Nationalist populism has become a major force in European politics. But while such populism has long been thought to have its roots in economic anxiety, a new analysis of Pew Research Center survey data suggests there are additional factors at play.

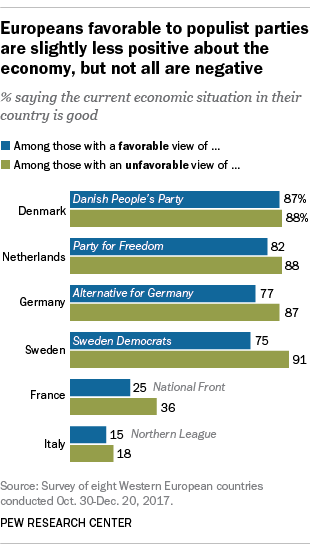

Those who have a favorable opinion of populist parties in Germany and Sweden, for example, are only slightly less likely than those with unfavorable views to be upbeat about the economy. Roughly three-quarters (77%) of those who have a favorable opinion of the populist Alternative for Germany party (AfD) say their country’s economic situation is good; that compares with 87% among other Germans. Similarly, three-quarters of those with a positive view of the populist Sweden Democrats party say their country’s economic situation is good, compared with 91% among other Swedes.

In other countries, populist party backers stand out less on the economy. In Italy, for instance, only 15% of the populist Northern League’s supporters give the Italian economy a thumbs-up, roughly on par with the 18% of others in the Italian public who also hold a downbeat view.

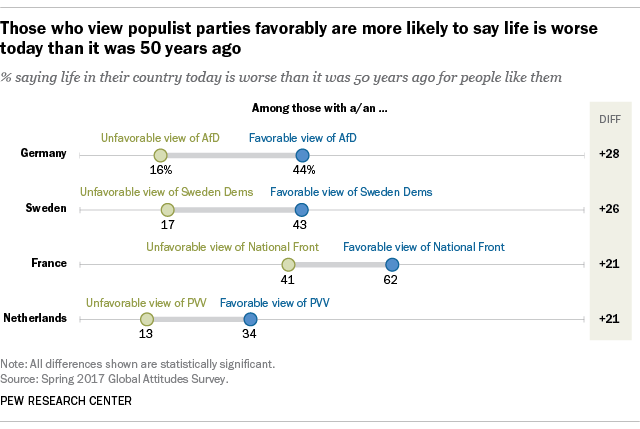

Nostalgia may be a better predictor of populist sentiments. Roughly six-in-ten French adults with a positive view of the populist National Front (62%) say life in France is worse today for people like them than it was 50 years ago. Only about four-in-ten (41%) of the rest of the French population share that perspective. In Germany, 44% of AfD supporters say life today is worse than 50 years ago; that compares with just 16% of other Germans. Those with populist sympathies in Sweden and the Netherlands similarly lament the passing of better times in the past.

(Related report: In Western Europe, Populist Parties Tap Anti-Establishment Frustration but Have Little Appeal Across Ideological Divide)

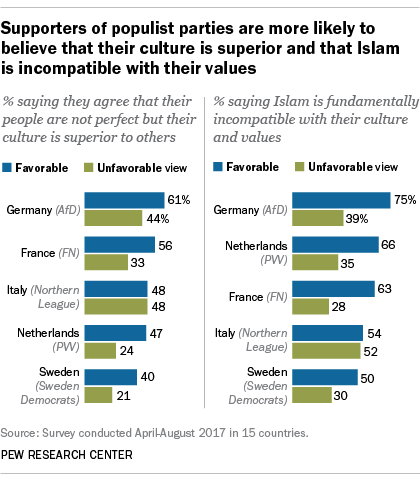

Ethnocentrism also plays a role in this wave of populist views. About six-in-ten (61%) AfD supporters in Germany, a majority (56%) of National Front backers in France and nearly half (47%) of Party for Freedom (PVV) adherents in the Netherlands say their people’s culture is “superior to others.” This sense of national cultural pre-eminence is far less prevalent among the rest of the publics in their countries.

Ethnocentrism also plays a role in this wave of populist views. About six-in-ten (61%) AfD supporters in Germany, a majority (56%) of National Front backers in France and nearly half (47%) of Party for Freedom (PVV) adherents in the Netherlands say their people’s culture is “superior to others.” This sense of national cultural pre-eminence is far less prevalent among the rest of the publics in their countries.

Another sentiment strongly expressed among those who support right-wing European populist parties is that Islam is fundamentally incompatible with their country’s culture and values: 75% of Germans with a positive view of AfD, 66% of Dutch PVV supporters and 63% of French National Front backers say Islam is “fundamentally incompatible with our culture and values.” About four-in-ten or fewer adults with unfavorable views of populist parties in these nations agree.

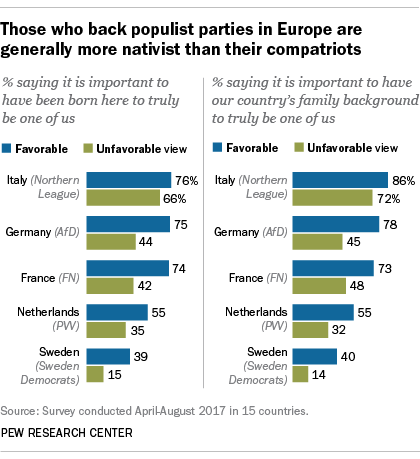

Old-fashioned nationalism is still evident in modern European right-wing populism, too.

Asked if it is important to have been born within France’s borders to be truly French, 74% of National Front adherents say yes, compared with 42% of the rest of French adults. A similar divide exists in Germany, where those who have a favorable view of AfD (75%) say one must be born in Germany to truly share the national identity, while only 44% of other Germans voice such opinions.

Asked if it is important to have been born within France’s borders to be truly French, 74% of National Front adherents say yes, compared with 42% of the rest of French adults. A similar divide exists in Germany, where those who have a favorable view of AfD (75%) say one must be born in Germany to truly share the national identity, while only 44% of other Germans voice such opinions.

Family ties to the homeland are also given primacy by those with favorable views of nationalist-populist parties. Roughly three-quarters of AfD backers (78%) and National Front supporters (73%), and more than half of PVV adherents (55%), believe it is important that people have family roots in their country to be truly German, French or Dutch. Roughly half or less of other French and Germans and only about a third of other Dutch adults agree.