The number of Americans who have filed first-time claims for unemployment benefits has blown past previous records – more than 24 million have filed since mid-March, when the COVID-19 pandemic began shuttering large swaths of the U.S. economy. That figure includes self-employed people, “gig economy” workers and others who until now haven’t been eligible for benefits. (The new Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security, or CARES, Act expanded eligibility and authorized extra benefits for idled workers.)

Despite some broad federal guidelines, claimants still face a hodgepodge of different state rules governing how they can qualify for benefits, how much they’ll get and how long they can collect them – because the United States does not have a single nationwide system for getting cash to jobless workers. Instead, it effectively has 53 separate systems run by the states (plus the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands), which are overseen but not controlled by the federal government.

To provide a picture of unemployment benefits across the United States, as claims spiked due to the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on the economy, we drew from several data sources. Data on “continued weeks claimed,” a measure of how many people claim unemployment benefits in a given week, came from the U.S. Labor Department’s Employment & Training Administration (ETA); unemployment data came from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. We calculated states’ recipiency rates by taking the continued-claims figures for the same week as the reference week for the BLS’s household survey, then dividing it by the total unemployment figure.

Figures for each state’s minimum and maximum weekly benefit amounts, and the maximum duration of benefits, were taken first from the ETA publication “Comparison of State Unemployment Laws 2019.” They were then cross-checked, where possible, against each state unemployment agency’s website and modified if necessary. Information on states’ differing eligibility rules also was taken from the ETA publication.

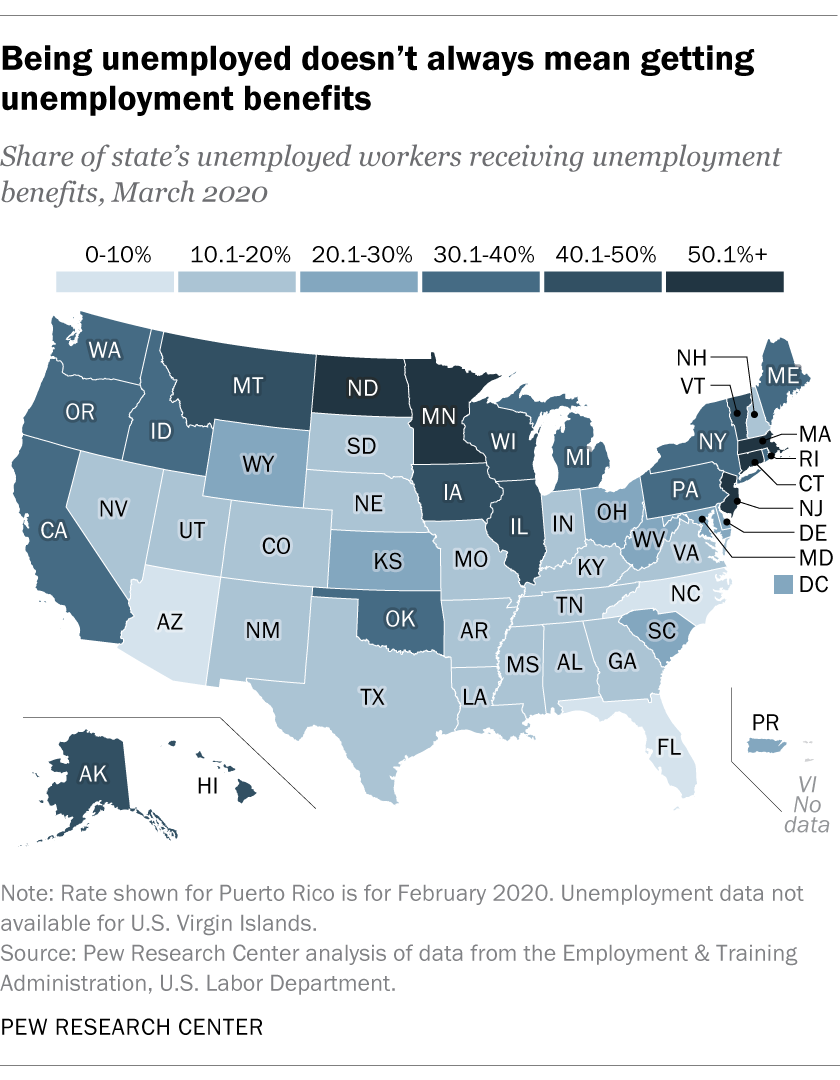

Largely because state rules vary so much, the share of people the government counts as unemployed who actually receive unemployment benefits varies too. In March, just before the pandemic really began wreaking havoc on the economy, 65.9% of unemployed Massachusetts residents received benefit payments but only 7.6% of jobless Floridians did, according to Pew Research Center’s analysis of data from the Labor Department’s Employment & Training Administration and the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Largely because state rules vary so much, the share of people the government counts as unemployed who actually receive unemployment benefits varies too. In March, just before the pandemic really began wreaking havoc on the economy, 65.9% of unemployed Massachusetts residents received benefit payments but only 7.6% of jobless Floridians did, according to Pew Research Center’s analysis of data from the Labor Department’s Employment & Training Administration and the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Overall, about 29% of unemployed Americans, or 2.1 million out of 7.37 million, received benefits in March, according to our analysis. The vast majority of those 2.1 million got their payments through states’ regular unemployment insurance programs. There also are special programs for former federal workers, recently retired military personnel and people whose hours have been cut as part of “work sharing” initiatives.

The disconnect between the official unemployment figures and the number of benefit recipients underscores an often-overlooked fact: Being counted as unemployed and receiving unemployment benefits are two completely different things, and one doesn’t necessarily have much to do with the other. In both cases, not working is a necessary condition but not the only one.

The government’s official unemployment data is derived from the monthly Current Population Survey. To be counted as unemployed, you have to be out of a paying job during the survey’s reference week (March 8-14 in this case) but be available for work and have actively looked for it sometime in the past four weeks. (Workers who have been laid off but expect to be recalled also are counted as unemployed. The number of people in that category more than doubled in March, to a seasonally unadjusted 2.2 million.)

To collect unemployment benefits, you have to be out of work “through no fault of your own,” meaning that people who quit or are fired for cause generally can’t collect. But that’s just one condition among many.

For one thing, you have to earn a minimum amount of wage income to qualify. That amount varies from state to state, as does the way it’s calculated and the time period within which it must be earned. Many states make applicants wait a week before collecting their first benefit check (though some states have waived that requirement for the duration of the current crisis). Some specific categories of workers may not be eligible at all: Real estate agents paid on commission, for example, can collect benefits in only six states. On the other hand, in 28 states workers who are still employed but have had their hours reduced can collect partial benefits through “short-term compensation” (or “work sharing”) programs.

Also, since claimants can only collect benefits for a limited time, a lengthy spell of unemployment can cause them to exhaust their benefits – another way in which people can be out of work and yet not eligible for unemployment compensation. In times of economic crisis, though, federal and state laws often authorize extended benefits: The CARES Act, for instance, allows states to provide up to 13 additional weeks of federally funded benefits to people who have exhausted their regular state benefits.

All of those factors contribute to states’ varying rates of benefit recipiency. Nonetheless, some regional patterns stand out. Of the 10 states where fewer than 15% of unemployed people received benefits in March, seven were in the South, while nine of the 12 states where over 40% of jobless people collected benefits in March were in the Northeast or Midwest.  (Recipiency rates fell in all but nine states between February and March, reflecting the sharp increase in unemployment and the lag time between losing one’s job and first collecting benefits.)

(Recipiency rates fell in all but nine states between February and March, reflecting the sharp increase in unemployment and the lag time between losing one’s job and first collecting benefits.)

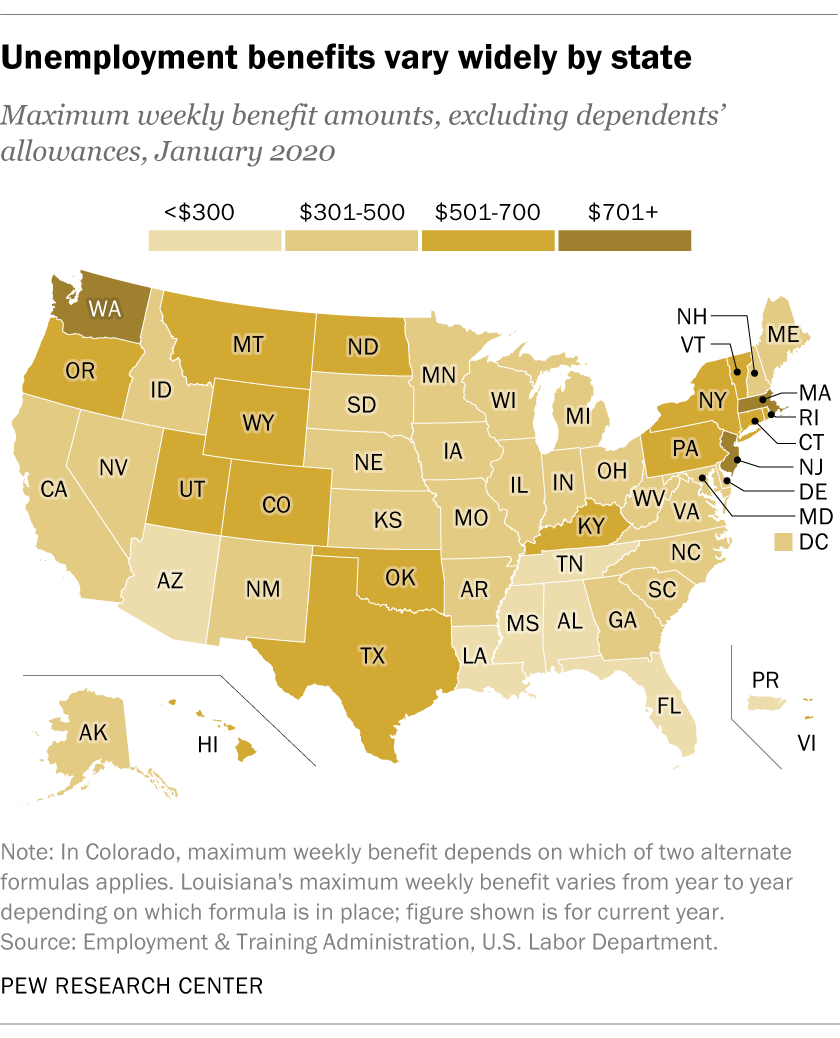

States and territories typically calculate a person’s weekly benefit amount as some percentage of their pre-unemployment earnings, but those benefits are capped. The caps vary widely too, from $823 a week in Massachusetts to $235 a week in Mississippi and $190 a week in Puerto Rico. (Some states give extra benefits for dependent children and other family members, each according to their own rules and restrictions.)

Regional differences also show up in maximum benefit amounts: Seven of the 10 states with the lowest maximum weekly benefits ($350 or less) are in the Southeast,  while nearly all the states with the 10 highest maximums are in the Northeast or along the nation’s northern tier.

while nearly all the states with the 10 highest maximums are in the Northeast or along the nation’s northern tier.

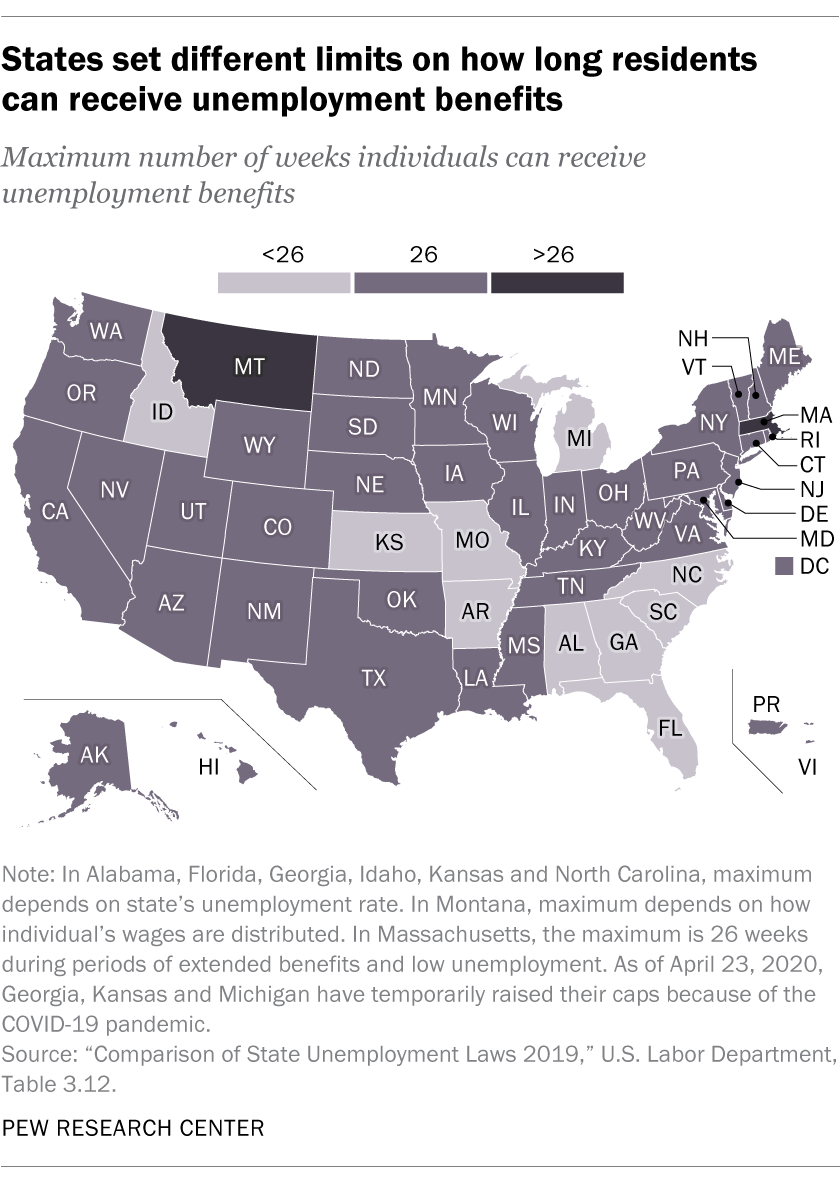

There’s less variation in how long people can collect benefits. Before COVID-19 began ravaging the economy, most states had set their standard duration of benefits at 26 weeks; 10 states (six of them in the South) had shorter limits, while two had longer ones (Montana at 28 weeks, and Massachusetts at 30 under certain conditions). Since the start of the pandemic, three states (Georgia, Kansas and Michigan) have temporarily raised their caps to 26 weeks.

Note: The chart “States set different limits on how long residents can receive unemployment benefits” was updated April 27, 2020, to more accurately reflect unemployment laws in Kansas and Idaho prior to changes resulting from the COVID-19 outbreak.