Our approach to generational analysis has evolved to incorporate new considerations. Learn more about how we currently report on generations, and read tips for consuming generations research.

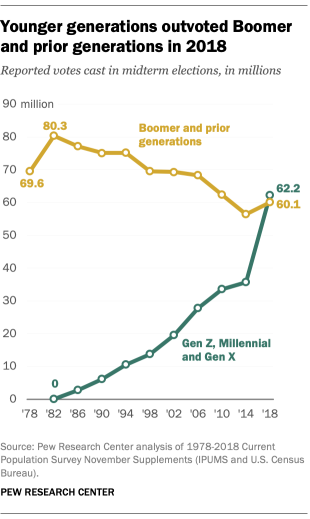

Midterm voter turnout reached a modern high in 2018, and Generation Z, Millennials and Generation X accounted for a narrow majority of those voters, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of newly available Census Bureau data.

The three younger generations – those ages 18 to 53 in 2018 – reported casting 62.2 million votes, compared with 60.1 million cast by Baby Boomers and older generations. It’s not the first time the younger generations outvoted their elders: The same pattern occurred in the 2016 presidential election.

Higher turnout accounted for a significant portion of the increase. Millennials and Gen X together cast 21.9 million more votes in 2018 than in 2014. (The number of eligible voter Millennials and Gen Xers grew by 2.5 million over those four years, due to the number of naturalizations exceeding mortality.) And 4.5 million votes were cast by Gen Z voters, all of whom turned 18 since 2014.

By comparison, the number of votes cast by Boomer and older generations increased 3.6 million. Even this modest increase is noteworthy, since the number of eligible voters among these generations fell by 8.8 million between the elections, largely due to higher mortality among these generations.

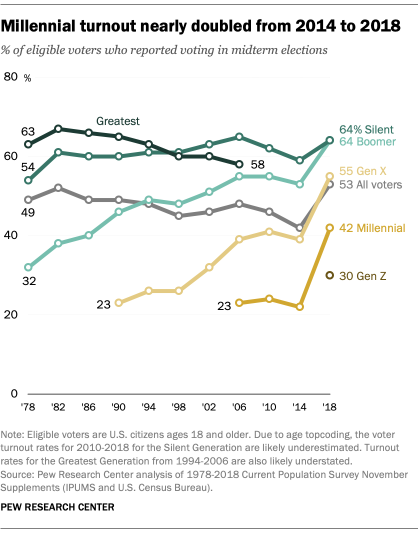

Millennials, Gen Xers and Boomers all set records for turnout in a midterm election in 2018. Turnout rates increased the most for the Millennial generation, roughly doubling between 2014 and 2018 – from 22% to 42%. Among Generation Z, 30% of those eligible to vote (those ages 18 to 21 in this analysis) turned out in the first midterm election of their adult lives. And for the first time in a midterm election, more than half of Gen Xers reported turning out to vote. While turnout tends to increase with age, every age group also voted at higher rates than in 2014, and the increase was more pronounced among younger adults.

The Census Bureau’s biannual Current Population Survey November Voting and Registration Supplement is the best postelection survey of voting behavior available because of its large sample size and its high response rates. It is also one of the few data sources that provides a comprehensive demographic and statistical portrait of U.S. voters.

(Official voting records provide actual individual-level turnout data, but they do not contain voters’ full demographic details. Pew Research Center and other organizations match voter file data to surveys, providing another high-quality source of this information.)

But estimates based on the CPS November Supplement often differ from official voting statistics based on administrative voting records. This difference has been attributed to the way the CPS estimates voter turnout – through self-reports (which may overstate participation) and a method that treats nonresponses from survey respondents as an indication that the survey respondent did not vote (which may or may not be true).

To address overreporting and nonresponse in the CPS, Aram Hur and Christopher Achen in a 2013 paper proposed a weighting method that differs from the one used by the Census Bureau in that it reflects actual state vote counts. As a result, voter turnout rates reported by the Census Bureau (and shown in this analysis) are often higher than estimates based on this alternative weighting approach.

For example, tabulations using this adjustment and reported by Michael McDonald of the University of Florida produce a national voter turnout rate for adults ages 18 to 29 of 32.6% for 2018, 3 percentage points below the figures calculated from Census Bureau’s official estimates of 35.6%.

No matter the method used, voter turnout rates in 2018 were the highest for a midterm election measured using the November Voting and Registration Supplement.

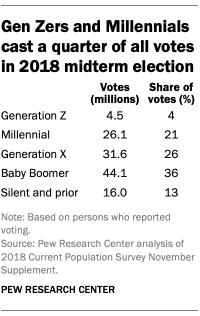

Together, Gen Z and Millennials reported casting 30.6 million votes, a quarter of the total. Gen Z was responsible for 4.5 million, or 4%, of all votes. This post-Millennial generation is just starting to reach voting age, and their impact will likely be felt more in the 2020 presidential election, when they are projected to be 10% of eligible voters.

Millennials, ages 22 to 37 in 2018, cast 26.1 million votes, far higher than the number of votes they cast in 2014 (13.7 million).

Generation X, those ages 38 to 53 in 2018, cast 31.6 million votes – the first time they had more than 30 million votes in a midterm election. Their turnout rate also increased, from 39% in 2014 to 55% four years later.

Baby Boomers, those ages 54 to 72 in 2018, had their highest-ever midterm election turnout (64%, the same rate as the Silent Generation) and cast more votes than they ever have in a midterm (44.1 million). Still, they had a relatively smaller turnout increase than the younger generations (53% of Boomers turned out in 2014). Overall, Boomers cast 36% of ballots in last year’s election – their lowest share of midterm voters since 1986 – because of mortality, while the younger generations are still growing due to naturalizations and adults turning 18.