Elections to the European Parliament haven’t always been the highest-profile of political contests – the twice-a-decade campaigns typically draw far fewer voters to the polls than corresponding national elections. But this week’s voting, scheduled for May 23-26 in the European Union’s 28 member countries, is being more closely scrutinized than usual. Right-wing populist parties are looking to dramatically increase their presence in the 751-seat assembly, the only directly elected piece of the EU’s complex constitutional machinery; one observer calls the vote “something of a referendum on the whole 60-year European Union experiment.”

One might expect that members of the European Parliament (or MEPs) would, by the nature of their office, generally support the goals, policies and institutions of the EU. But for as long as there’s been a directly elected Parliament there have been Euroskeptic members. (Nigel Farage, who was the prime mover behind Britain’s 2016 referendum on EU membership and now heads the Brexit Party, has been an elected MEP since 1999.)

While there are many strands of Euroskepticism throughout the EU, political observers and academic researchers often distinguish between “hard” and “soft” varieties. Hard Euroskepticism has been defined as “a principled opposition to the EU and European integration,” while soft Euroskepticism refers to opposition to specific EU policy areas or “a sense that ‘national interest’ is currently at odds with the EU’s trajectory.”

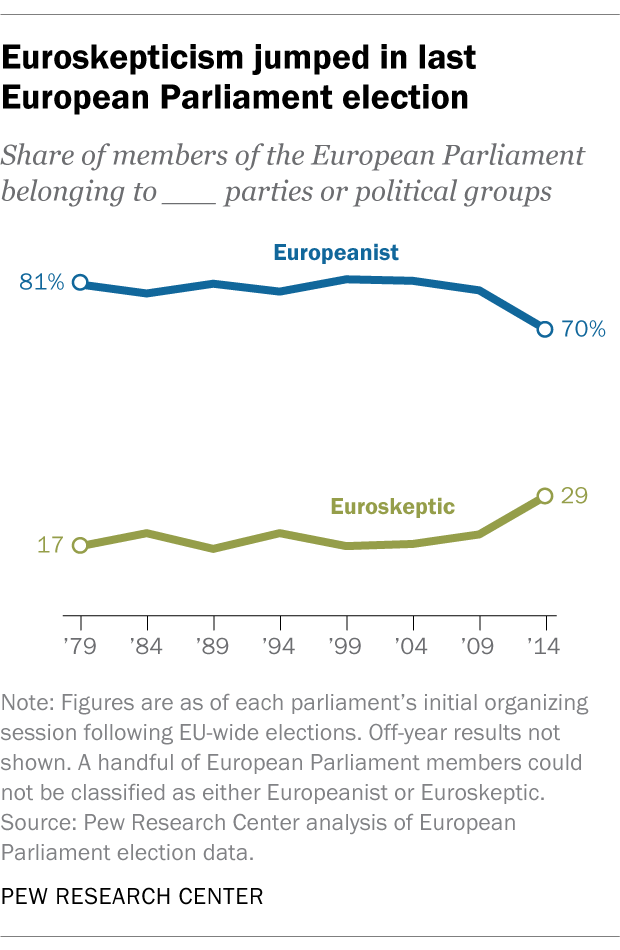

Roughly a fifth of MEPs were “hard” or “soft” Euroskeptics from 1979 to 2009, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of EU election results. In 2014, the Euroskeptic share jumped to 29%, or 221 MEPs; it’s now 30%, due to membership changes and shifts in political groupings. In the Greek and UK delegations, in fact, Euroskeptics outnumber pro-EU members.

Roughly a fifth of MEPs were “hard” or “soft” Euroskeptics from 1979 to 2009, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of EU election results. In 2014, the Euroskeptic share jumped to 29%, or 221 MEPs; it’s now 30%, due to membership changes and shifts in political groupings. In the Greek and UK delegations, in fact, Euroskeptics outnumber pro-EU members.

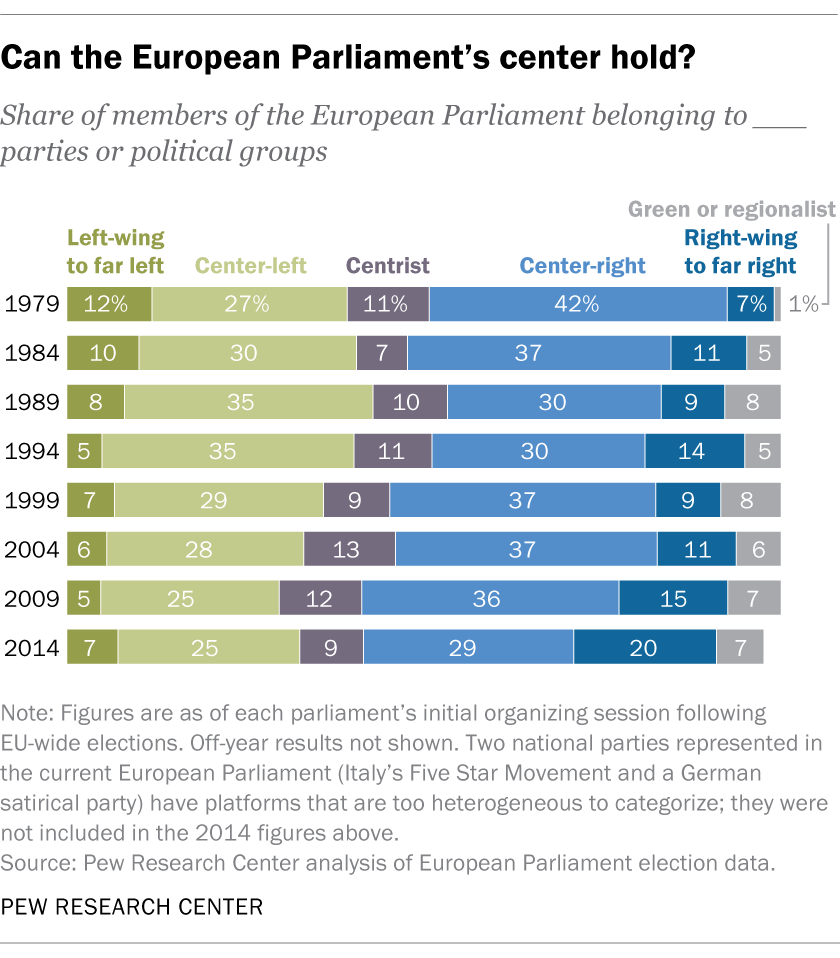

Concurrently, the center of political gravity in the European Parliament has shifted to the right. Historically, the three main groupings representing the center-left, center-right and centrist liberals held three-quarters or more of seats, but in the 2009 election their collective share slipped to 73%, and in 2014 it fell further to 64%. Parties classified as right-wing to far right now hold a fifth of European Parliament seats, more than double their share two decades ago. And after years of post-Cold War decline, parties categorized as left-wing to far left won 7% of seats in 2014, their biggest win in 15 years.

Concurrently, the center of political gravity in the European Parliament has shifted to the right. Historically, the three main groupings representing the center-left, center-right and centrist liberals held three-quarters or more of seats, but in the 2009 election their collective share slipped to 73%, and in 2014 it fell further to 64%. Parties classified as right-wing to far right now hold a fifth of European Parliament seats, more than double their share two decades ago. And after years of post-Cold War decline, parties categorized as left-wing to far left won 7% of seats in 2014, their biggest win in 15 years.

As the EU has expanded and ties between its member countries have deepened, the Parliament has evolved from mainly a “talking shop” to an institution with real power. Among its functions are the ability to amend and reject (though not propose) EU legislation, adopt the EU’s budget and oversee the European Commission, the EU’s executive body. (In 1999, in fact, it effectively forced the resignation of an entire Commission.)

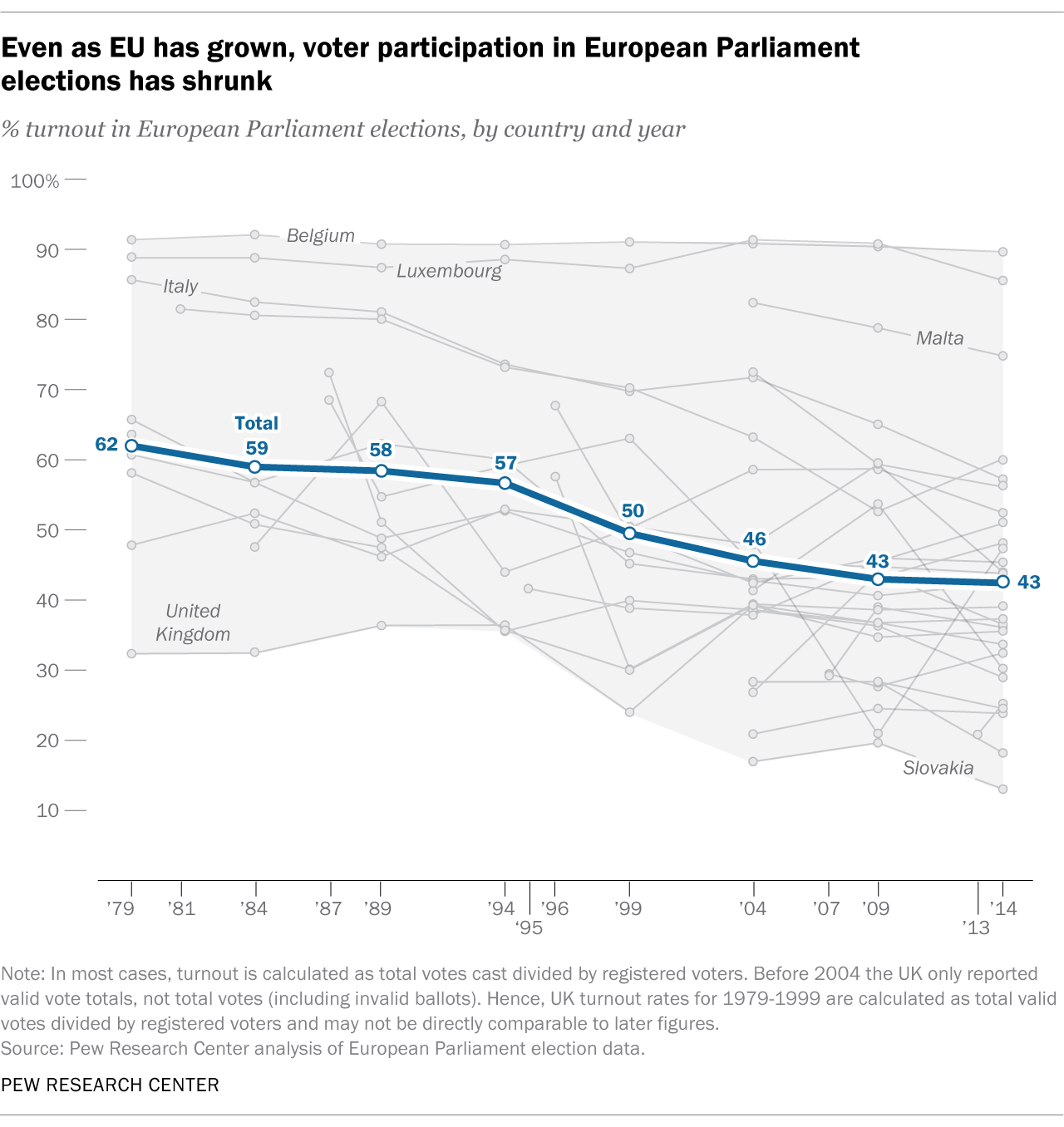

But even as MEPs have gained in power, EU citizens seem to have grown less interested in choosing them. In the first European Parliament elections in 1979, 62% of registered voters in the nine participating countries voted. Overall turnout has fallen in every election since: In 2014, just 43% of the 396.1 million registered voters cast ballots. In most EU countries, turnout in European Parliament elections typically lags well behind that in national elections.

See full European Parliament voter turnout data by country here (.xlsx).

While a few countries – notably Belgium and Luxembourg, both home to most of the EU’s central institutions – have had consistently high turnout rates in European Parliament elections, they’re very much the exceptions. In most EU countries, turnout either has dropped from initially high levels (in Germany, for example, turnout fell from 66% in 1979 to 48% in 2014) or started low and stayed there (such as in Slovakia, where turnout has never cracked 20% since the country joined the EU in 2004). Sweden is a notable exception: 51% voted in the 2014 European Parliament elections, up from 42% in 1995 when the country joined the bloc.

We obtained data on European Parliament membership and turnout from the Parliament’s website. For each Parliament, we focused on ideological divisions at the beginning of its five-year term; countries that joined the EU midway through a parliamentary term weren’t included until the next Parliament began.

Our analysis was primarily based on the European Parliament’s political groups, of which there are currently eight. Political groups are required to have a “coherent political complexion” and “common political affinity,” or they can be (and have been) disbanded. Accordingly, all members of a given group were assigned to the same position on the political spectrum and coded as “pro-EU” or “Euroskeptic” based on their group, unless there was a compelling reason not to. For example, Italy’s Five Star Movement belongs to the right-wing, Euroskeptic Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy group. While Five Star shares the Euroskepticism of the group’s other members, its heterogeneous political ideology sets it apart, and it was categorized as “other” politically.

MEPs who don’t belong to any political group (“non-inscrits”), as well as members of “mixed” groups that were allowed in previous years, were classified individually based on their national party membership and, in some cases, their public statements.