A federal judge in Texas made news in February when he ruled that the United States’ male-only draft is unconstitutional. Many Americans, though, might not be aware that the U.S. still has a draft.

It does, though mostly just on paper. For nearly four decades, the draft law’s only major requirement has been for men – but not women – to register with the Selective Service System within 30 days of their 18th birthday in case conscription is ever brought back.

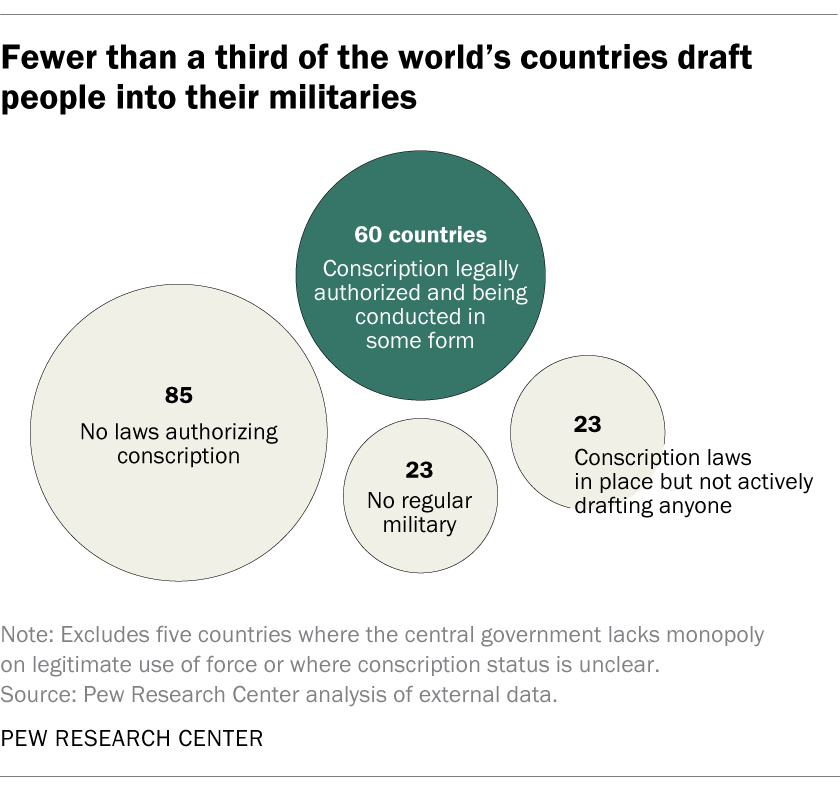

In fact, the U.S. is one of 23 countries where the military draft is authorized but not currently implemented. An additional 60 countries – fewer than a third of the 191 for which Pew Research Center found reliable information – have some form of an active conscription program. The other 108 countries we examined have no legal provision for compulsory military service; 23 of these don’t even have conventional armed forces.

In fact, the U.S. is one of 23 countries where the military draft is authorized but not currently implemented. An additional 60 countries – fewer than a third of the 191 for which Pew Research Center found reliable information – have some form of an active conscription program. The other 108 countries we examined have no legal provision for compulsory military service; 23 of these don’t even have conventional armed forces.

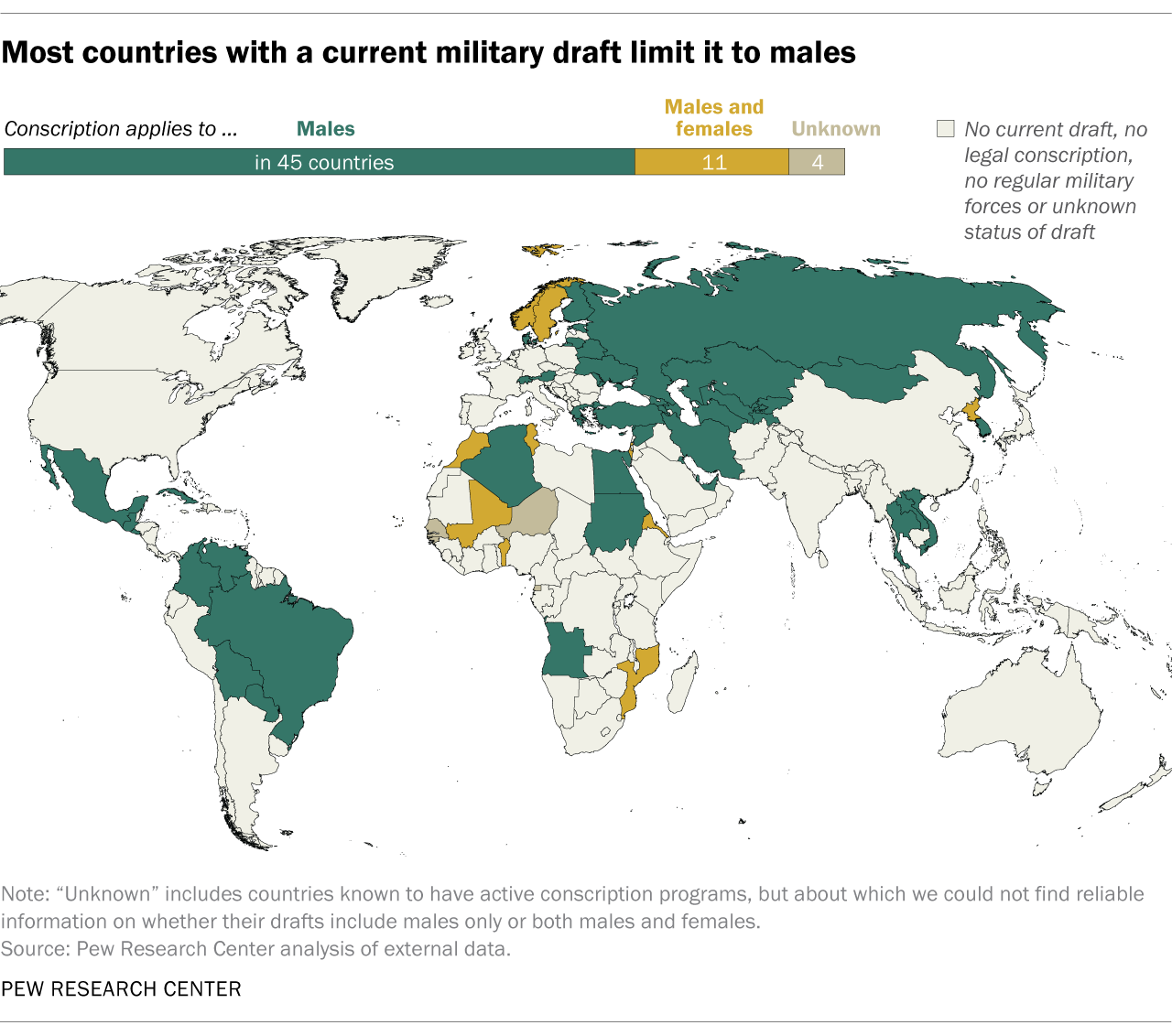

At least 11 of the 60 countries with active conscription programs draft both men and women. (For four countries with conscription – Equatorial Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Niger and Senegal – we couldn’t determine whether or not their draft systems include women.) In addition, some countries, such as Sudan and Vietnam, authorize conscription of women in law but draft only men in practice. And several other countries without active conscription programs – including Burma (Myanmar), Chad, Ivory Coast and Portugal – provide that if they ever do start drafting anyone, men and women would both be subject to call-up.

Conscription takes many forms around the world. The most common is a “universal service” requirement, in which all (or nearly all) of the target population is expected to serve a stint in the armed forces; the Israel Defense Forces, or Tzahal, are a well-known example. The required time ranges from a few months to several years, or even indefinitely.

Conscription takes many forms around the world. The most common is a “universal service” requirement, in which all (or nearly all) of the target population is expected to serve a stint in the armed forces; the Israel Defense Forces, or Tzahal, are a well-known example. The required time ranges from a few months to several years, or even indefinitely.

In “selective service” systems, the military chooses whom to draft from among all those registered based on its personnel needs; for everyone else, the registration itself fulfills their legal obligation.

Besides Israel, five other countries (Eritrea, Mali, Morocco, North Korea and Tunisia) conscript women as part of universal military service schemes; five (Benin, Cape Verde, Mozambique, Norway and Sweden) have selective service systems that encompass men and women.

However, the line between those broad categories can be quite fuzzy. Many countries that have universal service requirements on paper don’t actually induct all eligible people, for budgetary or policy reasons. In Norway, for example, the law requires all young people – including, since 2015, women – to serve for 12 months in the armed forces, followed by short “refresher” training periods (adding up to about seven additional months of service) till age 44. In practice, while all Norwegian citizens must register, no one is forced to serve against their will; in any given year, only about one-in-six registrants actually end up being conscripted.

On the other hand, some countries that ostensibly have no conscription have created such strong incentives to enlist that their systems resemble drafts. The Venezuelan Constitution, for example, forbids “forcible recruitment,” but also states that everyone has a duty to perform “such civilian or military service as may be necessary for the defense, preservation and development of the country.” All citizens, male and female, are required to register, and enlistees are guaranteed permanent access to certain government benefits, such as dental care and life insurance. Those who cannot prove they’ve served can’t attend university, get a driver’s license, work for the national or local governments or get state scholarship money.

Several nations have suspended or abolished conscription in recent years, including Albania, Ecuador, Jordan and Poland. Taiwan stopped drafting men last year, although conscription remains on the books and could be reinstated if there aren’t enough volunteers.

Other countries have gone in the opposite direction: Sweden reinstated compulsory military service in 2017, seven years after ending it. Morocco ended its draft in 2006 but reintroduced it in 2018. In both of those countries, women as well as men are now subject to being called up.

In 2013, a men’s rights group challenged the U.S.’s male-only registration requirement. After wending its way through the federal court system, the case reached a district court judge in Texas, who ruled that since qualified women can now serve in all military roles – including in combat – there’s no reason they should be exempt from having to register.

That decision may have surprised many Americans, especially those who came of age after active conscription ended in 1973. The National Commission on Military, National, and Public Service, a bipartisan panel created by Congress in 2016 to study the issue, recently called the current draft registration system “a mystery to most Americans,” adding that many “seem to be unaware of the purpose of the system and the process by which they register.” The commission also found that many Americans “are surprised that women are currently neither required nor permitted to register for selective service and question the rationale for excluding women from the obligation to defend the nation.” (Its final report and recommendations to Congress about how to increase participation in the military and other public service fields is due by March 2020.)

There is no single comprehensive, reliable, up-to-date source for information on countries’ conscription policies. This analysis relies on a wide variety of sources, including the CIA’s World Factbook, “The Military Balance” from the International Institute for Strategic Studies, the European Union Institute for Security Studies, and GlobalSecurity.org, an online provider of background information on the world’s militaries. We also consulted publications from individual countries’ governments, when available, and reports from various nonprofit organizations, think tanks and media outlets.