U.S. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell’s recent decision to shorten the chamber’s August recess isn’t unprecedented. But in an election year – when a third of senators are on the campaign trail – it’s unusual, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of congressional session data going back to 1971, when the August recess was formally established.

The last time the Senate significantly abbreviated its August recess in an election year was 1994. That year, both the Senate and the House delayed the break as lawmakers worked primarily on health care and crime legislation. The Senate delayed its recess until Aug. 25; the House until Aug. 27.

This year, McConnell has said that senators will still be in recess for the first full week of August, but will return to Washington for the rest of the month. With the shortened break, senators will have more time to pass government spending bills and to approve presidential nominations, according to McConnell. Those nominees could include Brett Kavanaugh, President Donald Trump’s pick to fill retiring Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy’s seat. Last month, before Trump announced Kavanaugh’s nomination, McConnell said the Senate would vote on whomever Trump nominated before the November midterm elections.

House Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy said he has no plans for representatives to shorten their August recess, citing the House’s productivity.

The House did slightly shorten its August recess in 2010, which was also an election year. Then-Speaker Nancy Pelosi called representatives back to Washington about a week into their August break to vote on a $26 billion state aid bill. The interruption – which spanned just two days – riled lawmakers who were forced to cancel town halls and other campaign events ahead of the November midterms.

While both chambers have on occasion curtailed or interrupted the recess within the nearly 50 years we analyzed, they have never canceled it outright. In recent years, lawmakers have sometimes conducted “pro forma sessions,” a procedural tactic that allows Congress to technically remain in session even if most legislators are away. Pro forma sessions – which sometimes last less than a minute – can be used to prevent the president from making recess appointments.

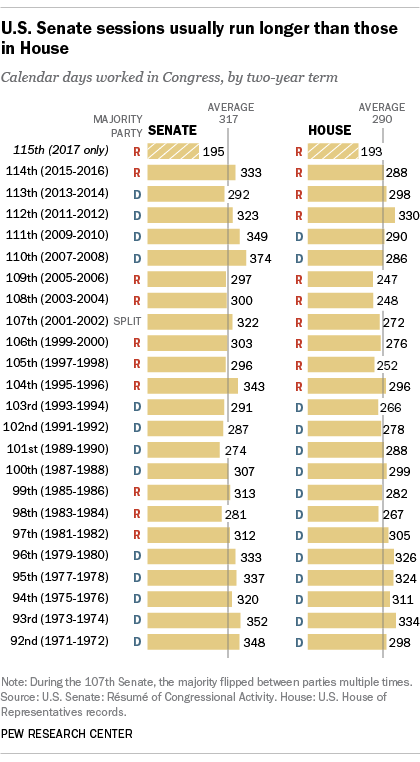

In both the current Senate and House, lawmakers are scheduled to be in session for more days than the average since 1971.

In the Senate, lawmakers spend an average 317 calendar days in session during a two-year congressional term, according to the Center’s analysis.

In the Senate, lawmakers spend an average 317 calendar days in session during a two-year congressional term, according to the Center’s analysis.

With McConnell’s announcement that this year’s August recess will be shortened, senators are on track to be in session for 385 days – far more days than average and the highest total of any Senate going back to 1971.

That current expected number counts the 195 days that the Senate was in session in 2017 and the 190 days that it has either already been in session or is scheduled to be in session this year. It also includes the additional three weeks – potentially 15 work days – that McConnell has added.

The longest Senate on record since 1971 took place during the 110th Congress (2007-08) and spanned 374 days. The shortest, during the 101st Congress (1989-1990), lasted just 274 days.

The House, meanwhile, typically convenes for fewer total days than the Senate during the course of a Congress. The House spends, on average, 290 days in session. The calendar the House has set for the term already has legislators working relatively more days – at 317 – than all but four previous Congresses since 1971.

The House spent the most days in session – 334 – during the 93rd Congress (1973-74). During the 109th Congress (2005-06) it was in session for the fewest, at just 247 days.

Our analysis looks at the number of calendar days spent in session for each two-year Congress using the Brookings Institution’s Vital Statistics on Congress database for the Senate and archival records for the House. We began our analysis with the 92nd Congress because it was the first to convene following the Legislative Reorganization Act of 1970, which mandates that both chambers recess in August. (The act grants each chamber’s leadership discretion to shorten its recess at any time.)

The recess was intended to give lawmakers scheduled time off from what had evolved into a grueling year-round legislative schedule. The recess also created an opportunity for legislators to spend time with constituents and their families away from the sweltering Washington heat.

Both the Senate and the House meet for two yearlong sessions – each beginning in January – and a long first session doesn’t always mean the second will be of similar length. Both chambers spend, on average, around a month less in Washington during the second session, which corresponds with an election year, than during the first. The House spends about 26 fewer days in session and the Senate about 22.

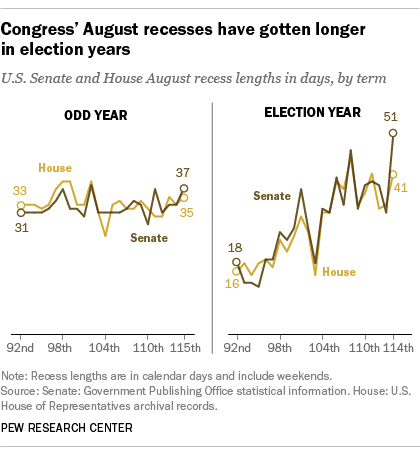

The average length for both chambers’ election year summer recess has roughly doubled since the 1970s and early ’80s. During election years between 1972 and 1982, the Senate spent an average of 16 days in August recess, and the House an average of 17 days. More recently, the Senate was in August recess for an average of 38 days in even years from 2006 to 2016, compared with an average of 36 days for the House.

The average length for both chambers’ election year summer recess has roughly doubled since the 1970s and early ’80s. During election years between 1972 and 1982, the Senate spent an average of 16 days in August recess, and the House an average of 17 days. More recently, the Senate was in August recess for an average of 38 days in even years from 2006 to 2016, compared with an average of 36 days for the House.

While this analysis focuses on historical highs, lows and averages, it’s important to note that congressional schedules can always change during the course of a session.