There were nearly 467,000 apprehensions at the U.S.-Mexico border in 2018, the most for any calendar year since at least 2012, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of the most recent available data from U.S. Customs and Border Protection. The increase was driven in part by a dramatic spike in border apprehensions of family members at the end of last year.

Despite the increase, the number of border apprehensions in 2018 remained far below the levels throughout most of the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s, when around 1 million or more migrants were being apprehended each fiscal year.

The situation at the southwest border has become the focus of the now nearly month-long partial federal government shutdown. President Donald Trump and Democratic congressional leaders are at an impasse over Trump’s proposal for a wall at the border.

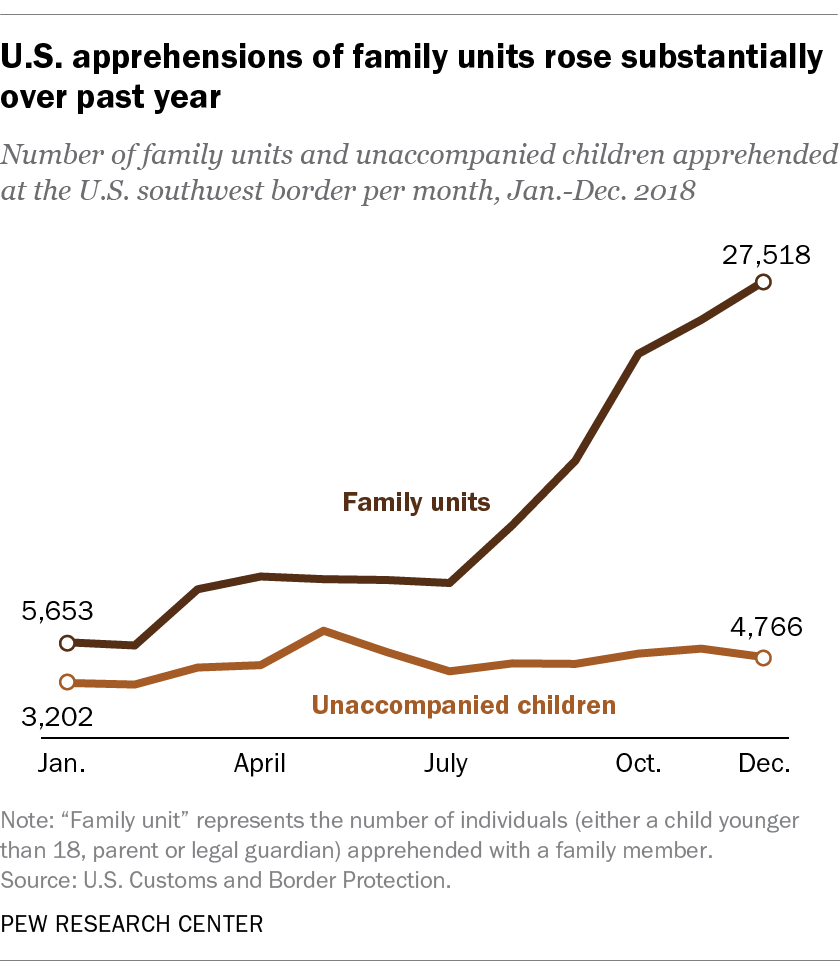

In the months leading up to the shutdown, there was a large increase in the number of people in family units apprehended at the border. Monthly family apprehensions subsequently hit new highs each month from September through December, according to data going back to 2012. There were nearly 17,000 family member apprehensions in September, more than 23,000 in October, about 25,000 in November and a record of more than 27,000 in December.

In the months leading up to the shutdown, there was a large increase in the number of people in family units apprehended at the border. Monthly family apprehensions subsequently hit new highs each month from September through December, according to data going back to 2012. There were nearly 17,000 family member apprehensions in September, more than 23,000 in October, about 25,000 in November and a record of more than 27,000 in December.

All told, roughly 163,000 family members were apprehended last year – more than three times as many as in 2017, and the highest number since at least 2012.

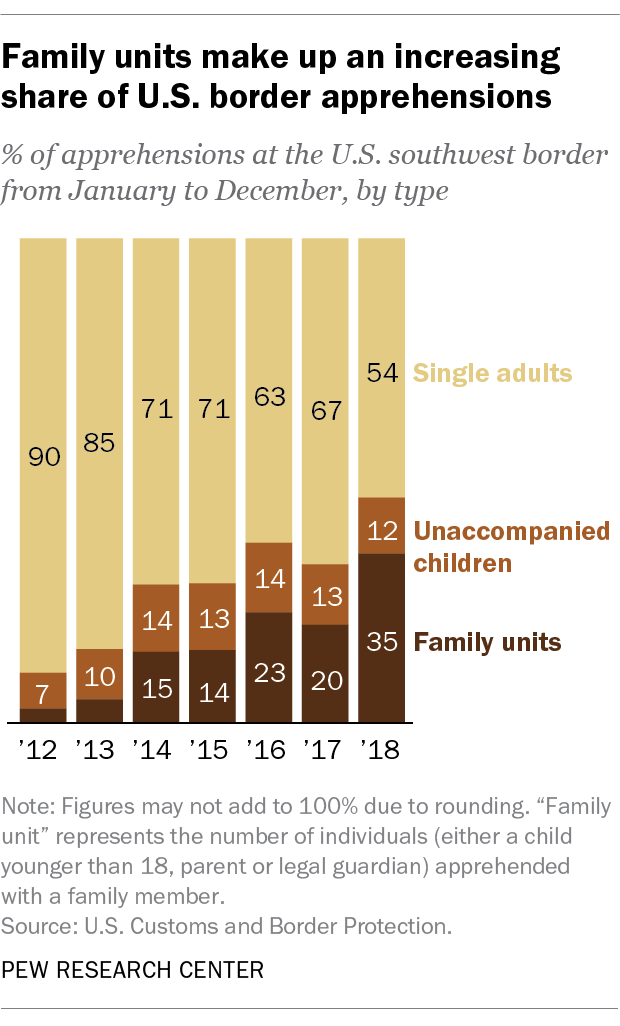

Family members accounted for about a third (35%) of all border apprehensions in 2018 – the highest share within the past seven years. The months leading up to the shutdown drove this increase: Family member apprehensions in December made up more than half (54%) of total southwest border apprehensions that month, the fourth consecutive high since September (40%).

Family members accounted for about a third (35%) of all border apprehensions in 2018 – the highest share within the past seven years. The months leading up to the shutdown drove this increase: Family member apprehensions in December made up more than half (54%) of total southwest border apprehensions that month, the fourth consecutive high since September (40%).

Border agents also apprehended nearly 54,000 unaccompanied children in 2018 – or 12% of the total – though this share was lower than in 2014 through 2016 (each 14%). (Unaccompanied child apprehensions do not include children who were apprehended as a family unit and later became unaccompanied as a result of prosecution initiatives.)

Besides unaccompanied children and family members, single adults continue to account for the largest share of border apprehensions: In 2018 there were nearly 250,000 single adult apprehensions, or 54% of the total. Still, the recent surge in family unit apprehensions is particularly notable because December 2018 marks the third time family member apprehensions exceeded single adult apprehensions, according to the Department of Homeland Security. The other two times were in October and November.

The apprehension of families and unaccompanied children received renewed attention following the Trump administration’s announcement of a “zero tolerance” policy in April last year. The policy led families to be separated at the border starting in May, though Trump ended the policy in an executive order in late June.

Family separations do still occur – such as when adult migrants traveling with children are apprehended at the border and deemed to be involved in criminal or gang activity – though more rarely than under the zero tolerance policy. From June 21 through November, 81 children were separated from 76 adult family members at the border, according to the Department of Homeland Security.

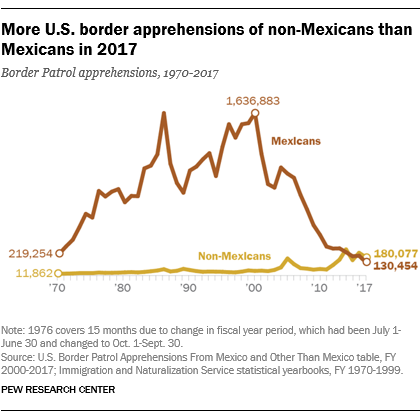

The vast majority of immigrant families and unaccompanied minors apprehended on the U.S.-Mexico border come from Mexico or the Northern Triangle region (El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras). (In December 2018, 95% of apprehended family members were from the Northern Triangle.) And in recent years, there have been more overall apprehensions of non-Mexicans than Mexicans at U.S. borders, reflecting a decline in the number of unauthorized Mexican immigrants coming to the U.S. over the past decade.

The vast majority of immigrant families and unaccompanied minors apprehended on the U.S.-Mexico border come from Mexico or the Northern Triangle region (El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras). (In December 2018, 95% of apprehended family members were from the Northern Triangle.) And in recent years, there have been more overall apprehensions of non-Mexicans than Mexicans at U.S. borders, reflecting a decline in the number of unauthorized Mexican immigrants coming to the U.S. over the past decade.

Many families are leaving countries with high levels of violent crime, a fact highlighted in 2017 by U.S. Vice President Mike Pence, who said “vicious gangs and vast criminal organizations” drive illegal immigration to the U.S. In 2016, El Salvador had the world’s highest murder rate (82.8 homicides per 10,000 people), followed by Honduras (at a rate of 56.5). Guatemala was 10th (at 27.3), according to data from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

Poverty represents another motivating force for migration from Central America. Northern Triangle nations are among the poorest in Latin America, and although some have seen a reduction of extreme poverty in recent years, high shares of people still live on less than $2 a day (the international poverty line is $1.90). Within Latin America and the Caribbean, Honduras has the second-highest share (16%) of people below the international poverty line, after Haiti (24%), according to the latest data from the World Bank. Guatemala is fourth-highest at 9%. In El Salvador, 2% of people live below $2 a day.

Given the level of poverty in the region, some migrants seek out economic opportunity in the U.S. in hopes of sending money back to their home countries. Most remittance dollars flowing to Latin America come from the U.S., and for Northern Triangle countries in particular, remittances make up a relatively large share of each country’s gross domestic product. In Honduras, for example, remittances were 19% of the nation’s GDP in 2017, according to data from the World Bank. In comparison, remittances were about 3% of Mexico’s GDP last year.

For unaccompanied children, family reunification could also be a strong driver. Among children from the Northern Triangle who were apprehended by the U.S. between January 2014 and April 2015, 60% were released to a parent already living in the U.S. Fewer than 10% were released to a non-family sponsor, such as a family friend or a person the family had no previous relationship with, according to an analysis by the U.S. Government Accountability Office.

Note: This is an update of a post originally published July 6, 2018.