The spread of the new coronavirus in the United States comes at a time of low public trust in key institutions. Only around a third of U.S. adults (35%) have a great deal or a fair amount of confidence in elected officials to act in the public’s best interests, and fewer than half say the same about business leaders (46%) and the news media (47%), according to a January 2019 Pew Research Center survey.

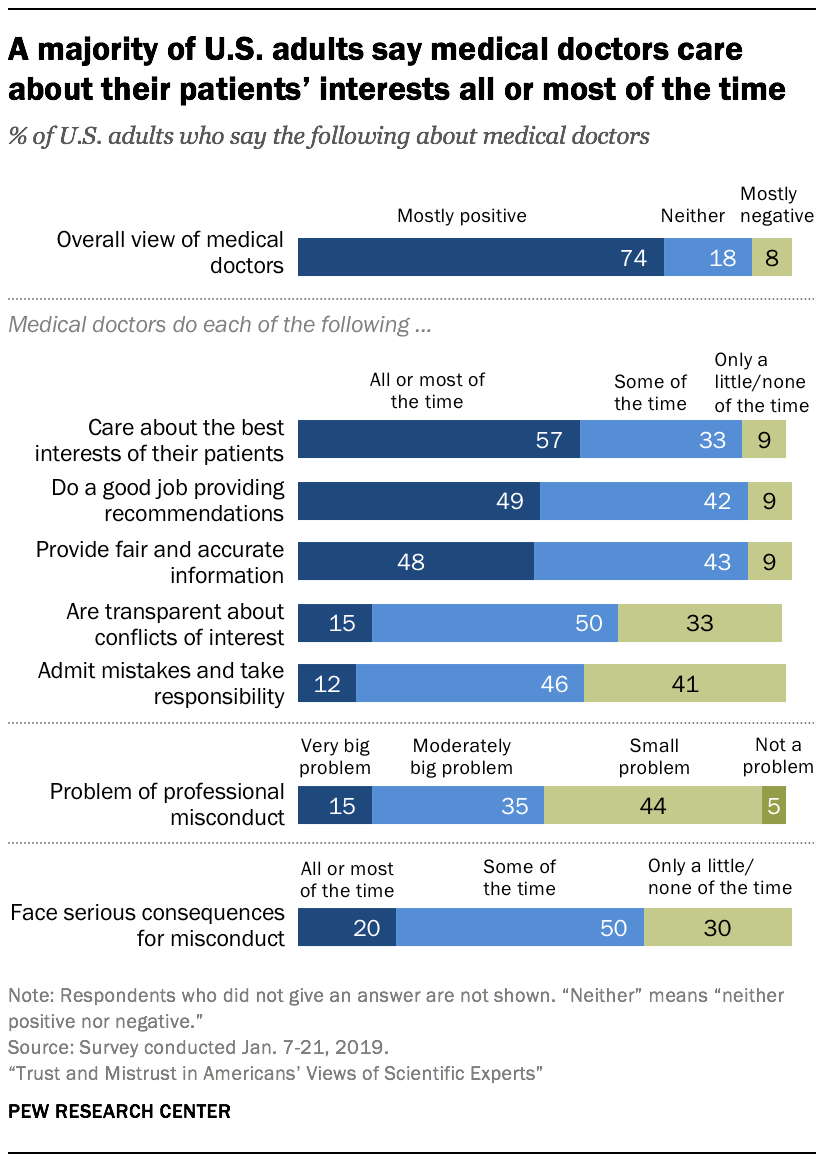

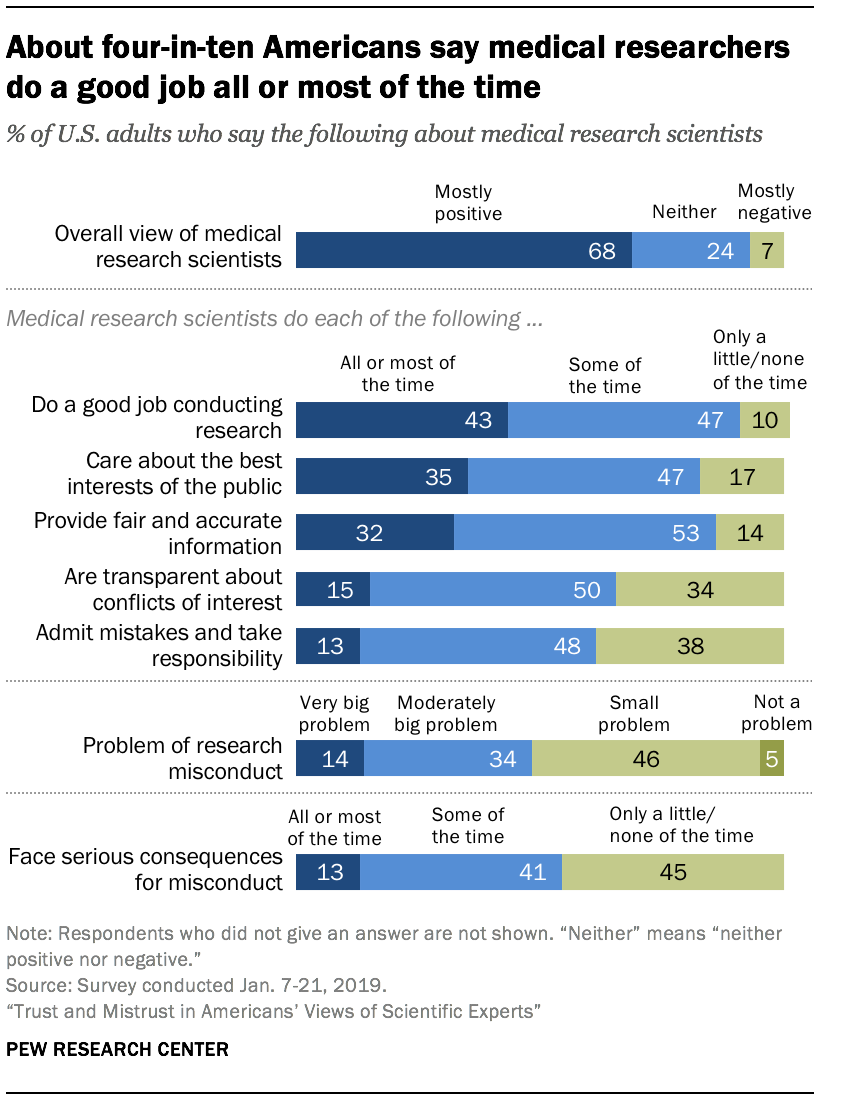

Public attitudes are substantially more positive when it comes to another set of participants in the unfolding coronavirus threat: doctors and medical research scientists. In the same survey, 74% of Americans said they had a mostly positive view of medical doctors, while 68% had a mostly favorable view of medical research scientists – defined as those who “conduct research to investigate human diseases and test methods to prevent and treat them.”

Public attitudes are substantially more positive when it comes to another set of participants in the unfolding coronavirus threat: doctors and medical research scientists. In the same survey, 74% of Americans said they had a mostly positive view of medical doctors, while 68% had a mostly favorable view of medical research scientists – defined as those who “conduct research to investigate human diseases and test methods to prevent and treat them.”

The public gave doctors high marks on several specific aspects of trust. Around half of Americans or more said medical doctors always or usually care about their patients’ best interests (57%), do a good job providing diagnoses and treatment recommendations (49%) and provide fair and accurate information when making recommendations (48%). But notably smaller shares said doctors are transparent about potential conflicts of interest with industry groups (15%) and admit mistakes and take responsibility all or most of the time (12%).

With the coronavirus disease known as COVID-19 raising health concerns worldwide, we wrote this analysis about Americans’ attitudes toward doctors and medical research scientists based on a survey of 4,464 U.S. adults conducted Jan. 7-21, 2019, and a separate survey of 1,549 U.S. adults conducted May 10-June 6, 2016. Everyone who took part in the two surveys is a member of Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The surveys are weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology.

Here are the questions used in this analysis, along with responses, and the methodology.

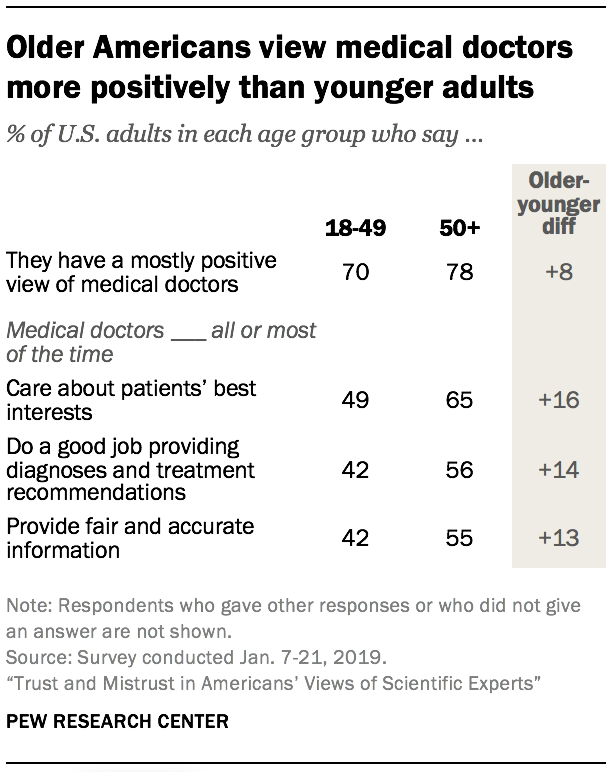

The coronavirus outbreak has hit older people especially hard. In the Center’s survey, older Americans were more likely than younger adults to express trust in doctors, both generally and in more specific terms. Those ages 50 and older, for example, were more likely than adults under 50 to say medical doctors usually do a good job providing diagnoses and treatment recommendations (56% vs. 42%) and that doctors care about their patients’ best interests all or most of the time (65% vs. 49%).

There were no significant partisan differences in views of doctors: Around three-quarters of both Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents (73%) as well as Republicans and GOP leaners (77%) expressed a mostly positive opinion of medical doctors. This differs notably from the public’s evaluations of other societal institutions, especially the news media, where attitudes are deeply polarized along partisan lines.

There were no significant partisan differences in views of doctors: Around three-quarters of both Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents (73%) as well as Republicans and GOP leaners (77%) expressed a mostly positive opinion of medical doctors. This differs notably from the public’s evaluations of other societal institutions, especially the news media, where attitudes are deeply polarized along partisan lines.

The public is broadly familiar with the work that doctors do, which may help explain its positive opinions of them. The vast majority of Americans said in the same 2019 survey that they know either a lot (46%) or a little (48%) about what medical doctors do. Across a variety of scientific professions asked about in the survey – from dietitians to environmental researchers – higher levels of familiarity were associated with more positive and more trusting views of the professionals in question.

Compared with doctors, Americans are less familiar with the work of medical research scientists. Just 16% said they know a lot about what these researchers do, while two-thirds (67%) said they know a little about it and 17% said they know nothing about what this group does.

Compared with doctors, Americans are less familiar with the work of medical research scientists. Just 16% said they know a lot about what these researchers do, while two-thirds (67%) said they know a little about it and 17% said they know nothing about what this group does.

Medical research scientists also draw comparatively less confidence than doctors on a variety of specific questions about their work. Only around a third of the public, for instance, said these researchers always or usually care about the best interests of the public (35%) and provide fair and accurate information (32%).

Older people were more likely than younger people to express a positive view of medical research scientists, as was the case for doctors, but the differences were modest. There were again no significant differences in views between Democrats and Republicans.

Personal experiences with health care providers

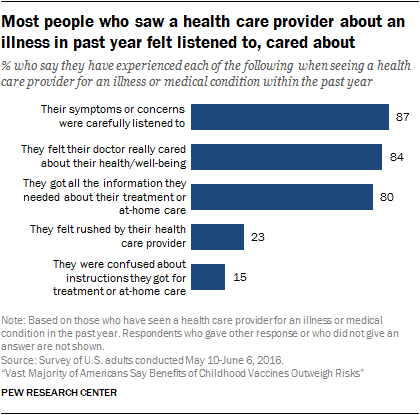

The Center’s 2019 survey asked Americans about doctors as a group, rather than the individual doctors who patients may have gone to see. But another Pew Research Center survey conducted in the spring of 2016 asked Americans about more direct experiences with their health care providers. It, too, revealed mostly positive opinions.

The Center’s 2019 survey asked Americans about doctors as a group, rather than the individual doctors who patients may have gone to see. But another Pew Research Center survey conducted in the spring of 2016 asked Americans about more direct experiences with their health care providers. It, too, revealed mostly positive opinions.

In that survey, 63% of U.S. adults said they had seen a health care provider for an illness or medical condition within the past year. Among those, eight-in-ten or more said their symptoms or concerns were carefully listened to (87%), their doctor really cared about their health and well-being (84%), and they got all the information they needed about their treatment or at-home care (80%). Only around a quarter of Americans (23%) said they felt rushed by their health care provider, and even fewer (15%) said they were confused about the instructions they got for their treatment or other home care.

Note: Here are the questions used in this analysis, along with responses, and the methodology.