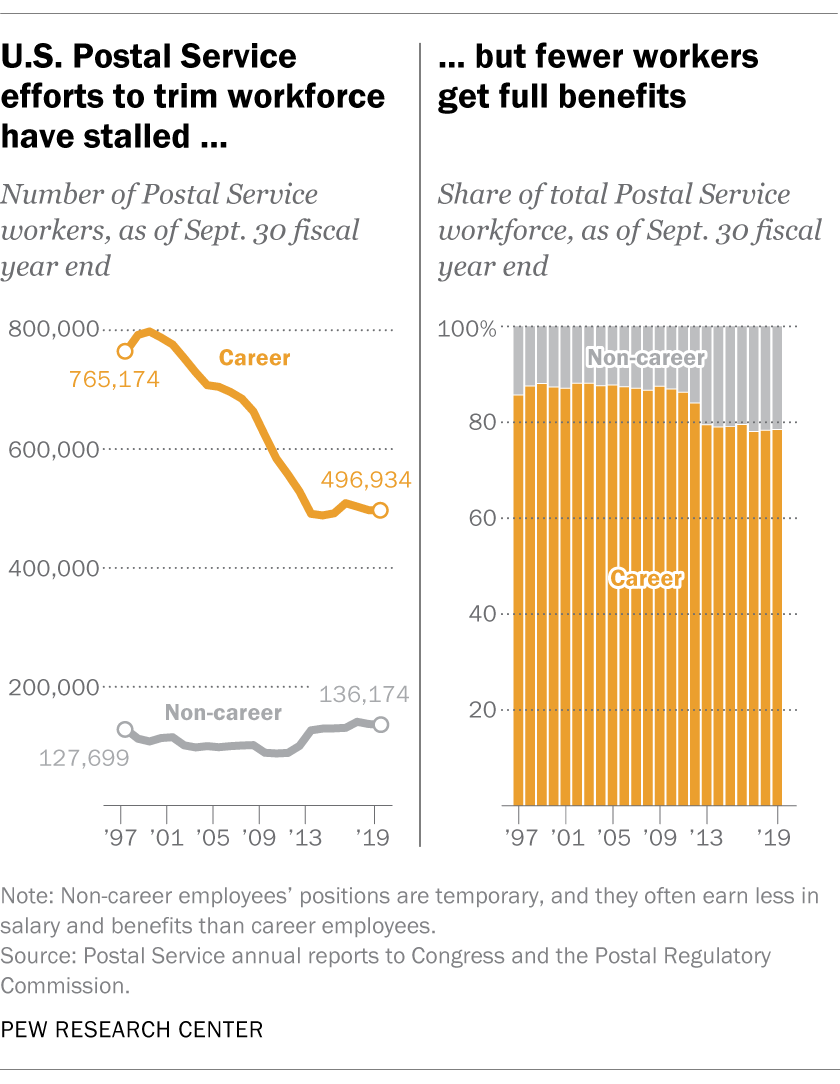

5To address its ongoing financial problems, the Postal Service’s management has urged Congress and the Postal Regulatory Commission to authorize major changes in the way it does business – so far to no avail. The proposals include requiring postal retirees to enroll in Medicare, which would relieve the agency of having to pre-fund retiree health benefits, and giving the agency more freedom to raise rates on its non-competitive (i.e., monopoly) services. In the meantime, the agency has tried to save money in other ways, such as by shrinking and reshaping its workforce. Through retirement incentives and attrition, the Postal Service has whittled its workforce down to 633,108 employees as of the end of fiscal 2019, 30% below its peak year of 1999. Just over a fifth (21.5%) of those workers are considered “non-career,” meaning their positions are temporary and they often earn less in salary and benefits than “career” employees.

5To address its ongoing financial problems, the Postal Service’s management has urged Congress and the Postal Regulatory Commission to authorize major changes in the way it does business – so far to no avail. The proposals include requiring postal retirees to enroll in Medicare, which would relieve the agency of having to pre-fund retiree health benefits, and giving the agency more freedom to raise rates on its non-competitive (i.e., monopoly) services. In the meantime, the agency has tried to save money in other ways, such as by shrinking and reshaping its workforce. Through retirement incentives and attrition, the Postal Service has whittled its workforce down to 633,108 employees as of the end of fiscal 2019, 30% below its peak year of 1999. Just over a fifth (21.5%) of those workers are considered “non-career,” meaning their positions are temporary and they often earn less in salary and benefits than “career” employees.

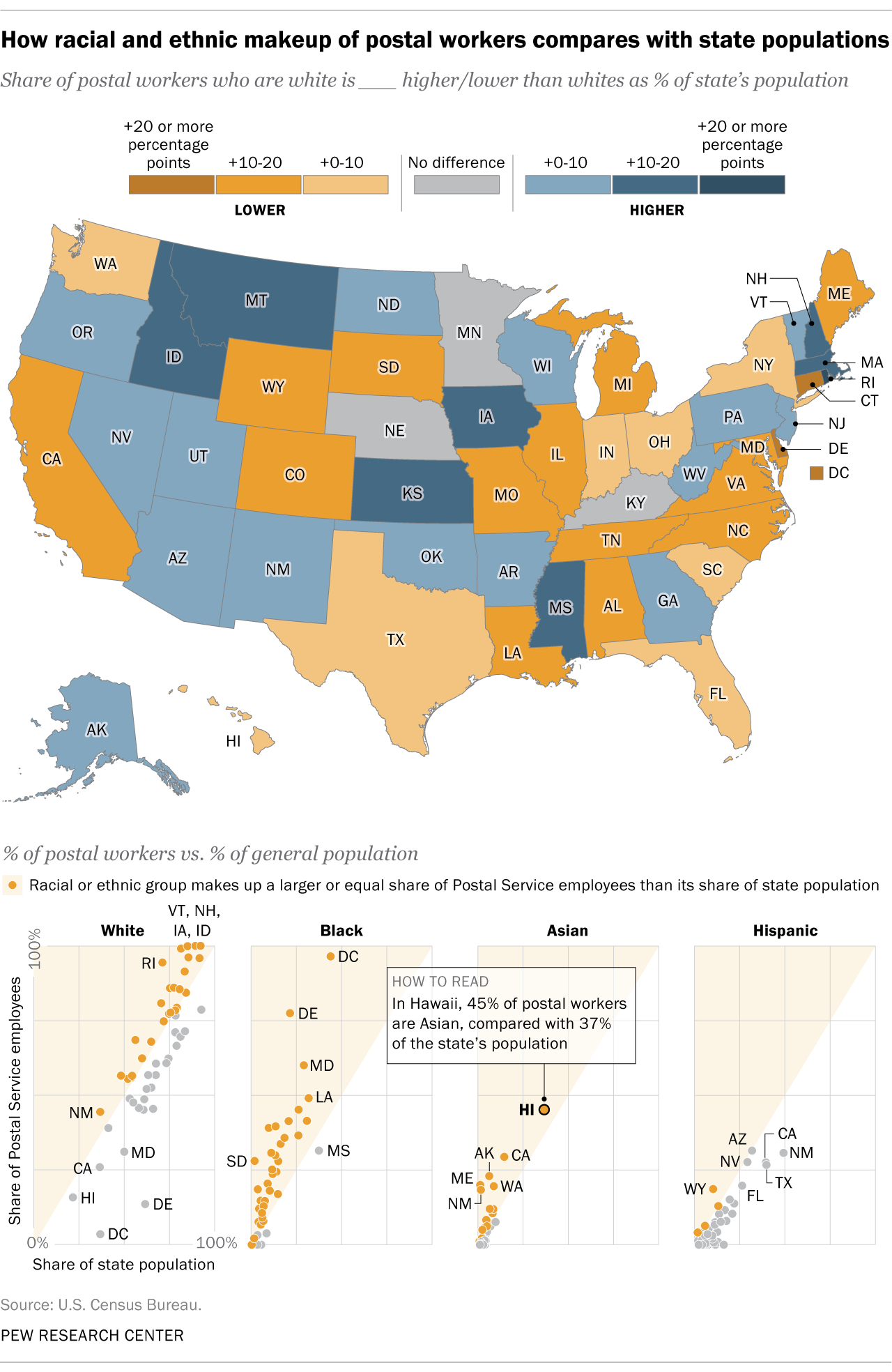

6Efforts to shrink the Postal Service payroll would likely affect racial and ethnic minorities, women and veterans more than others. Postal workers are more racially and ethnically diverse than the U.S. labor force as a whole, according to Census Bureau data from 2018, the most recent year available. About six-in-ten of the agency’s employees – including mail carriers, postal clerks, and mail sorters and processors – are non-Hispanic white (57%), compared with 78% of the overall U.S. workforce. Around a quarter (23%) of Postal Service workers are black, 11% are Hispanic and 7% are Asian. In contrast, black Americans make up 13% of the national workforce, Hispanics 17% and Asian Americans 6%.

In 38 states, 50% or more of Postal Service employees are white, but racial and ethnic differences do exist. For example, in the District of Columbia, Delaware and Maryland, 60% or more of postal workers are black. In Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada, California and Texas, about three-in-ten of them are Hispanic. In Hawaii, slightly fewer than half (45%) of Postal Service employees are of Asian origin, and 25% are of two or more races.

In 38 states, 50% or more of Postal Service employees are white, but racial and ethnic differences do exist. For example, in the District of Columbia, Delaware and Maryland, 60% or more of postal workers are black. In Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada, California and Texas, about three-in-ten of them are Hispanic. In Hawaii, slightly fewer than half (45%) of Postal Service employees are of Asian origin, and 25% are of two or more races.

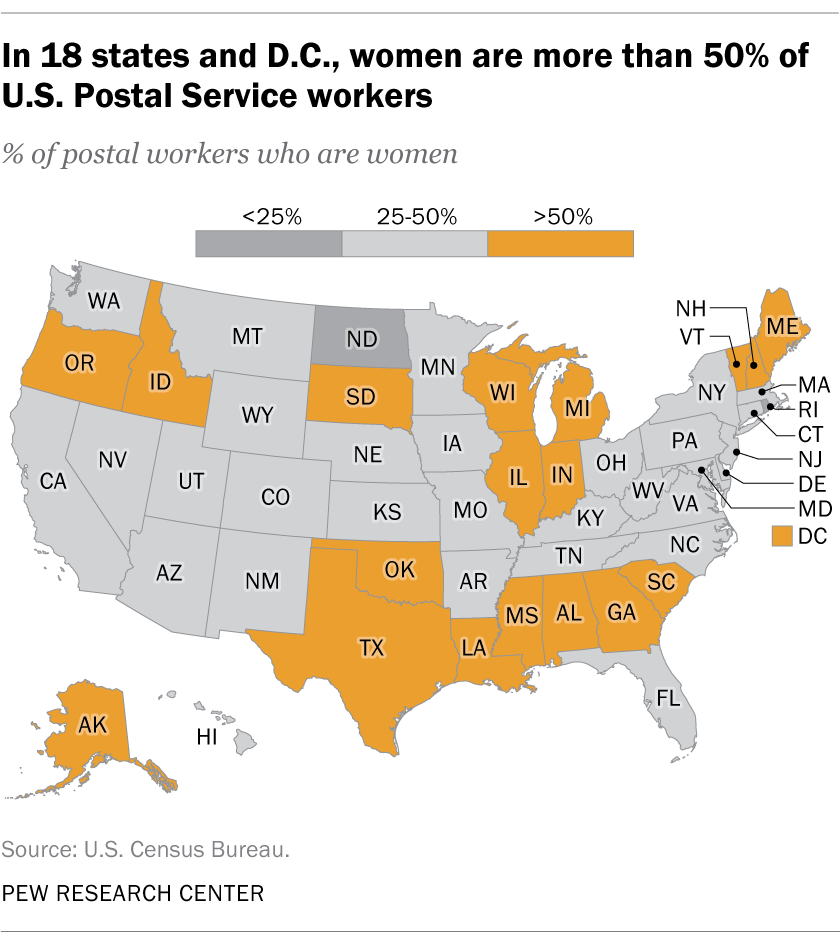

7 In 18 states and the District of Columbia, women make up half or more of Postal Service employees. In D.C., 74% of Postal Service workers are women, and women account for around six-in-ten postal workers in Idaho, Alabama and South Dakota. Nationally, slightly fewer than half of postal workers are women (45%), in line with the U.S. workforce.

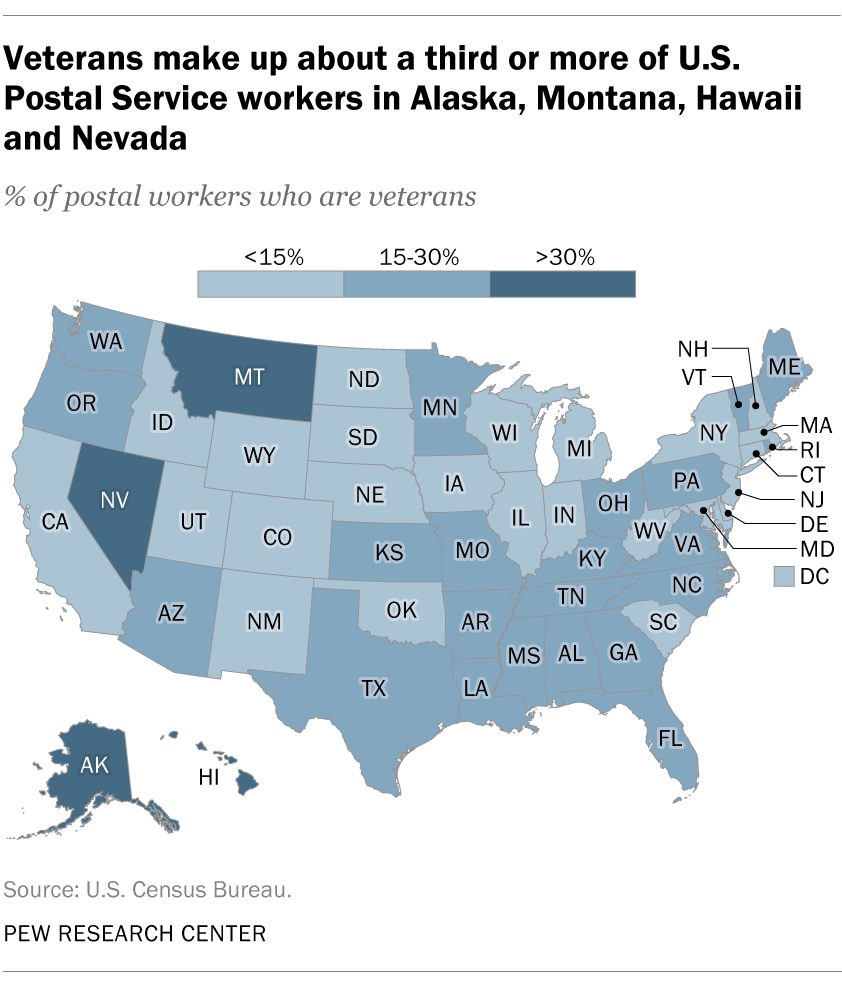

8The Postal Service, as of 2018, employs more than 100,000 military veterans, who make up 16% of its workers nationally. Veterans account for just 5.8% of all employed Americans, according to data for 2019.

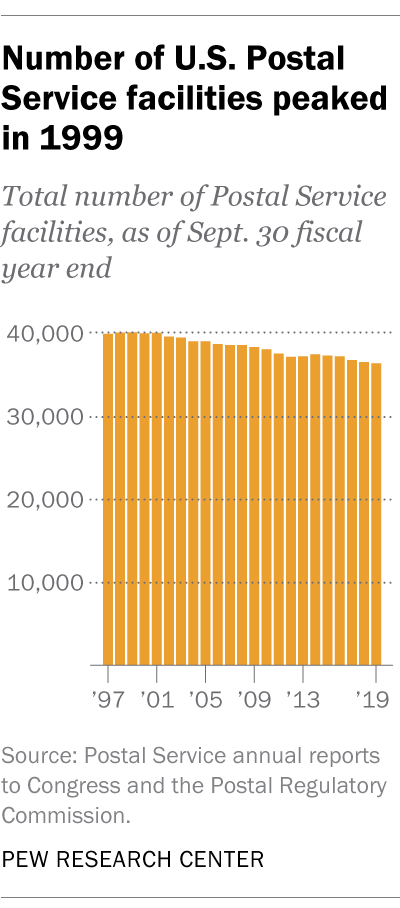

9The Postal Service also has been trying to reduce its physical footprint, despite resistance from communities and, often, their representatives in Congress. The total number of Postal Service facilities has fallen 9.3% over the past two decades, from more than 38,000 nationwide in 1999 to around 34,600 as of Sept. 30. However, the number of individual mailboxes, P.O. boxes, and other “delivery points” – currently 159.9 million – typically grows by 1 million or more each year, adding to the Postal Service’s challenges.