In addition to its public health consequences, the coronavirus pandemic is likely to lead to an increase in government debt around the world. The global economy is projected to shrink 3% this year – a downturn that would likely cause tax revenues to fall – even as governments in the United States, Europe and elsewhere spend trillions of dollars on emergency relief measures to try to contain the damage.

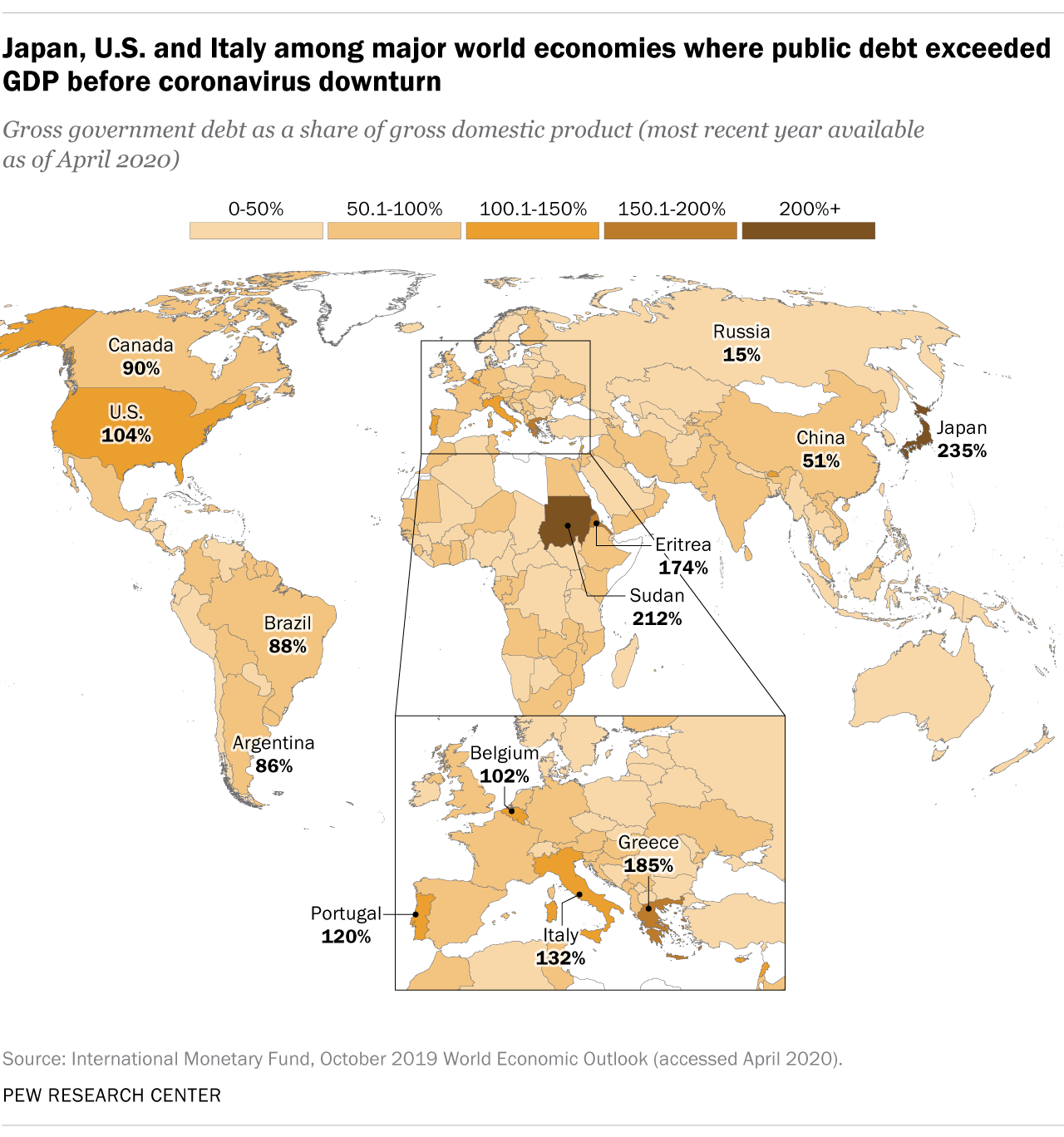

For some governments, the debt incurred on COVID-19 relief will add to the considerable red ink already on their ledgers before the pandemic arrived. Leading up to the crisis, government debt accounted for a large chunk of gross domestic product – or exceeded it – in dozens of countries, including some of the world’s biggest economies, according to data published by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in October 2019. (This analysis focuses on “gross government debt,” including intragovernmental debt. It excludes private debt held by businesses and individuals.)

Government finances are in the spotlight amid the global economic downturn caused by the coronavirus. This analysis of government debt-to-GDP ratios is based on data for more than 180 countries from the International Monetary Fund, published in October 2019. The analysis uses the most recent available year of data for each country (in most cases 2018). All references to government debt refer to “gross government debt,” encompassing debt held by all levels of government. Private debt, such as debt held by businesses and individuals, is excluded from the analysis.

As a share of its economy, no country has a bigger debt load than Japan, where gross debt accounted for 235% of GDP in 2017, the most recent year for which the IMF has final data. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s government pushed through a sales tax hike in fall 2019 in part to help pay down the debt, which, as a share of GDP, is much higher than that of most other nations, including Greece (185% as of 2018). Abe has held out the possibility of reversing the tax increase if its economic effects are harmful.

Japan is not the only major economy where government debt exceeded or nearly equaled GDP before the outbreak. In 2018, debt accounted for 132% of GDP in Italy, 104% in the U.S., 98% in France, 90% in Canada and 87% in the United Kingdom. Along with Japan, all of these countries are part of the Group of Seven, a forum for the world’s leading industrial economies. In the remaining G7 member, Germany, debt accounted for 62% of GDP in 2018.

Japan is not the only major economy where government debt exceeded or nearly equaled GDP before the outbreak. In 2018, debt accounted for 132% of GDP in Italy, 104% in the U.S., 98% in France, 90% in Canada and 87% in the United Kingdom. Along with Japan, all of these countries are part of the Group of Seven, a forum for the world’s leading industrial economies. In the remaining G7 member, Germany, debt accounted for 62% of GDP in 2018.

Other large economies where debt accounted for a comparatively large share of GDP in 2018 include Spain (97%), Brazil (88%) and Argentina (86%).

In China – which has the second-largest economy in the world after the U.S. – debt accounted for around half of GDP (51%) in 2018. China reported April 17 that its GDP declined for the first time in decades in the first quarter of 2020, falling 6.8% from the first quarter of 2019.

Public debt was high by historical standards before COVID-19 outbreak

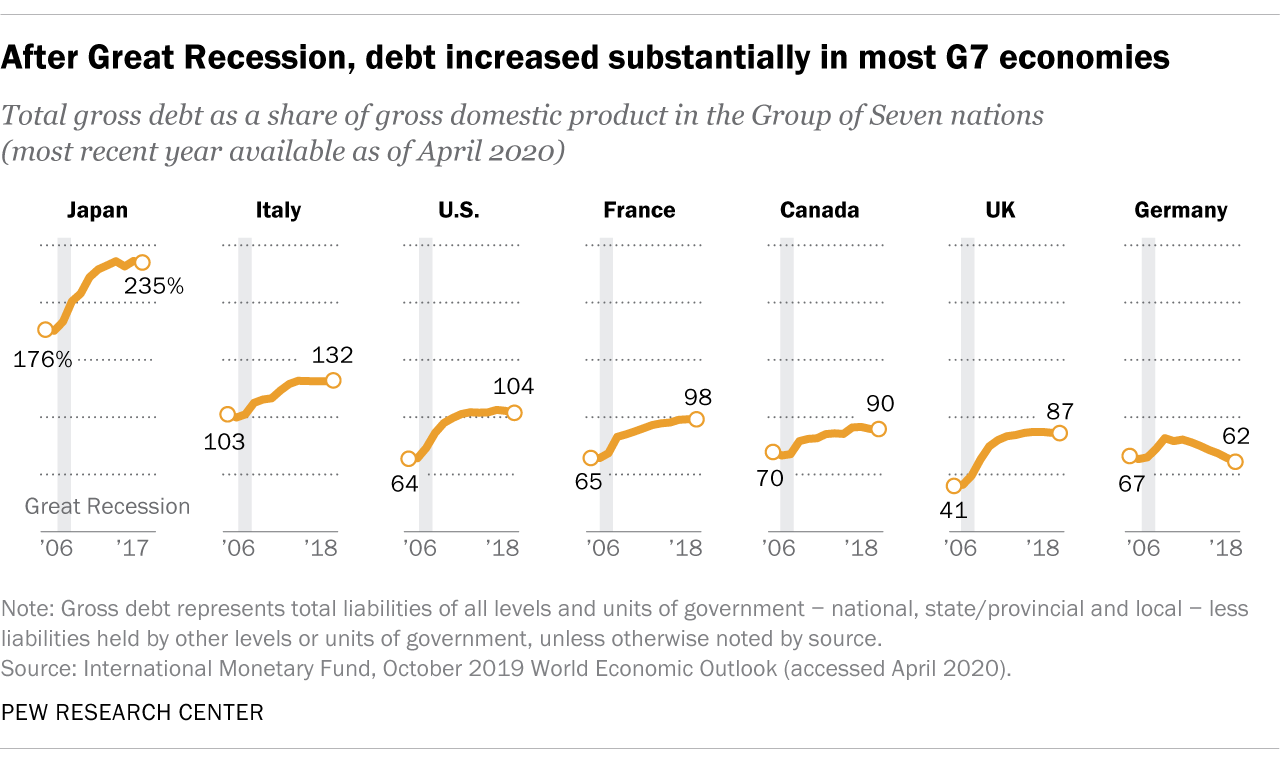

Government debt in most countries was running high by historical standards before the coronavirus outbreak, according to a December 2019 analysis by the IMF. In almost 90% of countries described by the IMF as “advanced economies,” debt-to-GDP ratios were higher in recent years than they were during the last global recession, which began in late 2007 and lasted until mid-2009.

In most G7 countries, debt went up as a share of GDP in the years following the Great Recession. In the U.S., for example, debt accounted for 64% of GDP in 2006 but rose to more than 100% of GDP in 2012 and subsequent years. In Italy, where the coronavirus has taken a serious toll, government debt was already slightly higher than GDP (103%) leading up to the last recession in 2006. By 2013, debt had increased to 129% of Italy’s GDP, where it has essentially stayed since.

Public debt has also been on the rise in “low-income developing countries” (defined as those with per-capita incomes below a certain threshold), according to the IMF’s December analysis. On April 23, the United Nations’ trade and development panel warned of a “looming debt disaster” in developing countries and called for steps including $1 trillion of debt relief.

Does high government debt matter?

Experts have different opinions on how much government debt is too much, and debt-to-GDP ratios alone do not determine a country’s risk level. Japan and the U.S., for instance, have among the highest government debt-to-GDP ratios in the world, but credit ratings agencies give both nations generally high marks. These assessments reflect factors other than just government debt, including the country’s capacity and willingness to repay obligations.

In the U.S., a recently enacted $2 trillion relief plan is expected to drive up debt sharply, especially as GDP shrinks. In the first quarter of 2020, the U.S. economy contracted 4.8%, its largest drop-off since the Great Recession – with more of a decline expected in the second quarter. The Congressional Budget Office projected on April 28 that without policy changes, the federal debt-to-GDP ratio could rise to its highest level ever by the end of the 2021 fiscal year.

At the same time, the relief plan is also likely to help stave off worse economic conditions, and because interest rates are low, borrowing is cheaper than it might otherwise be.

In an April Pew Research Center survey, 88% of U.S. adults said the economic aid plan was the “right thing to do,” with majorities saying it will provide a great deal or fair amount of help to large businesses (77%), small businesses (71%), unemployed people (68%) and state and local governments (67%).

Meanwhile, few Americans see government debt as a pressing problem, even as the total federal debt now exceeds $24 trillion. In Gallup surveys earlier this year and last year, only a small fraction of U.S. adults (1% in an April survey) identified the federal budget deficit and federal debt as the most important problem facing the country today. And Pew Research Center surveys have found a decline since 2013 in the share of U.S. adults who say reducing the federal budget deficit should be a top priority for the president and Congress. (The Center’s surveys ask about the budget deficit rather than the debt.)