Immigrants remain more likely than U.S.-born workers to work in lower-skill occupations. But the share of immigrants in high-skill, nonmechanical jobs has risen in recent decades, according to a new Pew Research Center analysis of federal government data. The shift has been most notable in jobs that prioritize analytical skills, such as science and math, or fundamental skills, such as writing and speaking. A rising share of immigrants also work in jobs in which social skills like negotiation and persuasion are important.

Immigrants remain more likely than U.S.-born workers to work in lower-skill occupations. But the share of immigrants in high-skill, nonmechanical jobs has risen in recent decades, according to a new Pew Research Center analysis of federal government data. The shift has been most notable in jobs that prioritize analytical skills, such as science and math, or fundamental skills, such as writing and speaking. A rising share of immigrants also work in jobs in which social skills like negotiation and persuasion are important.

Within this broad overall pattern, there are key differences between immigrant groups. Hispanic immigrants – by far the largest group of immigrant workers – are for the most part employed in lower-skill occupations. Asian immigrants – the largest bloc of new arrivals – work principally in higher-skill occupations. The distribution of skills among black immigrants falls between these two extremes, whereas white immigrant workers are spread across high-skill jobs like their Asian counterparts.

Overall, the share of immigrants in the U.S. labor force has increased sharply in recent decades, from 10% in 1995 to 17% in 2018. Immigrants are also expected to play the primary role in the growth of the country’s workforce through 2035.

The American workplace has seen a rising need for high-skill workers in recent decades. This analysis examines how different groups of immigrant workers have increasingly fulfilled this demand, yet still trail behind their U.S.-born counterparts.

The numbers reported are derived from job skills and preparation data from the U.S. Department of Labor’s Occupational Information Network (O*NET), specifically Version 23, released August 2018. O*NET analysts rate the importance of 35 skills related to job performance in individual occupations. For the purposes of this analysis, we grouped these into five major families of job skills: social, fundamental, analytical, managerial and mechanical. Occupations were then assigned to one of four skill tiers based on the importance rating of each of the five major skills, ranging from least important to most important.

For additional details on the data sources used and how the analysis was conducted, see the boxes within this post and the full methodology from a related Pew Research Center report released in January.

Immigrants more likely than U.S.-born workers to work in lower-skill jobs

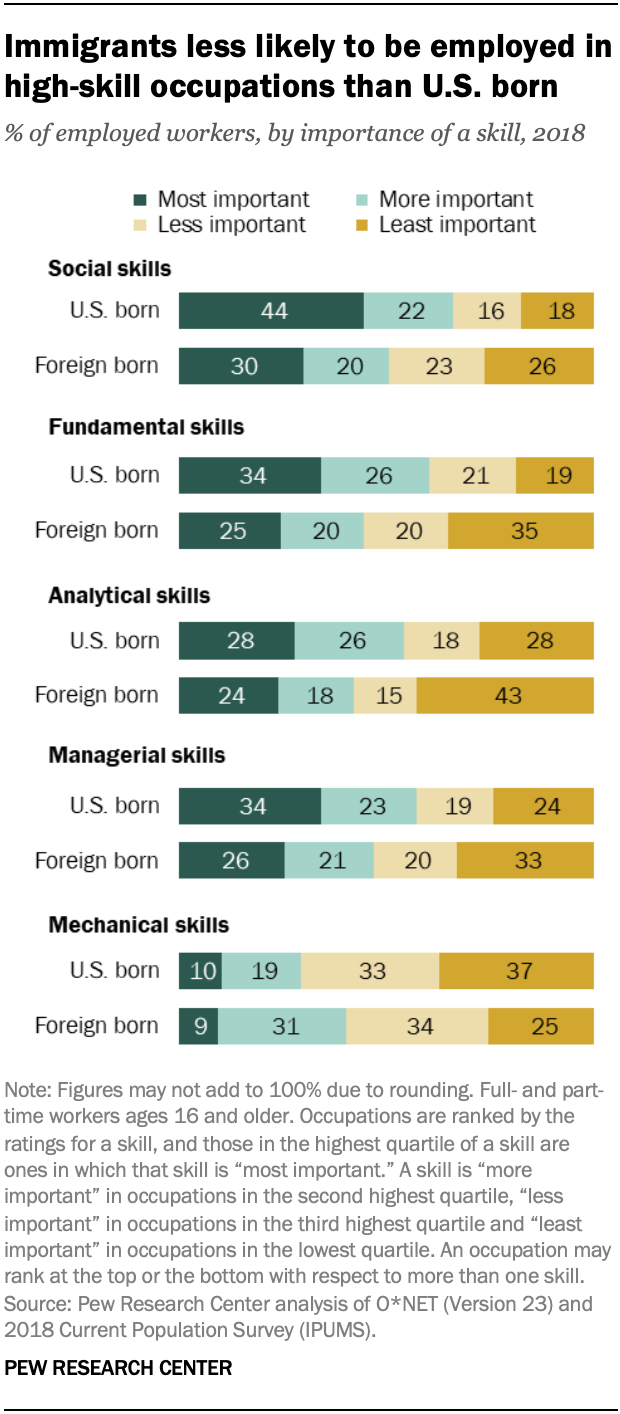

Immigrants and U.S.-born workers differ when it comes to the skills their jobs prioritize. Immigrants are less likely to work in jobs placing a higher degree of importance on nonmechanical skills – specifically social, fundamental, analytical or managerial skills. (See the accompanying text box for the definitions of these skills.)

The U.S. Department of Labor’s Occupational Information Network (O*NET), a government database of occupational information, provides ratings on the importance of 35 detailed job skills. We grouped these skills into five major families of job skills as follows:

Social skills – instructing, service orientation, monitoring, social perceptiveness, coordination, negotiation and persuasion

Fundamental skills – critical thinking, writing, speaking, reading comprehension, active listening, active learning, learning strategies, and judgment and decision-making

Analytical skills – science, mathematics, programming, complex problem solving, systems analysis, systems evaluation, operations analysis and technology design

Managerial skills – management of personnel resources, management of financial resources, management of material resources and time management

Mechanical skills – troubleshooting, equipment selection, equipment maintenance, repairing, installation, operation monitoring, quality control analysis and operation and control

This analysis divides occupations into four skill tiers based on the importance rating of each of the five skill groups. Occupations are ranked by their importance rating on, say, social skills, and the top 25% of occupations (the highest quartile) are listed as “most important” users of social skills. The second and third quartile of occupations are defined to be “more important” and “less important” users of social skills, respectively. Finally, the bottom 25% of occupations (the lowest quartile) are listed as “least important” users of social skills. This process is repeated for each of the five major skill groups.

Examples of occupations with among the greatest need for these skill groups are as follows:

Social skills – Sales managers, coaches and scouts, marriage and family therapists

Fundamental skills – Lawyers, psychiatrists, education administrators

Analytical skills – Physicists, biomedical engineers, computer and information research scientists

Managerial skills – Chief executives, construction managers, medical and health services managers

Mechanical skills – Signal and track switch repairers, industrial machinery mechanics, millwrights

In 2018, fewer than a third of foreign-born workers (30%) were employed in occupations where social skills are “most important,” such as registered nurses and social service managers, compared with 44% of U.S.-born workers. The same pattern emerges for occupations in which fundamental skills are most important, like elementary school teachers and lawyers. Just one-in-four foreign-born workers were employed in these occupations in 2018, compared with about a third of U.S.-born workers (34%).

On the other hand, immigrants were more likely than U.S.-born workers to be employed in lower-skill jobs. In 2018, 43% of immigrant workers worked in jobs in which analytical skills are “least important,” compared with only 28% of U.S.-born workers. Similarly, 35% of immigrants were employed in jobs in which fundamental skills are least important, compared with 19% of U.S.-born workers. Examples of these jobs include welders and loading machine operators.

The roles of immigrant and U.S.-born workers are reversed with respect to mechanical skills. In 2018, immigrants were more likely than U.S.-born workers to be employed in occupations where mechanical skills are “most” or “more important” (40% vs. 29%). These include jobs such as industrial machinery mechanics and electricians, which call for skills such as repairing and installation. But jobs calling for high-order mechanical skills are not necessarily high-wage jobs. The average wage in these jobs is well below the average wage in jobs in which social, fundamental, analytical or managerial skills are most important, as noted in a recent Pew Research Center report.

The share of immigrant workers in higher-skill jobs is rising

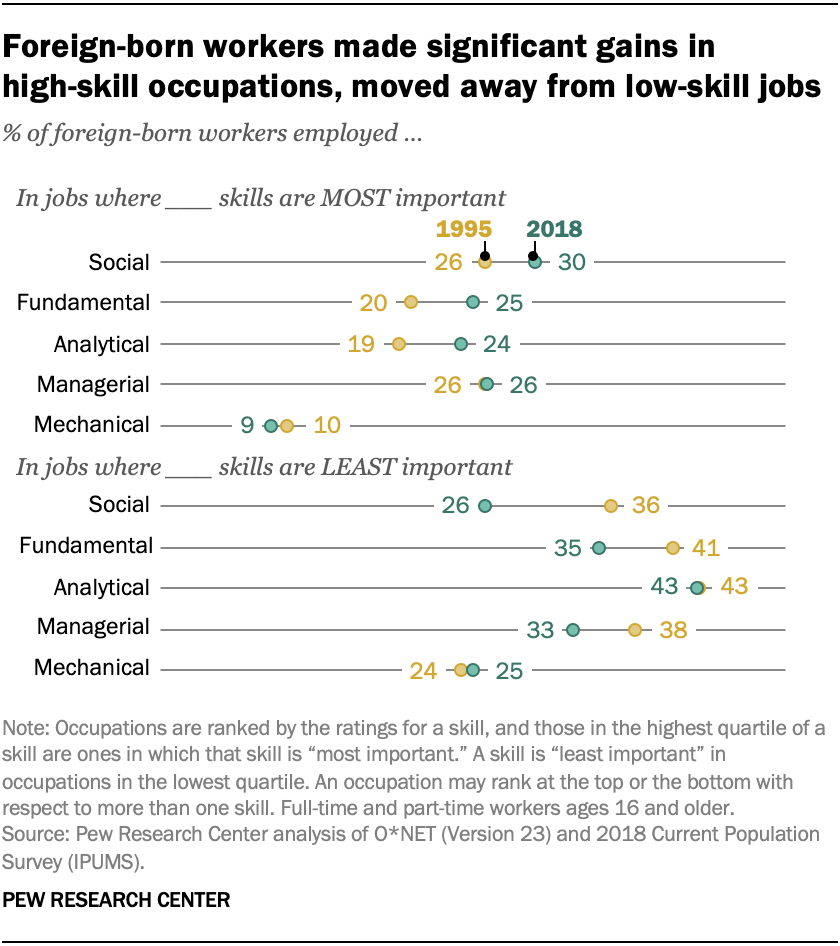

Although immigrants overall are still more concentrated in lower-skill jobs than U.S.-born workers, they have experienced employment growth in many high-skill occupations since 1995. The share of foreign-born workers employed in occupations where fundamental skills are most important increased from 20% in 1995 to 25% in 2018. Over the same period, the share of foreign-born workers in jobs most in need of social skills increased from 26% to 30%, and the share in high-analytical-skill jobs (such as biomedical engineers) increased from 19% to 24%. These changes have come amid a rising demand for skilled workers in the U.S. labor market overall.

Although immigrants overall are still more concentrated in lower-skill jobs than U.S.-born workers, they have experienced employment growth in many high-skill occupations since 1995. The share of foreign-born workers employed in occupations where fundamental skills are most important increased from 20% in 1995 to 25% in 2018. Over the same period, the share of foreign-born workers in jobs most in need of social skills increased from 26% to 30%, and the share in high-analytical-skill jobs (such as biomedical engineers) increased from 19% to 24%. These changes have come amid a rising demand for skilled workers in the U.S. labor market overall.

As more immigrant workers transitioned into high-skill occupations, there have been simultaneous decreases in the share of foreign-born workers employed in occupations where social or fundamental skills are least important, such as dishwashers and crossing guards. For example, the share of foreign-born workers employed in occupations where social skills are least important decreased from 36% in 1995 to 26% in 2018.

This move toward high-skill occupations is due in part to a rising level of education among immigrants overall. In 2018, 34% of immigrants ages 25 and older had a bachelor’s degree or more education, up from 22% in 1995. One contributing factor was a surge in the arrival of highly educated Asian immigrants during the 2000s, driven by the expansion of the H-1B visa program since the 1990s.

Immigrant groups differ in their likelihood of working in high-skill jobs

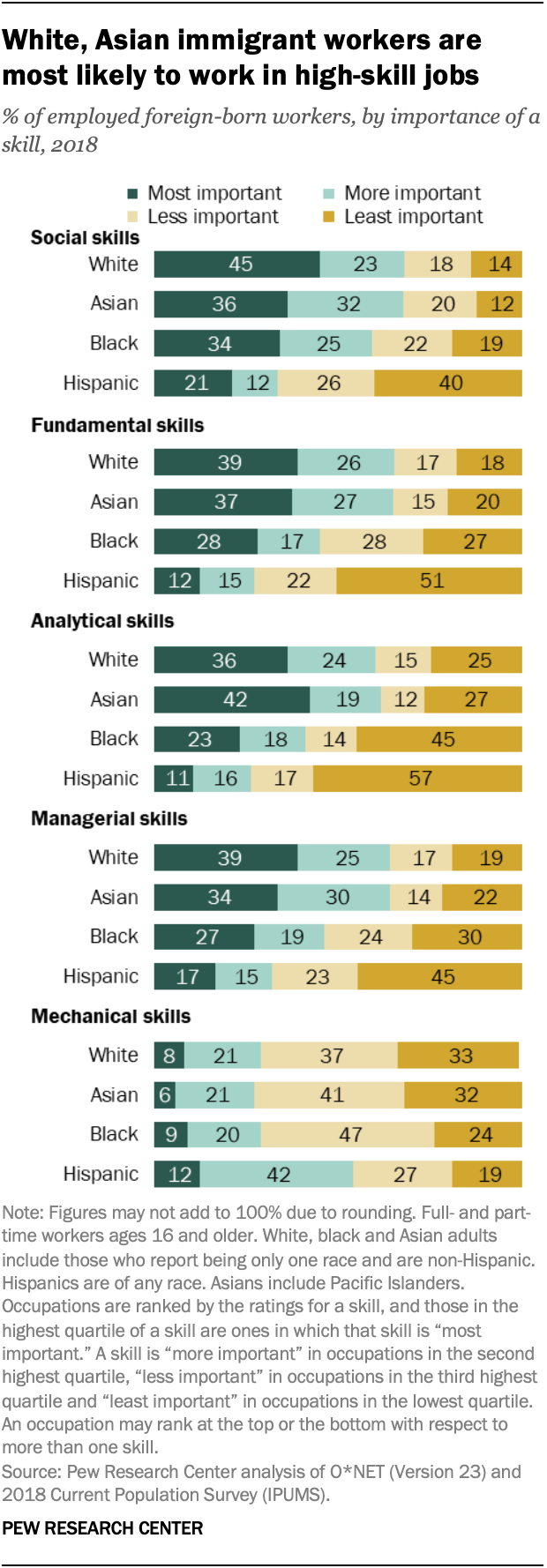

In 2018, Asian and white immigrants were much more likely than Hispanic and black immigrants to work in nonmechanical, high-skill occupations. For example, 42% of Asian immigrants and 36% of white immigrants worked in jobs where analytical skills are most important, such as chemical engineers and computer programmers, compared with 23% of black immigrants and just 11% of Hispanic immigrants. There were similar differences in jobs in which fundamental and managerial skills are most important. White immigrants were more likely than those in other groups to work in jobs prioritizing social skills.

In 2018, Asian and white immigrants were much more likely than Hispanic and black immigrants to work in nonmechanical, high-skill occupations. For example, 42% of Asian immigrants and 36% of white immigrants worked in jobs where analytical skills are most important, such as chemical engineers and computer programmers, compared with 23% of black immigrants and just 11% of Hispanic immigrants. There were similar differences in jobs in which fundamental and managerial skills are most important. White immigrants were more likely than those in other groups to work in jobs prioritizing social skills.

Black immigrants, while lagging behind their white and Asian counterparts in high-skill jobs, were still more likely to be employed in these occupations than Hispanics. About one-in-five or more black immigrants were employed in high-analytical and high-fundamental-skill occupations, about double the share of Hispanic immigrants in similar jobs. Sizable gaps also existed between the representation of black and Hispanic immigrants in jobs in which social and managerial are most important.

Hispanic immigrants are most likely to be employed in lower-skill nonmechanical occupations. In 2018, the majority of Hispanic immigrants worked in occupations where analytical (57%) and fundamental (51%) skills are least important, and four-in-ten or more worked in occupations in which social or managerial skills are least important. These shares were significantly higher than those among other immigrant groups. For example, about one-in-five or fewer black, white and Asian immigrants were employed in occupations where social skills were least important.

At the same time, Hispanic immigrants are more likely than other immigrant workers to be employed in occupations requiring greater proficiency in mechanical skills, like elevator installers and repairers. In 2018, more than half of foreign-born Hispanic workers (54%) were employed in occupations where mechanical skills are most or more important, compared with about three-in-ten or fewer among Asian, black or white immigrants.

Despite the skill differences between immigrants of different races and ethnicities, all four groups have moved toward high-skill occupations and away from low-skill occupations over the past two decades. For example, only three-in-ten Asian immigrants worked in occupations where analytical skills are most important in 1995. By 2018, this share increased to 42%. And nearly four-in-ten white immigrants (36%) were employed in these occupations in 2018, up from three-in-ten in 1995.

Among foreign-born Hispanic workers, the share employed in occupations where social skills are most important increased from 16% in 1995 to 21% in 2018. Hispanic immigrant workers also moved away from bottom-tier social-skill occupations, with their share in these jobs falling from 51% in 1995 to 40% in 2018.

Like Hispanic immigrant workers, the share of black immigrants in high-social skill occupations has also gone up. The share of black immigrant workers in these occupations stood at 34% in 2018, up from 26% in 1995.

The rising share of immigrants in high-skill occupations is partly explained by higher levels of education among all four immigrant groups. In 2018, 55% of white immigrants and 61% of Asian immigrants had a bachelor’s degree or more education, considerably greater than in 1995, when these shares stood at 38% and 45%, respectively. The share of black immigrants with a bachelor’s degree or more increased from 25% in 1995 to 36% in 2018, due in part to highly educated black immigrants moving to the U.S. from Africa.

Among Hispanics, the share of immigrants with a bachelor’s degree or more increased from 8% in 1995 to 15% in 2018. More recently, a decrease in the number of unauthorized workers since 2008 has likely contributed to a shift toward higher-skill occupations among Hispanics. A slowdown in arrivals from Latin America, especially from Mexico, also boosted the number of years the typical Hispanic immigrant has lived in the United States. In 2018, half of Latin American immigrant workers had been living in the U.S. for at least 20 years, compared with 36% in 2008. Research has shown that more time spent in the U.S. generally leads to better opportunities in the labor market.

This analysis is based on the combination of job skills and preparation data from the U.S. Department of Labor’s Occupational Information Network (O*NET) and occupational employment data from the Current Population Survey (CPS).

The O*NET database provides a variety of information related to the requirements of more than 950 occupations. The occupations are classified according to a coding scheme that is consistent with the 2010 Standard Occupational Classification. Among other things, O*NET includes information on 35 specific skills representing attributes of workers related to work performance (critical thinking or service orientation, for example). Each skill is rated on a scale of one to five measuring its importance to job performance, from not important to extremely important. This analysis uses Version 23, released in 2018.

Conducted jointly by the U.S. Census Bureau and the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the CPS is a monthly survey of approximately 55,000 households and is the source of the nation’s official statistics on unemployment. The CPS sample covers the civilian, non-institutionalized population. In this analysis, 12 monthly CPS files in each year were combined to generate annual estimates of occupational employment in 1995 and 2018. The CPS microdata files used in this report are the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS-CPS) provided by the University of Minnesota.

Because O*NET does not contain employment information for occupations, it is necessary to match the skills data to CPS data. Although both the 2018 O*NET and the CPS use the 2010 standard occupational classification there is one key difference: O*NET lists more than 950 occupations coded at the eight-digit level, the finest detail possible, whereas the CPS lists fewer than 500 occupations coded at the four-digit level. In other words, an occupation listed in the CPS typically encompasses more than one occupation listed in O*NET. Thus, occupational data in O*NET must be aggregated to match up to the CPS data. See here for more details on the aggregation methods and matching the two datasets.