Under a peer-to-peer evaluation process established in the late 2000s, every member state in the United Nations faces a periodic review of its human rights record by countries on the UN Human Rights Council. But the issues raised in these reviews can vary substantially depending on which countries are doing the reviewing, according to a Pew Research Center analysis.

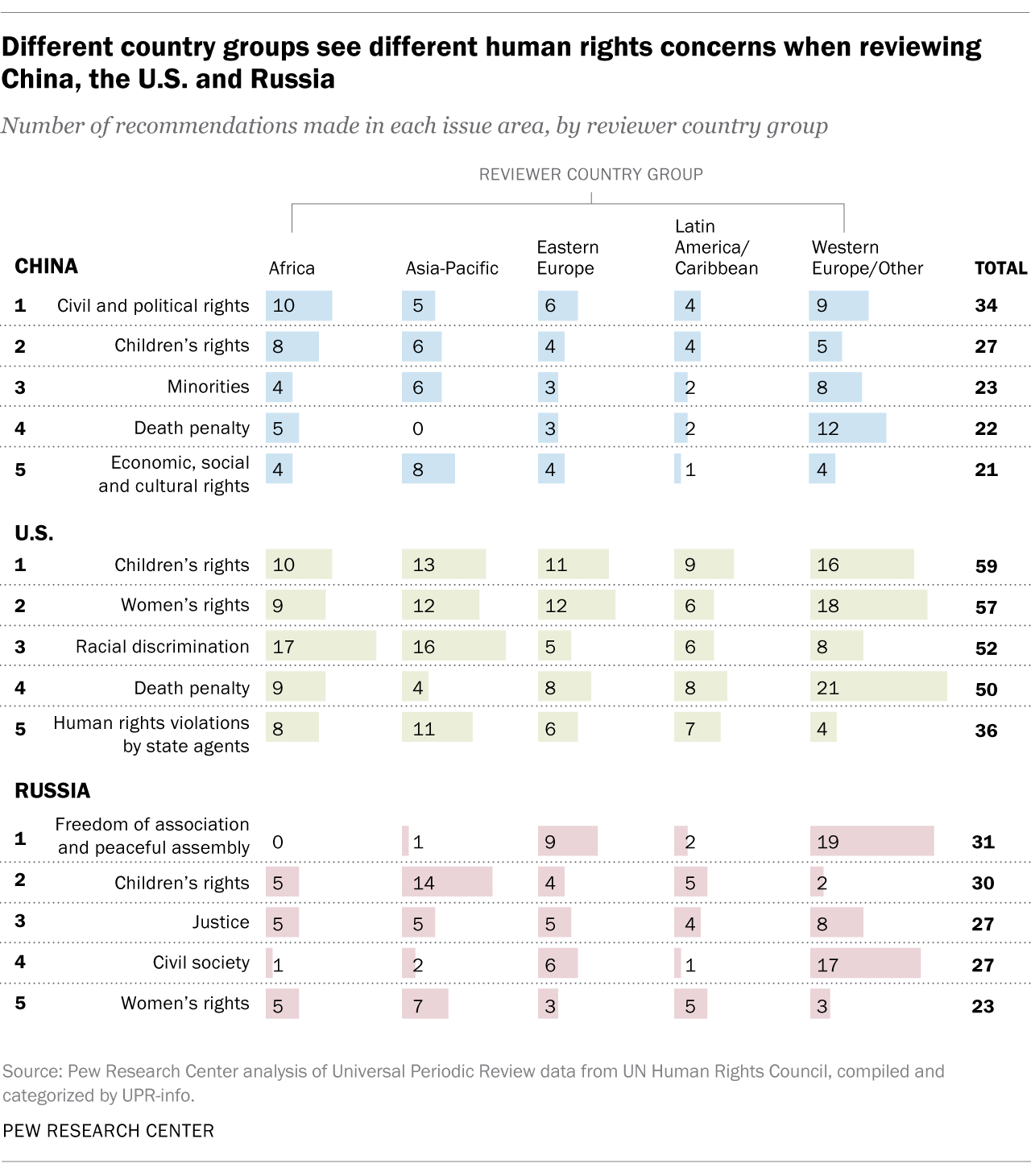

When the United States was last reviewed by its UN member peers, for example, countries in the Asian and African regional groups raised concerns about racial discrimination, while Latin American and Caribbean nations emphasized migrants’ rights. States in the Western European and Others Group (WEOG) often criticized the U.S. for its use of the death penalty.

Human-rights reviews of China and Russia also showed differences depending on the region of the reviewing nations. As they did with the U.S., WEOG countries criticized China over the death penalty, but Asian Group nations (including much of the Middle East) didn’t raise concerns about China’s use of capital punishment at all, focusing more often on economic rights and development.

These observations are drawn from the Center’s review of data from the Universal Periodic Review (UPR), a program from the UN Human Rights Council in which countries review each other’s human rights record and recommend improvements. The Center’s analysis relies on data compiled and categorized by UPR-Info, a nongovernmental organization that focuses on the UPR process.

The reviews are conducted by the UPR Working Group, which consists of representatives of the 47 Human Rights Council members. Working-group members serve three-year terms and represent different regional groups. All 193 UN member countries are reviewed over a staggered schedule, with each country reviewed every five years. After completing its review the working group issues recommendations for change, which the reviewed country can choose to either support (which is supposed to lead to an implementation plan) or merely note.

To get a sense of differing human rights priorities around the world, we examined how countries reviewed rights in three of the world’s major powers: the U.S., China and Russia. Since the reviews run in cycles, we looked at both the 2008-2011 and 2012-2016 periods, the latter being the most recent cycle for which data are available.

China, for instance, received very different advice from African countries than from Western European and Others Group nations. Between 2012 and 2016, development-related issues were among those most frequently commented on by countries in the African group, along with educational rights and general civil and political rights. For WEOG countries, by contrast, freedom of expression and religious freedom were among the most cited issues for China, trailing only the death penalty.

China, for instance, received very different advice from African countries than from Western European and Others Group nations. Between 2012 and 2016, development-related issues were among those most frequently commented on by countries in the African group, along with educational rights and general civil and political rights. For WEOG countries, by contrast, freedom of expression and religious freedom were among the most cited issues for China, trailing only the death penalty.

Issues in Russia related to sexual orientation and gender identity were cited much more frequently by countries in the WEOG in 2012-2016 than in the prior cycle. Those issues were the subject of 12 reviews, versus only one in the 2008-2011 period; no other regional group made sexual orientation/gender identity such a prominent part of their Russia reviews.

In both the 2008-2011 and 2012-2016 cycles, the death penalty was the top issue for WEOG countries in their reviews of both China and the United States. (These two nations are among the world’s top 10 countries for executions; Russia retains the death penalty in law but has a de facto moratorium on executions.) No other regional group cited death-penalty issues nearly as frequently in their reviews of China and the U.S.; the group of Asian countries, in fact, didn’t cite death-penalty concerns in China at all, in either time period.

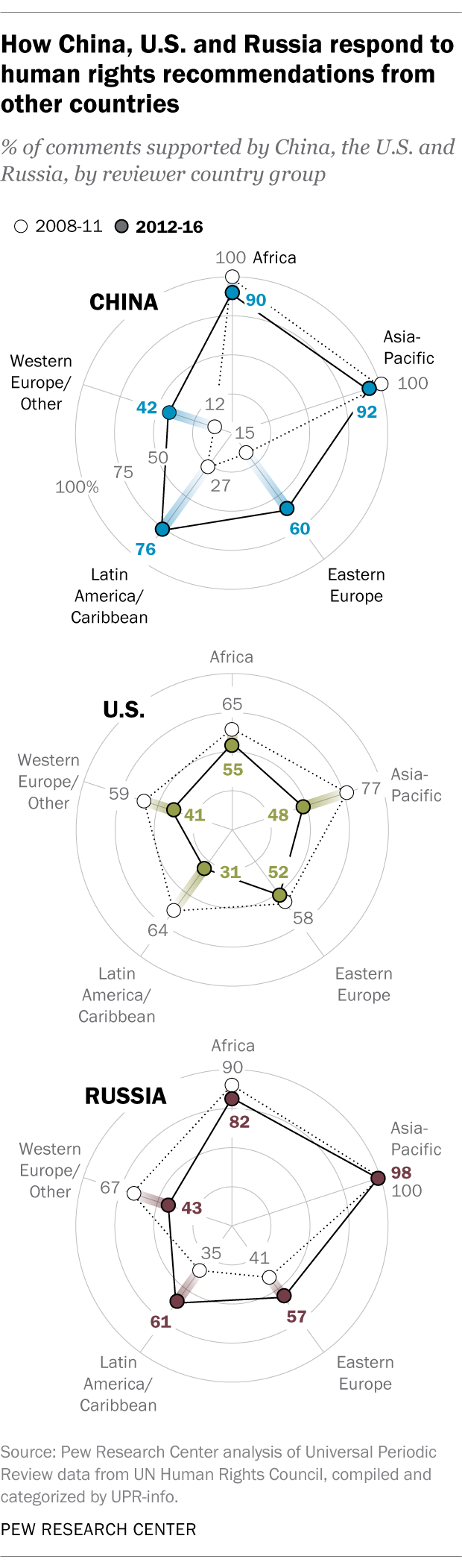

While people around the world generally have relatively negative views of whether China respects the personal freedoms of its people, China has become more willing to support other countries’ UPR recommendations over time. Between the two periods we studied, the percentage of recommendations China supported increased from 40% to 73%. Even among reviews from WEOG countries only (which tend to be the most critical), China’s rate of support increased from 12% to 42%.

While people around the world generally have relatively negative views of whether China respects the personal freedoms of its people, China has become more willing to support other countries’ UPR recommendations over time. Between the two periods we studied, the percentage of recommendations China supported increased from 40% to 73%. Even among reviews from WEOG countries only (which tend to be the most critical), China’s rate of support increased from 12% to 42%.

On the other hand, the U.S. has become less likely to support recommendations, with its overall support ratio declining from 65% to 45%. While the decline by the United States is apparent in recommendations from all country groups, the biggest drop comes regarding those submitted by countries in the Latin American and Caribbean Group: The U.S. supported 64% of recommendations from these nations in 2008-2011, but just 31% in 2012-2016.

Russia’s reactions to the UPR recommendations are mixed. Between the two periods studied, Russia became more likely to support recommendations from the Eastern European Group (41% to 57%) and the Latin American and Caribbean Group (35% to 61%). But the support ratio declined drastically for recommendations from the WEOG (67% in 2008-2011, 43% in 2012-2016).

About this analysis

The data used in this analysis are publicly available at UPR-Info, which categorizes the recommendations made by reviewing countries as part of the UN’s Universal Periodic Review process. UPR-Info groups recommendations made by reviewer countries into 56 issue categories. In this analysis, recommendations categorized as “international instruments” are excluded because they do not refer to substantive human rights issues. Also, recommendations made by reviewer countries can belong to multiple categories. For example, when South Africa reviewed China’s human rights record in the 2012-2016 cycle, it recommended steps that touched on both the “poverty” and “right to health” categories. In cases like these, both issues are counted.

The categorization of countries into regional groups follows that of the UN. The full names of the groups are: African Group, Asia-Pacific Group (which includes much of the Middle East), Eastern European Group, Latin American and Caribbean Group, and Western European and Others Group (which includes several non-European countries such as the U.S., Israel and Australia).