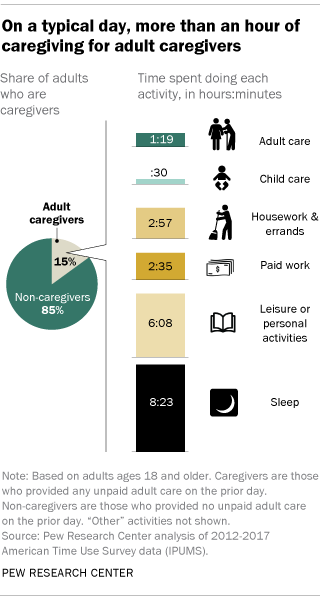

About one-in-seven U.S. adults (15%) provide unpaid care of some kind to another adult, according to a new Pew Research Center analysis of data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. And caregiving is often seen as a very meaningful activity for those providing care.

Adult caregivers are people who report providing any adult care on the prior day, as measured by the BLS’s American Time Use Survey, which tracks how Americans spend their time in a given day. Caregiving includes providing hands-on assistance with tasks such as dressing, eating and bathing, or even medical care, as well as providing transportation to appointments or helping to maintain the homes or finances of those who receive care. Caregiving can be provided to any adult who needs it – be it a relative, friend or neighbor – either due to age-related limitations or special cognitive or medical needs. (See additional tables for a detailed list of caregiving activities included in this analysis.)

Adult caregivers are people who report providing any adult care on the prior day, as measured by the BLS’s American Time Use Survey, which tracks how Americans spend their time in a given day. Caregiving includes providing hands-on assistance with tasks such as dressing, eating and bathing, or even medical care, as well as providing transportation to appointments or helping to maintain the homes or finances of those who receive care. Caregiving can be provided to any adult who needs it – be it a relative, friend or neighbor – either due to age-related limitations or special cognitive or medical needs. (See additional tables for a detailed list of caregiving activities included in this analysis.)

On average, adult caregivers in the United States spend almost an hour and 20 minutes a day providing unpaid assistance, but there is wide variation. About one-in-five caregivers (22%) spend less than 20 minutes a day on caregiving, while at the other end of the spectrum, 11% spend three hours or more a day providing care.

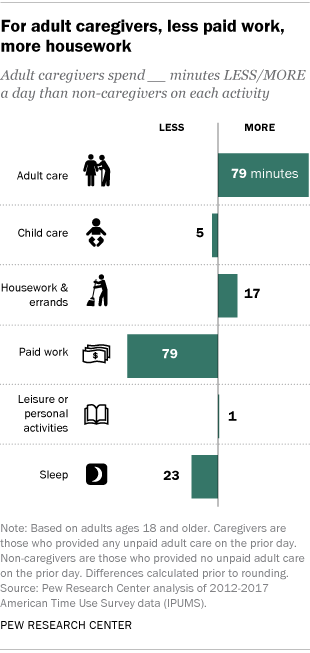

In addition to the time they spend on adult care, caregivers spend an average of 2 hours and 57 minutes a day doing housework and errands – 17 minutes more than non-caregivers spend on these activities each day. Non-caregivers, in turn, spend more time on paid work: almost four hours a day, compared with 2 hours and 35 minutes a day spent by those who provide unpaid adult care. (This difference remains even when looking only at those who are employed.) Adult caregivers also trail non-caregivers by 23 minutes in the amount of sleep they get daily.

In addition to the time they spend on adult care, caregivers spend an average of 2 hours and 57 minutes a day doing housework and errands – 17 minutes more than non-caregivers spend on these activities each day. Non-caregivers, in turn, spend more time on paid work: almost four hours a day, compared with 2 hours and 35 minutes a day spent by those who provide unpaid adult care. (This difference remains even when looking only at those who are employed.) Adult caregivers also trail non-caregivers by 23 minutes in the amount of sleep they get daily.

Women and men are about equally likely to be adult caregivers and provide similar amounts of daily care. There are also no notable differences by income, educational attainment or race and ethnicity in the share providing adult care. When it comes to the amount of time spent caring, however, caregivers with a high school diploma or less spend more time caring for adults than those with a bachelor’s degree or more (85 minutes vs. 72 minutes). Caregivers with family incomes of $30,000 or less also spend more time caring than their counterparts whose incomes are $75,000 or more (87 minutes vs. 73 minutes).

The analysis also finds that older adults, including those ages 75 and older, are about as likely as those in younger groups to provide unpaid care to another adult, and they spend at least as much time as younger caregivers doing so. Meanwhile, people who report that they themselves have a disability spend more time caring than those who do not have a disability – 95 minutes a day for disabled caregivers, compared with 78 minutes for other caregivers.

About half of caregiving experiences seen as very meaningful

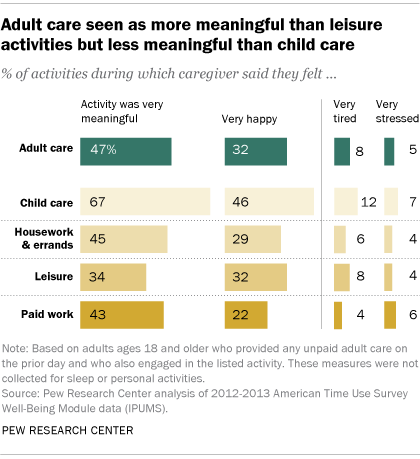

The act of caring for an adult is often a very meaningful one for those who do it. Caregivers rated about half (47%) of their caregiving experiences this way, according to the BLS data. Those who provided adult care said they were very happy during about a third (32%) of these activities as well. But they also reported being very tired during 8% of adult caregiving activities and very stressed during 5% of these activities.

The act of caring for an adult is often a very meaningful one for those who do it. Caregivers rated about half (47%) of their caregiving experiences this way, according to the BLS data. Those who provided adult care said they were very happy during about a third (32%) of these activities as well. But they also reported being very tired during 8% of adult caregiving activities and very stressed during 5% of these activities.

Paid work and housework were rated as very meaningful by caregivers about as often as adult care was. Caregivers rated a smaller share of their leisure activities (34%) as very meaningful, but among the 24% of adult caregivers who also provided child care, a far higher share (67%) saw those child care activities as very meaningful.

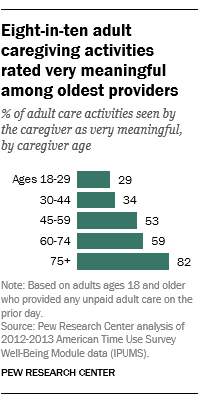

For the oldest caregivers, adult caregiving was particularly rewarding, but also more burdensome. Caregivers ages 75 and older said 82% of their adult caregiving activities were very meaningful. This figure fell to 59% among caregivers ages 60 to 74 and as low as 29% among those ages 18 to 29.

Caregivers ages 75 and older also said that they were very happy during about half (48%) of their adult caregiving activities, while these shares were far lower among younger respondents. At the same time, the oldest caregivers reported more tiredness related to adult caregiving than their youngest counterparts: Older caregivers said they felt very tired during 15% of their caregiving activities, while younger caregivers were tired during 8%.

Disabled caregivers also reported being tired during a larger share of caregiving activities than other caretakers (20% vs. 7%). But caregivers with disabilities rated themselves as very happy during a somewhat larger share of these activities (39% vs. 31%).

Note: Detailed tables of category classifications and demographic data can be found here (PDF).

This analysis is based primarily on time diary data from the American Time Use Survey (ATUS), which has been sponsored by the Bureau of Labor Statistics and annually conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau since 2003. The ATUS produces a nationally representative sample of respondents, drawn from the Current Population Survey. Most of the Pew Research Center analyses are based on respondents in the 2012-2017 ATUS samples. Multiple years of data were combined in order to produce large enough sample sizes to allow for subgroup analysis.

The diaries record each respondent’s primary daily activities (meaning, the main thing they were doing) sequentially for the prior day, including the start and end times for each activity. In some cases, secondary activities are collected in time diary data as well. For example, if a respondent was keeping an eye on their kids while their main activity was making dinner, child care could be considered their secondary activity.

In order to determine the prevalence of adult caregivers, any respondent who recorded any adult care as a primary activity on the prior day is counted as an adult caregiver; in addition, any respondent who reported that they provided any elder care on the prior day (which may have been as a primary activity, or a secondary activity) is also counted as an adult caregiver. For the analyses of daily time use and well-being, only those people who engaged in adult care as a primary activity are counted as caregivers.

The Well-Being Module of the ATUS was administered in 2010, 2012 and 2013 only. On it, ATUS respondents rated three randomly chosen activities from their time diaries (other than personal care and sleep, and any activities lasting fewer than five minutes, which were not eligible for rating) on several dimensions. These dimensions include the meaningfulness of the activity; how happy they were while doing the activity; how stressed they were; and how tired they were, using a scale from 0 to 6 (where 0 means they didn’t have the feeling at all, and 6 means they felt the feeling very much). The Pew Research Center analysis of the Well-Being Module is based on 2012 and 2013 data, so that the time period for the well-being analysis overlaps with the time period for the other analyses in the report. All data were accessed via the ATUS-X website made available through IPUMS.

See also: More than one-in-ten U.S. parents are also caring for an adult