Note: See this post for more recent charts on views of the U.S. and Trump.

America’s global image today is complicated. On balance, people around the world continue to give the United States favorable ratings and say it respects the individual liberties of its people. More countries also prefer the U.S. as the world’s leading power over China. At the same time, many express frustration about America’s role in the world and say they have little confidence in President Donald Trump to do the right thing in world affairs, according to a new Pew Research Center survey of 25 nations.

Here are nine charts that show how people in these countries see the U.S. and its president:

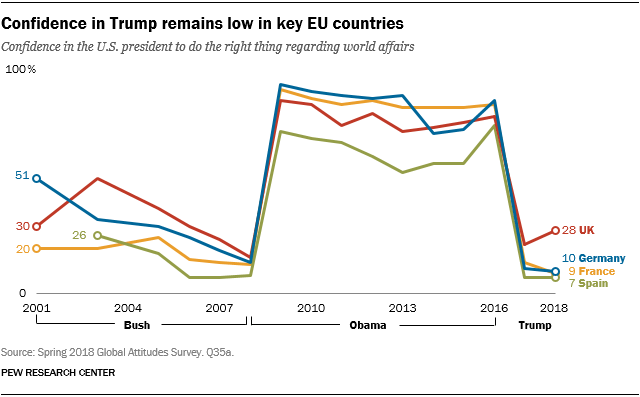

1Western Europeans have strikingly negative views of Trump. In the United Kingdom, Germany, France and Spain – four nations the Center has consistently surveyed over the past 15 years – there is a clear pattern in public perceptions of U.S. presidents. People in these countries generally had little confidence in President George W. Bush to do the right thing regarding world affairs. Their confidence was much higher in Bush’s successor, President Barack Obama, but it plunged following Trump’s election in 2016. This year, confidence in Trump remains low in Germany, France and Spain – but it is up slightly in the UK. Of the 25 countries surveyed, a median of 70% lack confidence in Trump to do the right thing regarding world affairs.

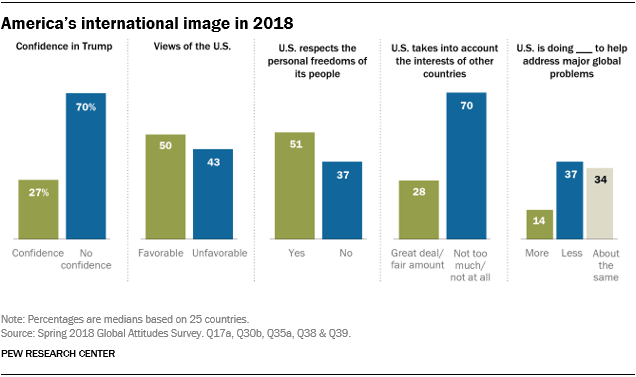

2Views of the U.S. are favorable on balance, but concerns are evident. Across the 25 countries surveyed, a median of 50% have a favorable opinion of the U.S., while 43% have an unfavorable view. Likewise, a median of 51% say the U.S. respects the personal freedoms of its people, compared with 37% who say it does not. However, there is international concern about America’s role in world affairs. Large majorities say the U.S. doesn’t take the interests of other countries into account when making foreign policy decisions. Also, a global median of 37% believe the U.S. is doing less to help address major global problems than it used to.

3 People in other nations have long said the U.S. does not take the interests of their country into account when making international policy decisions. There have been some shifts over time, however. In 2007, near the end of the George W. Bush years, a 71% median across 14 surveyed countries said the U.S. does not take other countries’ interests into account, while another 26% said it does. Attitudes shifted somewhat at the start of the Obama administration in 2009, when 36% said the U.S. considers other countries’ interests – including much larger increases in certain countries, such as Germany (+27 percentage points), France (+23), the UK (+19), South Korea (+19), Canada (+18) and Russia (+12). Today, public sentiment in these 14 countries resembles that of 2007, with a median of 72% saying the U.S. doesn’t consider other nations’ interests and 27% saying it does.

People in other nations have long said the U.S. does not take the interests of their country into account when making international policy decisions. There have been some shifts over time, however. In 2007, near the end of the George W. Bush years, a 71% median across 14 surveyed countries said the U.S. does not take other countries’ interests into account, while another 26% said it does. Attitudes shifted somewhat at the start of the Obama administration in 2009, when 36% said the U.S. considers other countries’ interests – including much larger increases in certain countries, such as Germany (+27 percentage points), France (+23), the UK (+19), South Korea (+19), Canada (+18) and Russia (+12). Today, public sentiment in these 14 countries resembles that of 2007, with a median of 72% saying the U.S. doesn’t consider other nations’ interests and 27% saying it does.

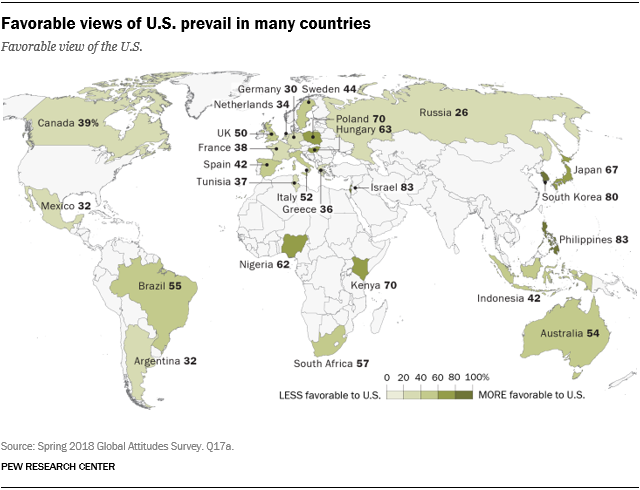

4The U.S. receives some of its highest favorability ratings in Asia. Meanwhile, half or more in four of the five Asia-Pacific nations polled view the U.S. favorably, including 83% in the Philippines and 80% in South Korea – both among the highest ratings in the study (along with 83% in Israel). America’s lowest rating came from Russia (26% favorable), which saw a 15-percentage-point decline in U.S. favorability over the past year – the largest drop among all surveyed countries. In America’s neighboring countries of Canada and Mexico, 39% and 32%, respectively, have a favorable view of the U.S.

5 Western Europeans now say the U.S. does not respect the individual liberties of its people – a reversal from just a few years ago. Views shifted most notably in France, Germany, Poland, Spain and the UK – five countries that have been surveyed since 2008. Among these countries, more now say the U.S. government does not respect the personal freedoms of its people (a median of 57%) than say it does (40%). As recently as 2013, a median of 76% across these nations said the U.S. does protect individual liberties, while a median of 18% said it does not. The decline began after the National Security Agency’s spying controversy during the Obama administration.

Western Europeans now say the U.S. does not respect the individual liberties of its people – a reversal from just a few years ago. Views shifted most notably in France, Germany, Poland, Spain and the UK – five countries that have been surveyed since 2008. Among these countries, more now say the U.S. government does not respect the personal freedoms of its people (a median of 57%) than say it does (40%). As recently as 2013, a median of 76% across these nations said the U.S. does protect individual liberties, while a median of 18% said it does not. The decline began after the National Security Agency’s spying controversy during the Obama administration.

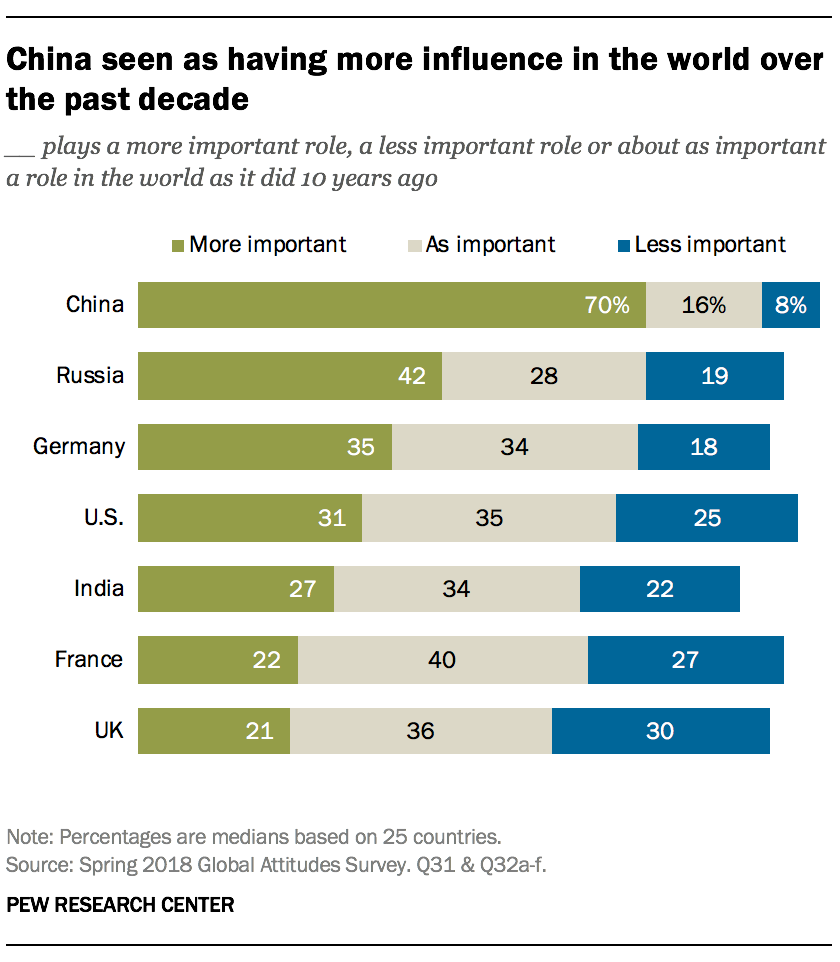

6 More say China is playing a larger role in the world compared with 10 years ago than say the same about the U.S. Respondents were read a list of seven major countries and were asked whether each is playing a more important, less important or as important role in the world compared with 10 years ago. Among the seven countries tested, China stands out: A median of 70% across 25 countries say it plays a more important global role than it did a decade ago, a significantly higher share than for the other six countries. The U.S. falls in the middle: Roughly similar medians say it is as important as 10 years ago as say its importance has grown.

More say China is playing a larger role in the world compared with 10 years ago than say the same about the U.S. Respondents were read a list of seven major countries and were asked whether each is playing a more important, less important or as important role in the world compared with 10 years ago. Among the seven countries tested, China stands out: A median of 70% across 25 countries say it plays a more important global role than it did a decade ago, a significantly higher share than for the other six countries. The U.S. falls in the middle: Roughly similar medians say it is as important as 10 years ago as say its importance has grown.

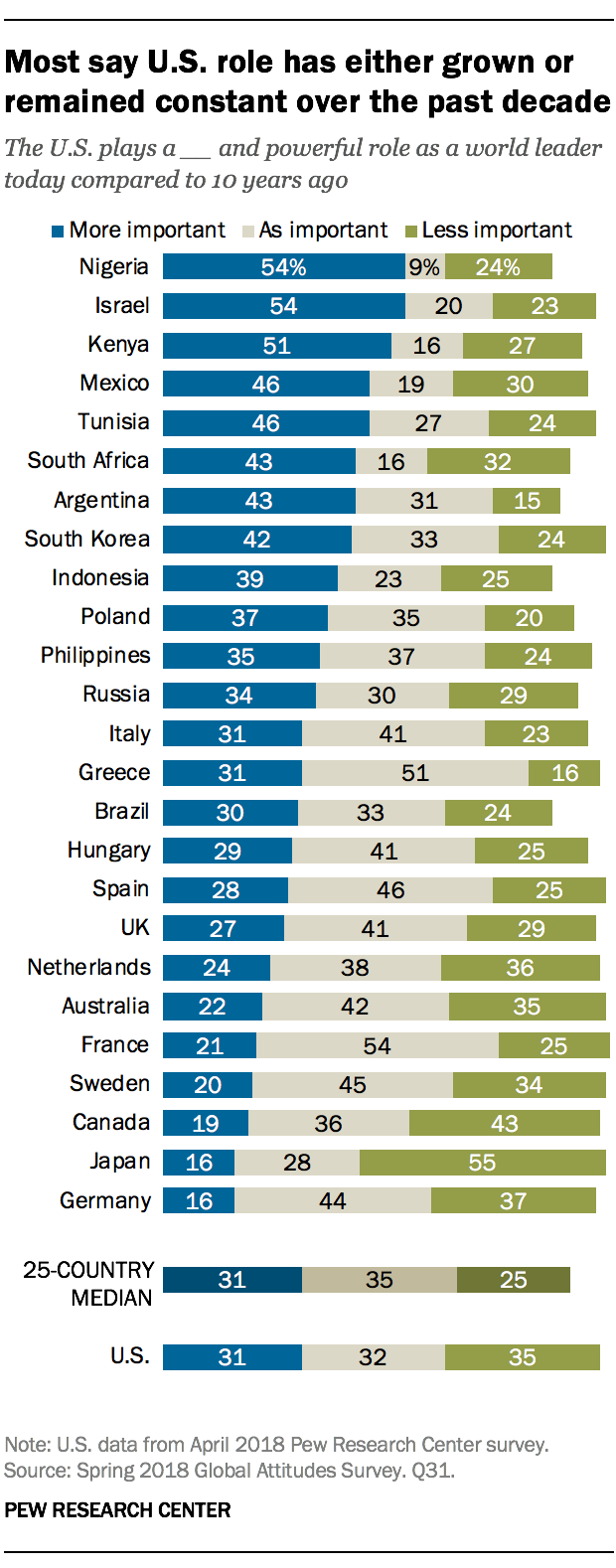

7 People are divided in their perceptions of how powerful a role the U.S. plays on the world stage compared with 10 years ago. A global median of 35% say the country is as important on the world stage as before, while 31% say it plays a more important role and 25% say it plays a less important role. Individually, most countries say the U.S. role has either grown or remains as important as before. Around half or more in Nigeria (54%), Israel (54%) and Kenya (51%) say the U.S. has grown in power and influence.

People are divided in their perceptions of how powerful a role the U.S. plays on the world stage compared with 10 years ago. A global median of 35% say the country is as important on the world stage as before, while 31% say it plays a more important role and 25% say it plays a less important role. Individually, most countries say the U.S. role has either grown or remains as important as before. Around half or more in Nigeria (54%), Israel (54%) and Kenya (51%) say the U.S. has grown in power and influence.

Japan stands out as the only country where a majority of people think the U.S. plays a less important role than it did 10 years ago. Only 16% of Japanese think the U.S. has grown in influence, equal to the share of Germans who say the same.

America’s neighboring countries offer different perceptions of America’s current role in the world: While 46% in Mexico say the U.S. plays a more important role today, only 19% of Canadians agree.

For their part, Americans themselves are divided on their own influence in the world, with nearly equal shares saying their country plays a more, equal or less important role than 10 years ago.

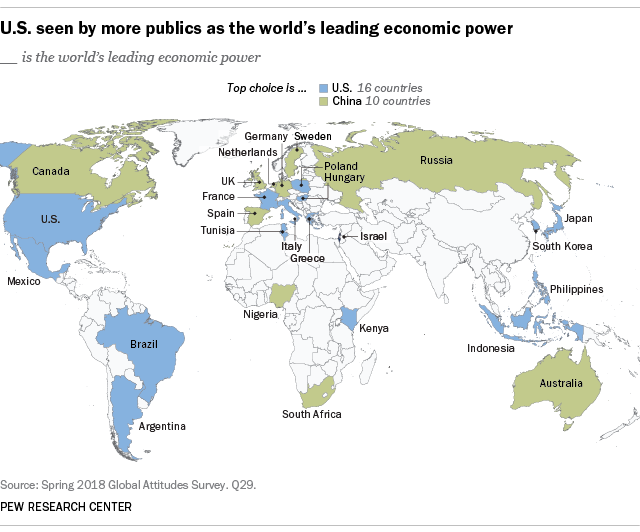

8America is seen as the world’s leading economic power. People in the surveyed countries tend to see the U.S. as the world’s leading economic power, though only by a slim margin over China (medians of 39% and 34%, respectively). Views vary somewhat by region. The U.S. is seen as the top economic power in all three Latin American countries – Brazil, Mexico and Argentina – and in nearly all Asia-Pacific countries surveyed. In sub-Saharan Africa, Kenyans name the U.S. as the world’s top economy, while Nigerians and South Africans name China (though margins are slim in these countries). Europeans are also divided: Those in several countries, including the Netherlands and Germany, choose China, while those in several others, including Hungary and Italy, choose the United States. Germany stands out for its large increase in the share who now name China as the globe’s dominant economy.

9 Most people prefer America over China as the world’s leading power. While many people believe China currently is the world’s top economic power, a median of 63% across the nations surveyed say having the U.S. as the world’s leading power would be better for the world. In contrast, just 19% say a world in which China was the leading power would be better.

Most people prefer America over China as the world’s leading power. While many people believe China currently is the world’s top economic power, a median of 63% across the nations surveyed say having the U.S. as the world’s leading power would be better for the world. In contrast, just 19% say a world in which China was the leading power would be better.

In the Asia-Pacific region, more prefer U.S. leadership over China. Preference for America is particularly high among China’s nearest neighbors: 81% of Japanese, 77% of Filipinos and 73% of South Koreans favor Washington’s leadership over that of Beijing.

Indonesia, Italy, Argentina, Russia and Tunisia are the only countries surveyed where about four-in-ten or fewer prefer U.S. leadership. Tunisia’s preference for China is particularly pronounced: It is the only country where a clear majority (64%) says having China as the world’s leading power would be better for the world.

In many countries, preference for U.S. leadership is linked to ideology, with those on the ideological right more likely than those on the left to prefer America as the world’s dominant power.

Correction (Jan. 4, 2019): Item No. 2 of this post and the graphics for items 6 and 7 have been corrected to reflect a revised weight for Australia in 2018. These changes do not materially change the analysis.