Hospitals have had to make difficult decisions as the COVID-19 pandemic unfolds. In the U.S. and elsewhere, questions at the intersection of medicine and morality have arisen, such as who should receive critical care if medical resources are in short supply.

Among the dilemmas that came up as the U.S. raced to increase its supply of ventilators was the question of who should be given priority if some hospitals do not have enough ventilators for all patients who need help breathing. Should it be patients who need the ventilators most at the time, even if that means more lives overall are lost? Or patients with the highest chance of recovery, even if that means some people are denied potentially life-saving care based on their age or health status?

Religion is thought to play a role in ethical decision making, and to better understand this relationship, we analyzed responses about resource allocation during the COVID-19 pandemic that were asked in a Pew Research Center survey of 4,917 U.S. adults in April 2020. Everyone who took part is a member of Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology.

Here are the questions used for this report, along with responses, and its methodology.

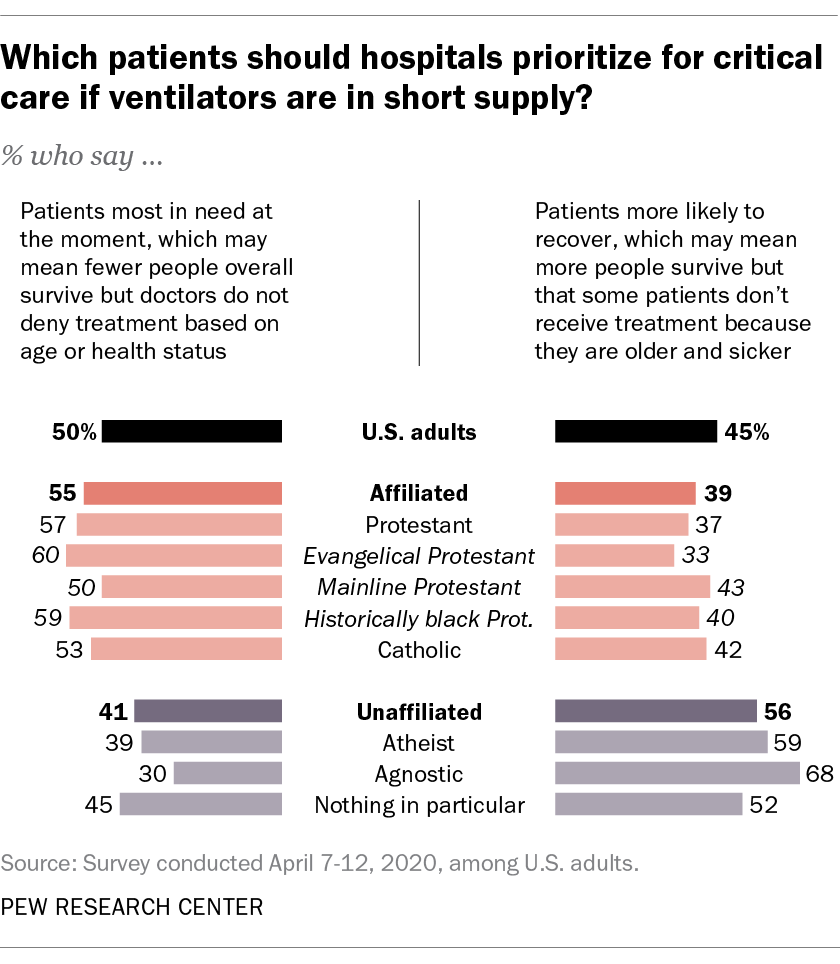

Americans are split on this question, according to a recent Pew Research Center survey. And there are stark differences in opinion based on respondents’ religious affiliation and how religious they are.

Most noteworthy, people with no religious affiliation are the only group with a majority (56%) saying that ventilators should be saved for those with the highest chance of recovery in the event that there are not enough resources to go around, even if that means some patients don’t receive the same aggressive treatment because they are older, sicker and less likely to survive. This view aligns with medical guidelines that typically call for a utilitarian approach — one that prioritizes good outcomes for the greatest number of people.

Most noteworthy, people with no religious affiliation are the only group with a majority (56%) saying that ventilators should be saved for those with the highest chance of recovery in the event that there are not enough resources to go around, even if that means some patients don’t receive the same aggressive treatment because they are older, sicker and less likely to survive. This view aligns with medical guidelines that typically call for a utilitarian approach — one that prioritizes good outcomes for the greatest number of people.

Only a minority of the religiously unaffiliated overall (though a sizable one at 41%) say ventilators should go to those who need them most at the moment the decision is being made.

These findings are consistent with research showing that people who are not religious tend to prefer utilitarian solutions in a variety of moral dilemmas. This may in part be due to a lack of shared, formalized moral rules among the nonreligious, who are more likely to rely on personal philosophy and ethical principles when resolving moral quandaries. Religious believers, on the other hand, often rely on deeply ingrained moral rules and on guidance from religious leaders and texts. Religious people also may respond negatively to the idea of doctors “playing God” by choosing which patients should receive potentially life-saving treatments.

Indeed, most of the religiously affiliated groups covered in this analysis say ventilators in short supply should go to patients who need them most in the moment, which might mean that fewer people survive but no one is denied treatment based on their age or health status. This view is shared by roughly six-in-ten of both evangelicals (60%) and Protestants from historically black churches (59%). Only one-third of evangelicals believe that priority should be given to those who are most likely to survive with aggressive treatment.

Indeed, most of the religiously affiliated groups covered in this analysis say ventilators in short supply should go to patients who need them most in the moment, which might mean that fewer people survive but no one is denied treatment based on their age or health status. This view is shared by roughly six-in-ten of both evangelicals (60%) and Protestants from historically black churches (59%). Only one-third of evangelicals believe that priority should be given to those who are most likely to survive with aggressive treatment.

Catholics aren’t as united in their response, but they also are more likely to say that ventilators should be used on people most in need rather than those most likely to recover. Opinions among mainline Protestants are roughly evenly divided.

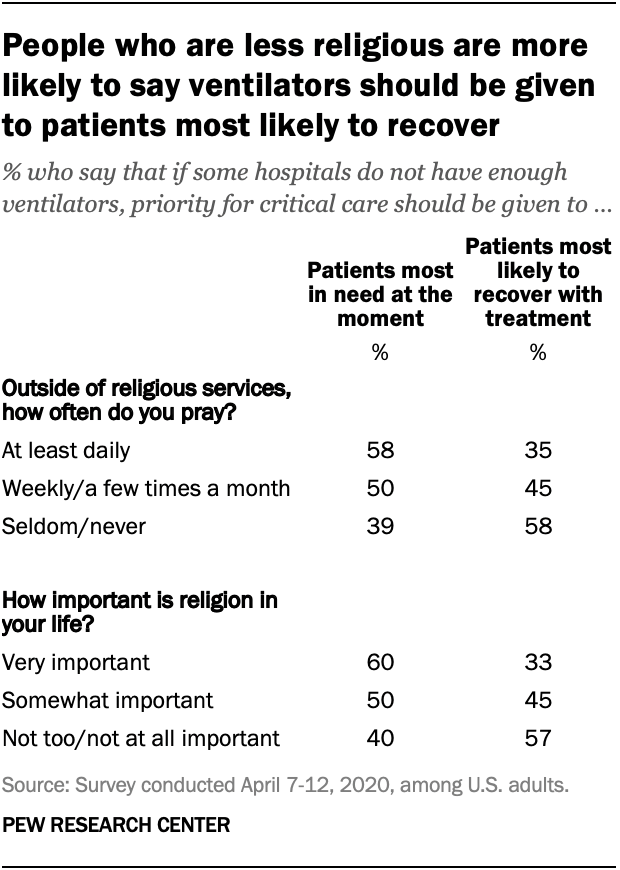

Whether a person is very religious or not, as defined by two standard measures of belief and practice, also is tied to views on this question: Regardless of their affiliation, people who pray more often and who say religion is more important in their life are more likely to prioritize giving ventilators to those most in need at that given moment, rather than to those who have the best chance of surviving.

Among people who pray at least once a day, 58% say ventilators should be given to patients who need them most in the moment, compared with half of those who pray several times per month and 39% of people who seldom or never pray.

The same pattern applies to the measure of religious importance. A majority of people who say religion is “very important” in their life support giving ventilators to patients who need them most in the moment, compared with a minority of those for whom religion is “not too” or “not at all important.”

Note: Here are the questions used for this report, along with responses, and its methodology.