The religious landscape of Western Europe is changing. The Christian population is declining, while the share of religiously unaffiliated adults is increasing. The Muslim population is growing as a result of immigration and higher fertility rates. Meanwhile, the Jewish population appears to be on the decline due to emigration to Israel and other factors.

Against this backdrop, Pew Research Center asked people in 15 Western European countries a number of questions related to multiculturalism and pluralism, with a specific emphasis on their attitudes toward Muslims and Jews. These questions were part of a broader study on religion and identity in the region.

In this Q&A, Neha Sahgal, one of the lead authors of the study, discusses how the survey team constructed its questions and analyzed the results.

Is this survey intended to measure the extent of Islamophobia and anti-Semitism in Western Europe today?

The survey questions weren’t designed to measure anti-Semitism or Islamophobia in a comprehensive way, but rather to capture some expressed negative sentiment about these groups. We asked respondents about their willingness to accept Muslims and Jews as neighbors and relatives. We also asked questions about whether people think Islam is compatible with their country’s values and culture, and if they favor restrictions on Muslim women’s religious clothing. Another set of questions asked people if they agree or disagree with a number of strongly worded statements about Jews and Muslims.

When looking at the results, readers should keep a few things in mind. Survey respondents may harbor negative feelings toward Muslims and Jews, but not express them to an interviewer. Others may express negative feelings, but not have the opportunity or inclination to act in a hostile way toward Muslims and Jews living in their midst.

When looking at the results, readers should keep a few things in mind. Survey respondents may harbor negative feelings toward Muslims and Jews, but not express them to an interviewer. Others may express negative feelings, but not have the opportunity or inclination to act in a hostile way toward Muslims and Jews living in their midst.

Nonetheless, the survey provides not only cross-national results on these questions, but also some sense of the factors associated with these views.

What factors are correlated with negative sentiments toward religious and other minorities?

Perhaps not surprisingly, we found that Western Europeans who identify with the far-right side of the ideological spectrum in their country are more likely to express negative feelings about minorities and immigrants. Education is also a factor: People with less education are more likely to take negative positions toward Muslims, Jews and immigrants. And familiarity does not seem to breed contempt. On the contrary, Europeans who say they personally know a Muslim are less likely to express negative views of Muslims.

But there’s another interesting finding that jumps out of the data across the region. Self-described Christians in Western Europe are more likely than religiously unaffiliated adults to hold negative views toward immigrants and religious minorities. They’re also more inclined to express nationalist attitudes. This is true even when we use statistical techniques to control for factors including age, education, gender, political ideology and personal economic satisfaction. And it’s true both for highly observant Christians and for those who seldom go to church. In Finland, for example, 67% of Christians who attend church on at least a monthly basis, as well as 63% of those who attend less often, say “Islam is fundamentally incompatible with Finnish values and culture.” That compares with 54% of religiously unaffiliated Finnish adults.

Why this is the case is beyond the scope of our study, but we’re aware that there are some commentators in Europe who have suggested that Christian identity has become a kind of cultural marker for some Europeans – a way of differentiating themselves from newcomers and minorities – even if they are not particularly religious.

You mentioned some of the strongly worded statements about Jews and Muslims that you included in your survey. Why did you ask the questions in the way you did?

The survey asked respondents whether they agreed or disagreed with the following statements: “Jews always overstate how much they have suffered,” and, “In their hearts, Muslims want to impose their religious law on everyone else in our country.” We deliberately worded these statements very strongly so that if respondents say they agree with them, they are unambiguously registering an unfavorable sentiment toward the group.

Many of the interfaith leaders and scholars we consulted as we developed our questionnaire suggested that contemporary anti-Jewish tropes may include things like “overstating historical events” or “being unpatriotic.” And the idea that Muslims secretly want to impose religious law on everyone else is the subject of public discussion from time to time. Previous surveys by the Anti-Defamation League and others have tested some of these negative stereotypes and found substantial numbers of people who agree with them in many countries around the world.

Overall, we asked 22 questions related to the themes of nationalism, immigration and religious minorities. We combined the responses to all these questions to create a scale that provides an overall sense for attitudes on nationalism, immigration and religious minorities.

Why are unfavorable views about Muslims and Jews included in the same scale?

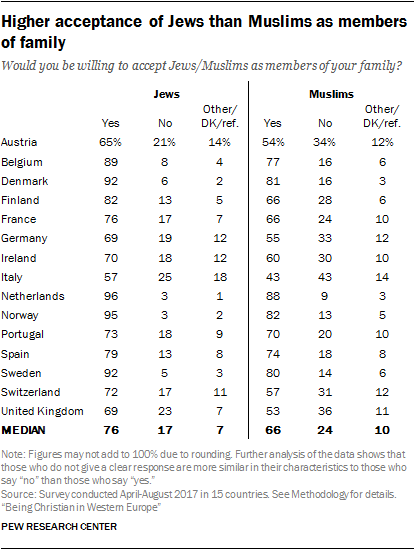

The survey results indicate that attitudes toward Jews and Muslims are highly correlated with each other. People who express negative opinions about Muslims are more likely than others to also express negative views of Jews. People who say they are unwilling to accept Muslims as members of their family are also more likely than others to say they are unwilling to accept Jews in their family.

The questions about Jews and Muslims also correlated well with many others we asked about nationalism, immigration and religious minorities, which is why we were able to group them all together into the scale.

Why doesn’t the report offer the opinions of Muslim and Jewish respondents?

In all of the countries we surveyed, Muslims make up less than 10% of the population, and Jews an even smaller sliver. These small population sizes are one reason it’s methodologically and logistically challenging to design a multi-country survey that allows us to adequately represent the opinions of these groups. Another challenge is that minority populations are often distributed differently throughout a particular country than the general population is. They may be mostly concentrated in urban areas, or in some countries, there may be a high concentration of Muslims or Jews in particular towns. Muslim populations in Europe also include many recent immigrants, many of whom may not speak the national language well enough to take a survey. For these and other logistical reasons, we were unable to adequately represent the views of Europe’s minority communities in this particular survey.