The U.S. has admitted more than 70,000 Iraqi and Afghan citizens over the past decade through special immigrant visa programs available to those who worked for the U.S. government during conflicts in their home countries, and Afghans account for a big majority of them, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of U.S. Department of State data.

Recipients of these special visas served as interpreters or translators or performed other key jobs in Afghanistan or Iraq for the U.S. government and in doing so put themselves and their families in danger.

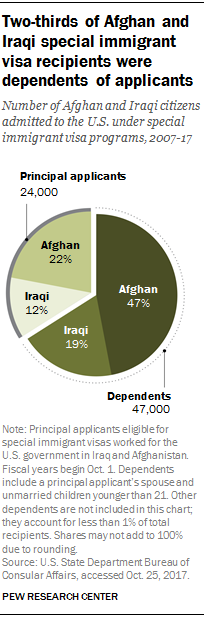

More than two-thirds of special immigrant visas have gone to Afghans (48,601) since fiscal 2007 – the first year visas were awarded under the programs – while Iraqis have received 21,961 such visas. Totals include visas issued to the principal applicants who worked for the U.S. government, as well as their spouses and unmarried children younger than 21. (These special visas make up a small slice – about 1% – of the overall number of U.S. immigrant visas awarded from fiscal years 2007 to 2017.)

More than two-thirds of special immigrant visas have gone to Afghans (48,601) since fiscal 2007 – the first year visas were awarded under the programs – while Iraqis have received 21,961 such visas. Totals include visas issued to the principal applicants who worked for the U.S. government, as well as their spouses and unmarried children younger than 21. (These special visas make up a small slice – about 1% – of the overall number of U.S. immigrant visas awarded from fiscal years 2007 to 2017.)

The majority of Iraqis (68%) issued special immigrant visas entered the U.S. prior to fiscal 2014. For Afghans, the opposite is true: Nearly all (92%) received special visas starting in fiscal 2014. Changes in visa allowances set by Congress are a key reason for the shifting balance of Iraqi and Afghan special visa recipients.

The application process can cost thousands of dollars and typically takes about one to three years to complete. More than 9,000 principal applicants from Afghanistan and almost 100 from Iraq had applications pending as of June 30, 2017, according to a government report.

A primary benefit of the programs is lawful permanent residence, which allows a person to live and work in the U.S. and offers a path to citizenship. To start the application process, applicants must submit several documents to the U.S. Embassy in their home country: proof of U.S. government employment, evidence of imminent threats due to their work and a letter of recommendation from a supervisor, as well as birth certificates and other documents for themselves and family members. Applicants and their family members must then complete an in-person interview, plus medical and security screenings. If denied, applicants may appeal decisions.

Iraqi and Afghan citizens may enter the U.S. on three separate special immigrant visa programs: a program exclusively for Afghans, another that is only for Iraqis, and a third for either Iraqis or Afghans employed by the U.S. as translators or interpreters. Eligibility and application deadlines vary by program.

In 2009, Congress authorized special immigrant visas for Afghan citizens under what today is the largest of the three programs. Since fiscal 2016, 7,000 visas have been made available, reflecting the continued U.S. military presence in Afghanistan. Under current rules, those eligible to apply must have worked on behalf of the U.S. government for at least two years in Afghanistan at some point since Oct. 7, 2001. Applications must be filed before December 2020, and the program will end when all allocated visas are taken.

The U.S. government rejected about 2,700 applications filed by Afghan citizens during the first nine months of fiscal 2017. (Approval rates are not available because decisions are not always made in the same year that an application is filed.)

In 2008, Congress created a program exclusively for Iraqi citizens. The program has been mostly phased out, as today the U.S. military has a smaller presence in Iraq than Afghanistan. The program’s size peaked in fiscal 2013 when Congress allocated 7,000 visas to be used by Dec. 31, 2013. In fiscal 2014, another 2,500 visas were allocated with no expiration date, though no new applications are being accepted.

The third program is for both Iraqi and Afghan citizens who have worked directly for the U.S. military as translators or interpreters for at least a year. Created by Congress in 2006, today this program has the lowest number of visas allocated – 50 principal applicants per year (though the annual cap was temporarily increased to 500 visas per year in fiscal 2007 and 2008). The number of visas awarded under this program peaked in fiscal 2008, when the U.S. admitted 1,116 translators or interpreters and their family members. (Some translators and interpreters may also qualify for special visas under the other two programs.)

The third program is for both Iraqi and Afghan citizens who have worked directly for the U.S. military as translators or interpreters for at least a year. Created by Congress in 2006, today this program has the lowest number of visas allocated – 50 principal applicants per year (though the annual cap was temporarily increased to 500 visas per year in fiscal 2007 and 2008). The number of visas awarded under this program peaked in fiscal 2008, when the U.S. admitted 1,116 translators or interpreters and their family members. (Some translators and interpreters may also qualify for special visas under the other two programs.)

Recipients of these special immigrant visas can receive refugee resettlement benefits from the U.S. government, which include 30 to 120 days of financial assistance. About 85% of those who have entered the U.S. under the special immigrant visa programs (from Oct. 1, 2007, to Sept 30, 2017) have received refugee assistance and resettled in states across the country. Top resettlement states during this time include California (17,416), Texas (10,598), and Virginia (7,249).