President Donald Trump has appointed 29 judges to the federal bench since his inauguration, including 14 appeals court judges and a Supreme Court justice, Neil Gorsuch. While Trump has moved quickly to put his stamp on the federal judiciary, his judges have also faced a record amount of opposition, at least based on the average number of Senate votes cast against them.

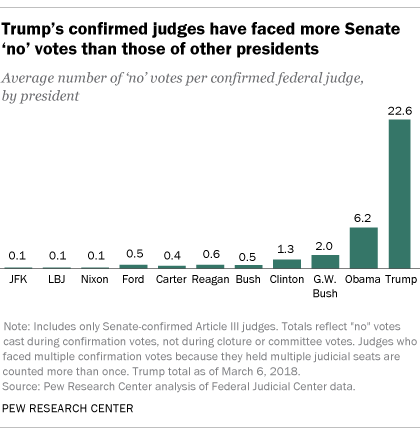

The 23 men and six women Trump has successfully appointed so far have faced a total of 654 “no” votes on the floor of the Senate, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of data from the Federal Judicial Center and the U.S. Senate. That works out to an average of nearly 23 votes against each confirmed judge – by far the highest average for any president’s judges since the Senate expanded to its current 100 members in 1959.

The 23 men and six women Trump has successfully appointed so far have faced a total of 654 “no” votes on the floor of the Senate, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of data from the Federal Judicial Center and the U.S. Senate. That works out to an average of nearly 23 votes against each confirmed judge – by far the highest average for any president’s judges since the Senate expanded to its current 100 members in 1959.

The 330 judges Barack Obama appointed during his eight years in office faced an average of six votes against them. George W. Bush’s 328 confirmed judges faced an average of two, and Bill Clinton’s 382 judges faced an average of just over one. (This analysis counts judges for each Senate confirmation vote they faced. Some judges held multiple judicial positions and are counted more than once. Clarence Thomas, for instance, is counted twice under George H.W. Bush’s total because Thomas was confirmed to two separate positions that each required a confirmation vote: first to a seat on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit in 1990, then to the Supreme Court in 1991.)

All but one of the votes against Trump’s nominees have come from Senate Democrats or from independents who caucus with Democrats. The lone Republican to vote against one of Trump’s judicial nominees on the Senate floor was Sen. John Kennedy of Louisiana, who opposed the nomination of Gregory Katsas to the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit.

It’s still early in Trump’s tenure and the pattern of opposition to his judicial picks could change. But in general, presidential appointments to the federal judiciary have become much more contentious in recent decades.

Just one of President John F. Kennedy’s 134 confirmed judges drew any “no” votes in the Senate. That was Thurgood Marshall, whom the Senate confirmed to the Court of Appeals for the 2nd Circuit on a 54-16 vote in 1962. (Four senators voted “present” on Marshall’s nomination; 26 others didn’t vote at all.) All of Kennedy’s other confirmed judges were approved on a voice vote – that is, without any recorded opposition.

Kennedy’s successor, Lyndon B. Johnson, also faced little Senate opposition to his judicial choices: All but two of his 186 confirmed judges were approved on a voice vote. (Marshall was again an exception: Eleven senators voted against him when Johnson nominated him as the Supreme Court’s first African American justice in 1967; 20 senators didn’t cast a vote.)

It wasn’t until the Clinton and George W. Bush presidencies that the Senate began regularly deciding on a president’s judicial nominees through roll call votes, rather than voice votes, a shift accompanied by an uptick in recorded opposition.

Of course, counting the average number of Senate floor votes against nominees who are ultimately confirmed doesn’t address those who are not confirmed. The Senate can register its opposition to nominees in other ways, such as by not voting on a nominee at all. That’s what happened in 2016, when the Republican majority blocked Obama’s Supreme Court nomination of Merrick Garland by declining to take action on it.

A different way of looking at the growing contentiousness of judicial appointments is by looking at the “success rate” of judicial nominations: that is, the share of each president’s nominees who end up being confirmed to the bench. While 99% of Kennedy’s court picks were confirmed, the rate was substantially lower for many subsequent presidents, including 78% for George H.W. Bush, 85% for Clinton, 86% for George W. Bush and 83% for Obama.

A different way of looking at the growing contentiousness of judicial appointments is by looking at the “success rate” of judicial nominations: that is, the share of each president’s nominees who end up being confirmed to the bench. While 99% of Kennedy’s court picks were confirmed, the rate was substantially lower for many subsequent presidents, including 78% for George H.W. Bush, 85% for Clinton, 86% for George W. Bush and 83% for Obama.

It’s too early to measure Trump’s success rate in any meaningful way. But at least three of Trump’s judicial nominees have withdrawn from consideration after running into early signs of opposition. Dozens of others are awaiting votes in the Senate. (It’s worth noting, however, that Trump has structural advantages that other presidents did not have. In addition to having a Senate controlled by his own party, his court nominees need only a simple majority – rather than 60 votes – to advance to the floor, following rules changes in 2013 and 2017.)

The rising discord in the federal judicial nominations process has been catalogued in other ways. For example, the amount of time that judicial nominees have waited for a confirmation vote in the Senate has grown significantly. A 2012 Congressional Research Service study found that the average and median wait times for “uncontroversial” judicial nominees – defined as those who faced little or no recorded opposition in the Senate – “increased steadily with each presidency, from Ronald Reagan’s to Barack Obama’s.” The increase affected district and appellate court nominees.

This analysis counts only Senate-confirmed, Article III judges who are included in the Federal Judicial Center’s biographical database. While our tally of the average number of Senate “no” votes counts judges for each federal judicial position held, our tally of the success rate for each president counts each nominee only once, regardless of how many times he or she may have been nominated or confirmed. That’s to allow for a more consistent comparison of success rates across administrations.