Andrew Kohut, the founding director of Pew Research Center and its president from 2004 to 2012, was one of the nation’s leading pollsters. He died in 2015. His work, over three decades, won him wide respect for his expertise and ability to craft stories about what people could learn from survey research. One of his particular talents was to reach back in time to take a snapshot of the mood of Americans in another era to show how much times had changed.

Here is one of those articles, originally published on Feb. 4, 2015, and reflecting the Center’s findings at that time. Italicized notes provide links to our more recent findings.

As Washington once again engages in a heated political battle over immigration policy, it’s worth reminding ourselves just how much the country and its politics have changed since passage of the law that largely created today’s system.

Fifty years ago, the Immigration and Nationality Act dramatically changed the makeup of the country by ending a quota system based on national origins in favor of one that took into account occupational skills, relatives living in the U.S. and political-refugee status.

Despite the long-term impact of the 1965 law and the highly partisan tone the issue has taken on today, immigration was not highly divisive a half-century ago, and the American public paid it little heed. Of course, a lot was going on in 1965 to occupy the public’s attention – Vietnam and civil rights, to name just two mega-issues.

Nonetheless, Gallup polls that year found less than 1% of the public naming immigration as the most important problem facing the nation. And, by the end of 1965, the Harris poll found just 3% naming immigration revision as the legislation most important to them. (Back then, Medicare legislation was cited most often – by 28%.)

While Americans were much quieter about immigration back then, the public was divided about the right level of immigration. A June 1965 Gallup poll found that 39% preferred maintaining present levels, almost as many said they should be decreased (33%), and only a few (7%) favored increased immigration.

But in the end, a majority of the public approved of changing the laws so that people would be admitted on the basis of their occupational skills rather than their country of origin. And after the Immigration and Nationality Act was passed, fully 70% said they favored the new law.

An approval score like that was possible because, unlike today, there were almost no partisan differences on the issue. A mid-1965 Gallup poll found 54% of Republicans and 49% of Democrats favoring the concept of admittance based on job skills. Support was only modestly lower among two population groups: less well-educated Americans (44%) and Southerners (40%).

One can only wonder what reactions would have been had Americans known how much the new law would change the face and complexion of their country in years to come. In 1960, the foreign-born share of the population was just 5%. By 2013, that figure had more than doubled to 13%. (Note: For the latest numbers, see Pew Research Center’s fact sheets on U.S. immigration.)

One can only wonder what reactions would have been had Americans known how much the new law would change the face and complexion of their country in years to come. In 1960, the foreign-born share of the population was just 5%. By 2013, that figure had more than doubled to 13%. (Note: For the latest numbers, see Pew Research Center’s fact sheets on U.S. immigration.)

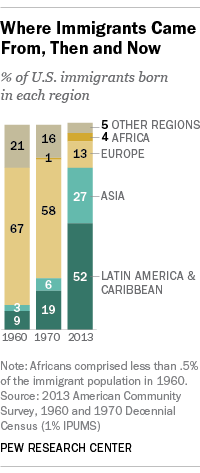

Even more dramatically, the ethnic composition of immigrants has changed. In 1960, the overwhelming share of immigrants were of European origin and few were born in Latin America and the Caribbean or Asia. By 2013, a census survey found half of immigrants were Latin American/Caribbean and 27% were Asian, while the European share of the immigrant population had fallen to a mere 13%.

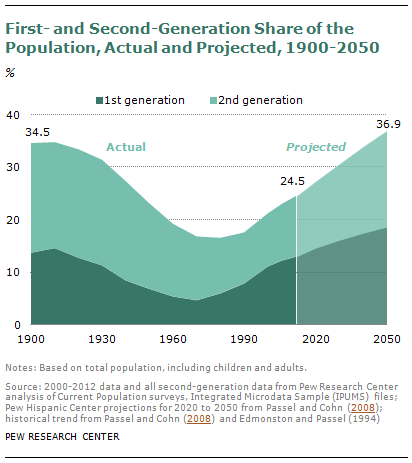

Looking ahead, those changes will become even more pronounced. Based on census data, Pew Research Center projects that the first- and second-generation immigrant segment of the American population will swell to 37% by 2050, compared with 15% back in 1965. This roughly matches the first- and second-generation immigrant percentage of the public at the turn of the 20th century, which was a high point in American immigration. (For updated projections, see the Center’s September 2015 report “Modern Immigration Wave Brings 59 Million to U.S., Driving Population Growth and Change Through 2065.”)

Looking ahead, those changes will become even more pronounced. Based on census data, Pew Research Center projects that the first- and second-generation immigrant segment of the American population will swell to 37% by 2050, compared with 15% back in 1965. This roughly matches the first- and second-generation immigrant percentage of the public at the turn of the 20th century, which was a high point in American immigration. (For updated projections, see the Center’s September 2015 report “Modern Immigration Wave Brings 59 Million to U.S., Driving Population Growth and Change Through 2065.”)

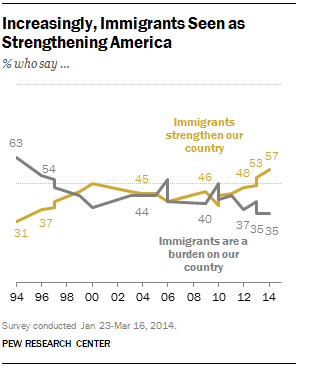

Indeed, immigrants now come from different parts of the world, and they make up a larger share of the American public. This has taken some getting used to on the part of the American public. In the 1990s, by wide margins, Americans saw immigrants as burdens on society rather than as strengthening the country through their hard work. Also, many thought that the growing number of newcomers would threaten traditional American values and customs.

But slowly, opinions have begun to change over the course of the past two decades. By 2014, a healthy 57% majority had come to the opposite point of view, saying that immigrants strengthened the country through their hard work; and just 35% now say that the increasing number of immigrants is threatening American values. (As of January 2019, 62% say immigrants strengthen the country, while 28% say they burden the country by taking jobs, housing and health care.)

But slowly, opinions have begun to change over the course of the past two decades. By 2014, a healthy 57% majority had come to the opposite point of view, saying that immigrants strengthened the country through their hard work; and just 35% now say that the increasing number of immigrants is threatening American values. (As of January 2019, 62% say immigrants strengthen the country, while 28% say they burden the country by taking jobs, housing and health care.)

Given these shifts, it’s not surprising that 50 years after the Immigration and Nationality Act, the public’s bottom line about the law is a thumbs-up. When polled about the desired level of legal immigration, Americans today give a decidedly more positive response than they did back in 1965. Most say either keep immigration at present levels (31%) or increase it (25%), while a minority (36%) say the level of legal immigration should be decreased. (By June 2018, these shares were 38%, 32% and 24%, respectively.)

It is important to recognize that a heated debate about immigration these days, at least from the public’s point of view, is not about the level of immigration, or where people come from, but how to keep out unauthorized immigrants and what to do with those who are now here.

The distinction between how Americans think about legal and illegal immigration is frequently lost in today’s debate. Gallup recently reported that six-in-ten Americans were dissatisfied with “current levels” of immigration. But in its reporting, Gallup went on to point out that its “survey question does not distinguish between legal and illegal immigration.” Even so, a follow-up question found only 39% wanting less immigration – a record low. The polling organization further added that “the rhetoric of many outspoken politicians on this [issue] … often does not distinguish between legal or non-legal status.”