Public support for the separation of church and state is widespread in Western Europe, even in countries that have a government-mandated church tax to fund religious institutions, according to a new analysis of a recent Pew Research Center study.

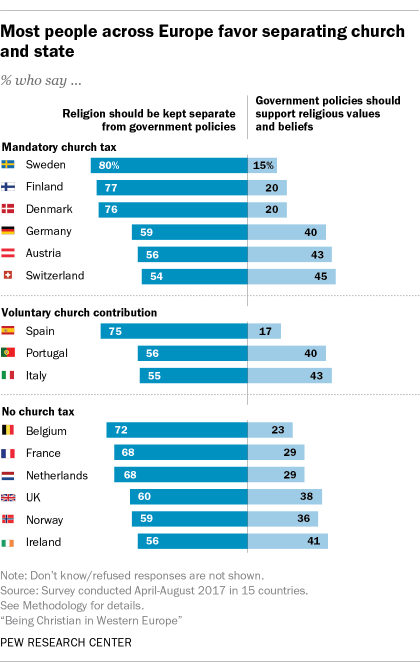

Majorities of adults in six countries with a mandatory church tax for members of major religious groups – Austria, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Sweden and Switzerland – agree with the statement “religion should be kept separate from government policies,” rather than favoring the alternate position that “government should promote religious values and beliefs in the country.” Majorities in several other Western European countries that don’t have a church tax also support church-state separation.

Majorities of adults in six countries with a mandatory church tax for members of major religious groups – Austria, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Sweden and Switzerland – agree with the statement “religion should be kept separate from government policies,” rather than favoring the alternate position that “government should promote religious values and beliefs in the country.” Majorities in several other Western European countries that don’t have a church tax also support church-state separation.

As the Center’s recent study noted, churches and (in some cases) other religious institutions in several Western European countries are funded through a mandatory tax on registered members. People can opt out of the tax by deregistering from their churches, but roughly seven-in-ten or more of respondents in the surveyed church-tax countries say they pay the tax.

Eight-in-ten adults in Denmark and three-in-four in Austria (76%), for example, say they pay the church tax – responses that indicate a willingness to make the payment, even though the actual shares of Danes and Austrians who pay church taxes may be lower. In both countries, more than half of respondents (76% in Denmark and 56% in Austria) also say religion should be kept separate from government policies.

Because Americans are accustomed to the principles governing the relationship between the state and religion contained in First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, they might find it strange that people in Europe could favor separation of church and state while simultaneously supporting a church tax. Yet it was efforts in the 19th century to separate church and state in Europe that helped give rise to the tax, which was introduced as an independent source of funding after many European governments scaled back their direct financial support of clergy.

This may help explain why people in countries with a church tax don’t differ much on this question from people in countries without such a tax. Indeed, comparable majorities in countries without a church tax also say that religion should be kept separate from government policies, including 72% in Belgium and 68% in both the Netherlands and France, according to a separate 2017 Pew Research Center report of 15 Western European countries.

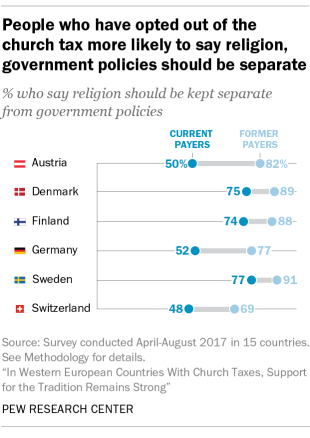

This doesn’t mean that the church tax makes no difference in how people view church-state relations. In fact, although majorities in all six church tax countries say they support the separation of church and state, this position is less popular among those who say they pay the church tax than among those who have opted out of it.

In Austria, for example, people who say they pay the church tax are substantially less likely to favor church-state separation than those who no longer pay the tax (50% vs. 82%). A similar pattern is seen in Germany (52% vs 77%).

In Austria, for example, people who say they pay the church tax are substantially less likely to favor church-state separation than those who no longer pay the tax (50% vs. 82%). A similar pattern is seen in Germany (52% vs 77%).

The difference in opinion between church-tax payers and those who have opted out may be fueling a wider debate in these countries about religious freedom and the role of churches in European societies today. In 2017, for example, the European Court of Human Rights ruled against five complainants in Germany who had argued that their obligation to pay the tax for their religiously affiliated spouse (as part of jointly filed tax returns) was a violation of their religious freedom.

Views on church-state relations vary in the three Western European countries that give taxpayers the voluntary option of making a donation to a religious organization: Italy, Portugal and Spain. In Italy and Portugal, support for church-state separation is on the lower end of the scale, at 55% and 56%, respectively. But in Spain, support for separation of church and state is quite high (75%).