Americans have mixed feelings about using gene editing techniques to reduce babies’ lifetime risk of contracting serious diseases, with parents of children younger than 18 especially wary of the practice, according to a 2016 Pew Research Center survey.

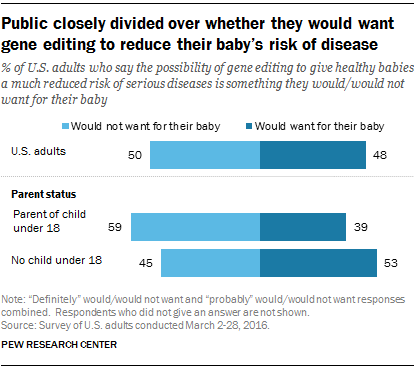

When asked to consider the idea of using gene editing to lessen healthy babies’ risk of disease, many more Americans said they were very or somewhat worried about the idea (68%) than were at least somewhat enthusiastic about it (49%). And the public was closely divided over whether they would or would not want gene editing for their baby (48% versus 50%). Parents of minor children were less inclined to want gene editing for their child by a margin of 39% to 59%.

When asked to consider the idea of using gene editing to lessen healthy babies’ risk of disease, many more Americans said they were very or somewhat worried about the idea (68%) than were at least somewhat enthusiastic about it (49%). And the public was closely divided over whether they would or would not want gene editing for their baby (48% versus 50%). Parents of minor children were less inclined to want gene editing for their child by a margin of 39% to 59%.

The survey underscores how the details of gene editing play an important role in public opinion. It was conducted before a recent breakthrough in gene editing that has raised the potential of significantly reducing the lifetime risk of diseases in healthy babies.

Another Pew Research Center survey conducted in 2014 had similarly found Americans closely divided over whether changing genetic characteristics to reduce a baby’s risk of serious diseases would be appropriate (46%) or taking advances too far (50%).

And while most in the 2016 survey said they expected the prospect of gene editing to usher in a “great deal” (46%) or “some” (35%) change for society, the public is also divided over the likely impact of this change. Slightly more Americans expected the benefits for society to outnumber the downsides of gene editing than vice versa (36% to 28%), while a third (33%) said the downsides and benefits would even out.

One particular concern about gene editing among scientists and bioethicists stems from the potential long-term implications of a type of gene editing – known as germline editing – that could change the human gene pool in the future. (Gene editing done only in somatic cells, by contrast, would not be passed on to future offspring.)

Asked specifically about this possibility, Americans are more reluctant to embrace gene editing when it could affect future generations. Roughly half of adults (49%) said gene editing would be less acceptable to them if the effects “changed the genetic makeup of the whole population,” versus just 17% who said it would be more acceptable. When asked about an alternate scenario in which the effects of gene editing are limited to a single person, more Americans said it would be more acceptable than less acceptable (34% to 23%).

Asked specifically about this possibility, Americans are more reluctant to embrace gene editing when it could affect future generations. Roughly half of adults (49%) said gene editing would be less acceptable to them if the effects “changed the genetic makeup of the whole population,” versus just 17% who said it would be more acceptable. When asked about an alternate scenario in which the effects of gene editing are limited to a single person, more Americans said it would be more acceptable than less acceptable (34% to 23%).

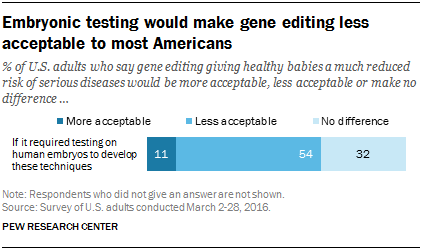

And queried on the possibility of using human embryos in the development of gene-editing techniques, a majority of adults (54%) – including two-thirds of those with high religious commitment – said this would make gene editing less acceptable to them, compared with just 11% who said it would make it more acceptable.

And queried on the possibility of using human embryos in the development of gene-editing techniques, a majority of adults (54%) – including two-thirds of those with high religious commitment – said this would make gene editing less acceptable to them, compared with just 11% who said it would make it more acceptable.

Some argue that public resistance to gene editing is a function of its novelty, and that as these techniques become more commonplace, public concerns will dissipate. Indeed, survey respondents who had heard at least a little about gene editing were more inclined to want gene modifications to reduce their child’s risk of serious diseases. But whether that pattern foretells the future is harder to say.

New biomedical developments have sometimes been met with initial resistance that fades away over time – one classic example is in vitro fertilization – but others, such as the idea of human cloning for non-therapeutic purposes, have been met with steady and overwhelming public resistance.