Germany is the birthplace of Martin Luther and the Protestant Reformation, but since the middle of the 20th century, the country has seen a dramatic shift away from Protestantism – one that has greatly outpaced a decline in the share of Germans who are Catholic.

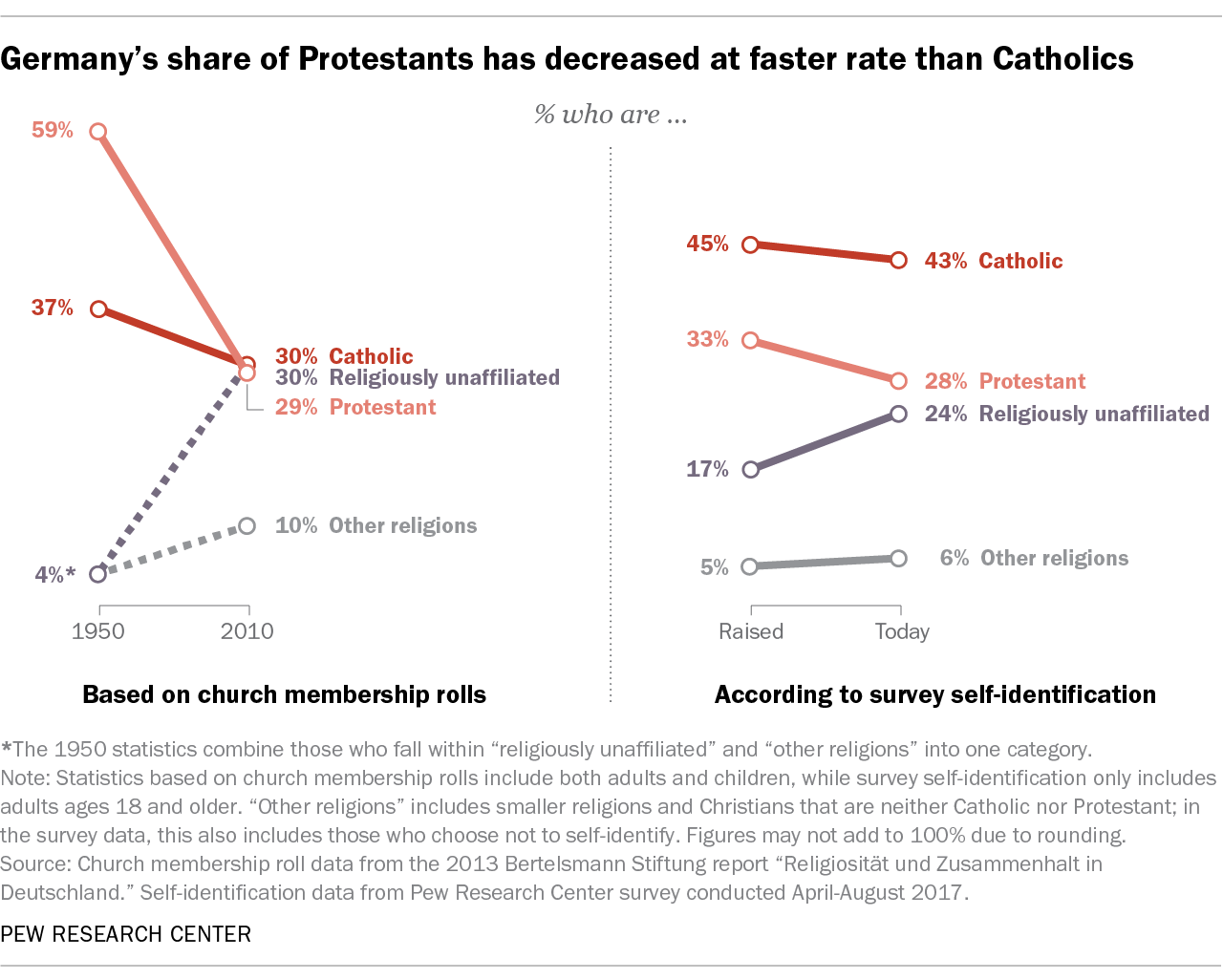

Protestants represented a majority (59%) of Germany’s population in 1950, with Catholics as a sizable minority (37%), according to research by Detlef Pollack and Olaf Müller, scholars of religion and sociology at the University of Münster in Germany. These shares are largely based on church membership rolls that include both children and adults. Over the next 60 years, the share of Protestants fell 30 percentage points, while the share of Catholics dropped 7 points. Each group now includes roughly three-in-ten Germans, based on 2010 membership data.

Declines in the shares of Protestants and Catholics have been accompanied by a rising share of the religiously unaffiliated, who accounted for 30% of Germans in 2010, up from fewer than 4% in 1950. And recent research indicates that the share of Muslims in Germany also has been growing in recent years, due in large part to immigration.

Declines in the shares of Protestants and Catholics have been accompanied by a rising share of the religiously unaffiliated, who accounted for 30% of Germans in 2010, up from fewer than 4% in 1950. And recent research indicates that the share of Muslims in Germany also has been growing in recent years, due in large part to immigration.

The nationwide decline in German Protestants also is apparent when looking separately at East and West Germany (which reunified in 1990), according to additional research by Pollack. The decline in East Germany, which was predominantly Protestant when the country was formed in 1949, is widely considered to be the result of persecution, repression and marginalization of religion during the roughly four decades of communist rule. (Today, eastern Germany is much more religiously unaffiliated than western Germany.)

In western Germany, several aspects of religious life have been cited as possible reasons for the steeper declines among Protestants. These include a strong Catholic identity forged from years of existence as a minority religion, and doctrinal differences over salvation that make formal church involvement more necessary for Catholics than for Protestants.

A recent Pew Research Center analysis also shows a drop in the share of Protestants in Germany. Among adults asked about their current religious denomination (which may be different from what is recorded in church membership rolls) and the denomination in which they were raised, there has been a decline in the share of Protestants (33% raised Protestant to 28% currently Protestant). The share of those who say they are Catholic has largely remained stable: 45% were raised Catholic and 43% currently identify as Catholic.

How German Protestants and Catholics compare

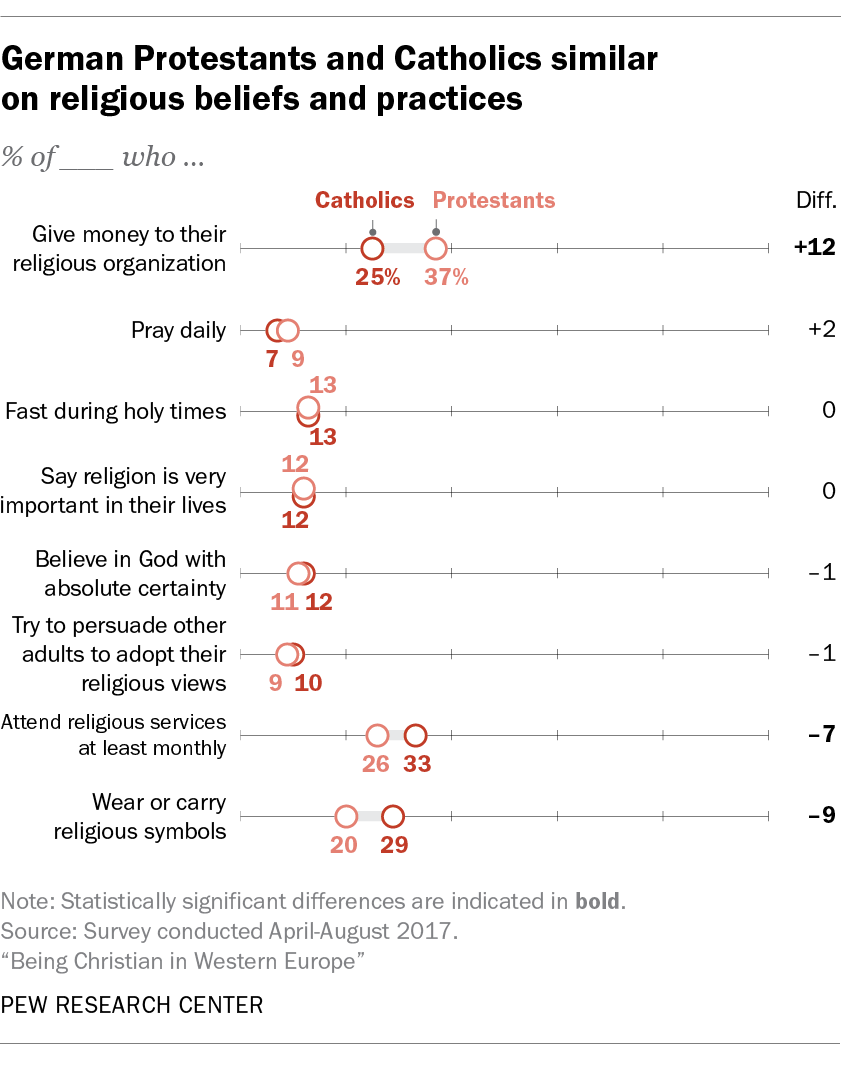

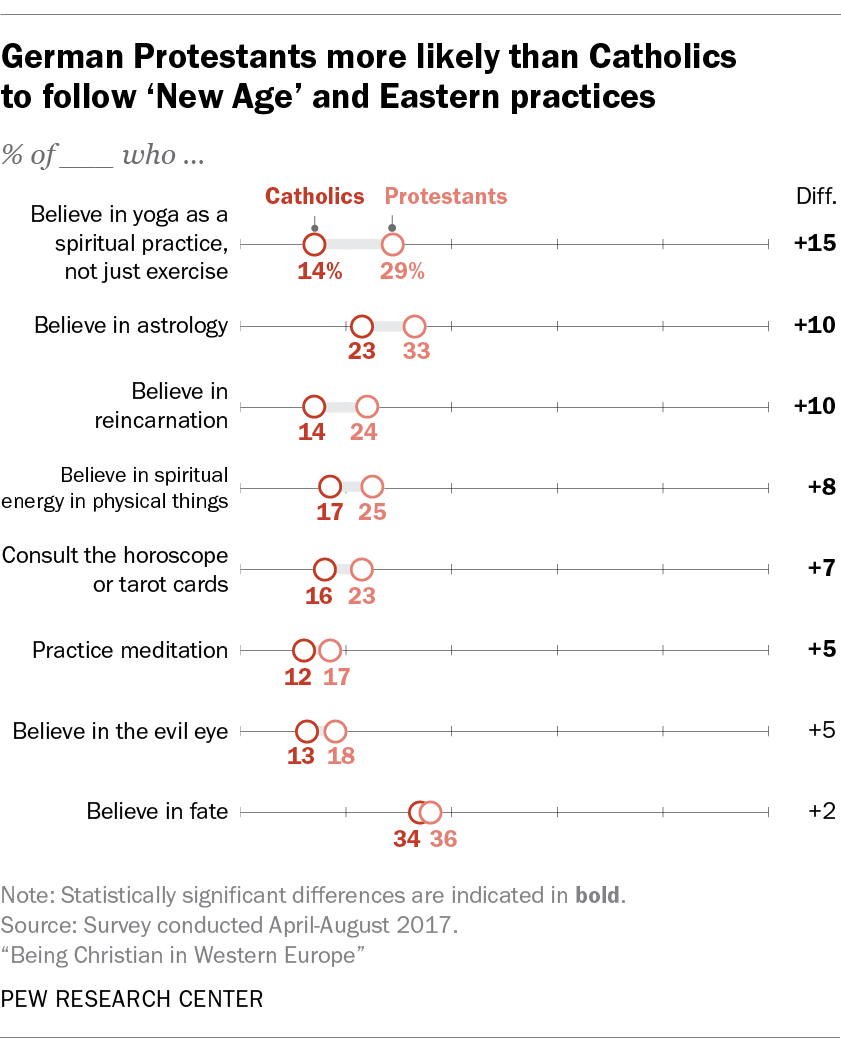

Protestants and Catholics in Germany follow traditional Christian religious beliefs and behaviors at roughly similar rates, according to Pew Research Center data. For example, similar shares in both groups say they pray daily and believe in God with absolute certainty. At the same time, German Protestants are more likely than their Catholic counterparts to follow Eastern or New Age spiritual practices and beliefs. A third of German Protestants, for instance, believe in astrology, while only 23% of Catholics do. And about one-quarter of Protestants consult the horoscope, tarot cards or fortune tellers (23%), compared with 16% of Catholics.

The recent Pew Research Center survey, which was conducted in 15 Western European countries, also examined attitudes on nationalism, immigration and religious minorities through the lens of religious affiliation and commitment. It found that, in general, Christians across Western Europe are more likely than the religiously unaffiliated to score higher on the Center’s 10-point Nationalist, anti-Immigrant and anti-religious Minority (NIM) scale. A higher score indicates higher levels of nationalism and negative sentiments toward immigrants and religious minorities. In Germany, for example, 29% of Christians score in the upper half of the scale, but only 18% of the religiously unaffiliated do.

Among German Christians, however, Catholics are more likely than Protestants to profess nationalistic attitudes and to express anti-immigrant and anti-religious minority attitudes. Moreover, Catholics who attend church services at least monthly are much more likely than Catholics who attend less frequently (and Protestants at either level of religious participation) to score in the upper half of the NIM scale. But it should be noted that Catholics and Protestants in Germany are concentrated in different parts of the country, which could also help shape attitudes on these topics.