Roughly a quarter century after the collapse of the Soviet Union, religion has reasserted itself as an important part of individual and national identity in many places where communist regimes once repressed religious worship and promoted atheism, according to a major new Pew Research Center survey of 18 countries in Central and Eastern Europe. In addition to religious identity, beliefs and practices, and national identity, the survey explores respondents’ views on social issues, democracy, the economy, religious and ethnic pluralism, and more.

Here are nine key findings from the report:

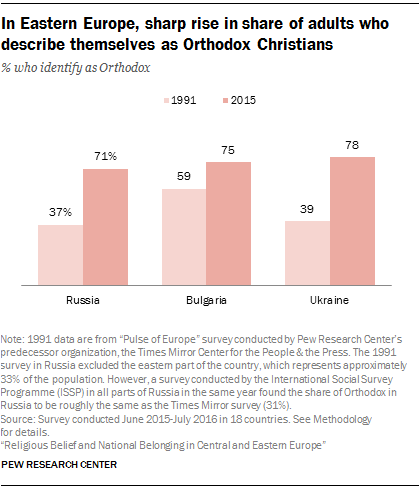

1  Shares of Orthodox Christians have risen sharply across the region, while shares of Catholics have declined. The percentage of Russians who identify as Orthodox Christians has risen substantially since the end of the USSR, from 37% in 1991 to 71% in the new survey. Consequently, the share of Russians who describe their religious identity as atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular” has fallen. And the trend is not limited to Russia. Similar patterns are evident in Ukraine and Bulgaria. At the same time, historically Catholic countries in Central and Eastern Europe have undergone a shift in the opposite direction: The Catholic share of the population in Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic has declined at least modestly since 1991.

Shares of Orthodox Christians have risen sharply across the region, while shares of Catholics have declined. The percentage of Russians who identify as Orthodox Christians has risen substantially since the end of the USSR, from 37% in 1991 to 71% in the new survey. Consequently, the share of Russians who describe their religious identity as atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular” has fallen. And the trend is not limited to Russia. Similar patterns are evident in Ukraine and Bulgaria. At the same time, historically Catholic countries in Central and Eastern Europe have undergone a shift in the opposite direction: The Catholic share of the population in Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic has declined at least modestly since 1991.

2 Orthodox Christians are less religiously observant than Catholics. The rise in Orthodox Christian identity has not been accompanied by high levels of church attendance. Relatively few Orthodox Christians in the region say they attend religious services at least weekly, including just 6% in Russia. Catholics in Central and Eastern Europe, by contrast, are considerably more likely to go to church weekly. For instance, 45% of Polish Catholics describe themselves as weekly Mass attenders.

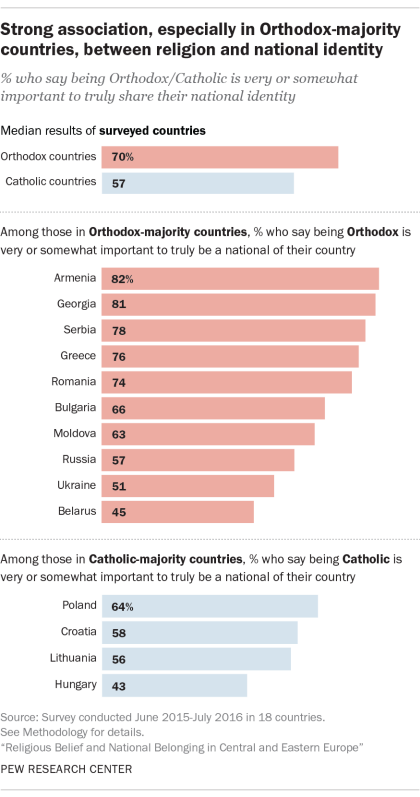

3 In Orthodox countries, there is a strong association between religion and national identity. While Catholics are more religiously observant than Orthodox Christians in the region, there tends to be a stronger link between religious identity and national identity in countries where Orthodox Christians make up a majority. A median of 70% in the 10 Orthodox-majority countries surveyed say that being Orthodox is “very” or “somewhat” important to truly sharing their national identity (e.g., to being “truly Greek”), while fewer in the four Catholic-majority countries surveyed (median of 57%) say the same about being Catholic. A similar pattern is seen on a question in the survey about cultural superiority: 69% of adults in Orthodox-majority Russia, for example, agree with the statement, “Our people are not perfect, but our culture is superior to others,” compared with 46% of adults in Catholic-majority Hungary.

3 In Orthodox countries, there is a strong association between religion and national identity. While Catholics are more religiously observant than Orthodox Christians in the region, there tends to be a stronger link between religious identity and national identity in countries where Orthodox Christians make up a majority. A median of 70% in the 10 Orthodox-majority countries surveyed say that being Orthodox is “very” or “somewhat” important to truly sharing their national identity (e.g., to being “truly Greek”), while fewer in the four Catholic-majority countries surveyed (median of 57%) say the same about being Catholic. A similar pattern is seen on a question in the survey about cultural superiority: 69% of adults in Orthodox-majority Russia, for example, agree with the statement, “Our people are not perfect, but our culture is superior to others,” compared with 46% of adults in Catholic-majority Hungary.

4 More people in Orthodox-majority countries than Catholic-majority countries support church-state ties. For many people, the connection between religion and nation extends to supporting close ties between church and state – in stark contrast with the situation during the Soviet era. Roughly a third or more of respondents in every Orthodox-majority country surveyed say government policies should support the spread of religious values and beliefs in their country, and even bigger shares in most of these places say their national Orthodox church should receive financial support from the government. In Catholic-majority countries in the region, fewer people generally say the government should promote religion or fund the Catholic Church.

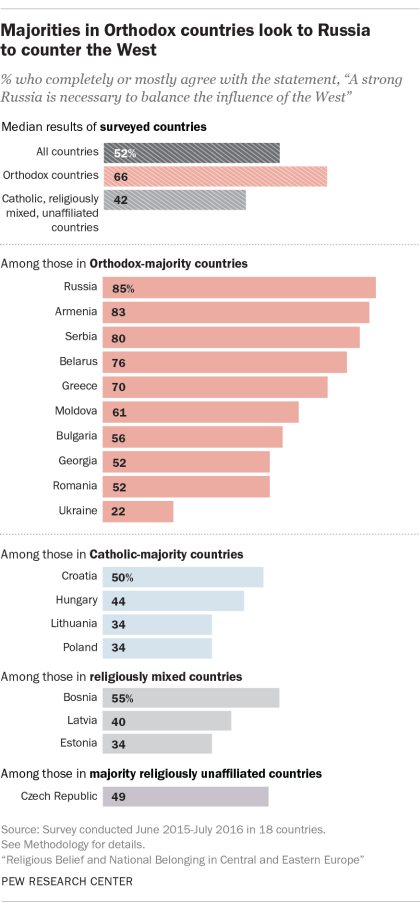

5  In Orthodox-majority countries, many people look to Russian leadership. Orthodox Christians in Central and Eastern Europe – and not just Russian Orthodox Christians – are more likely than others to favor Russian leadership in the region. For example, more people in Orthodox-majority countries than in Catholic-majority countries look to Russia as a counterbalance to Western influence. In addition, those in Orthodox-majority countries tend to take the position that Russia should protect ethnic Russians outside of Russia; about three-quarters of Romanians (74%) and seven-in-ten Moldovans (70%), for example, say Russia has this responsibility.

In Orthodox-majority countries, many people look to Russian leadership. Orthodox Christians in Central and Eastern Europe – and not just Russian Orthodox Christians – are more likely than others to favor Russian leadership in the region. For example, more people in Orthodox-majority countries than in Catholic-majority countries look to Russia as a counterbalance to Western influence. In addition, those in Orthodox-majority countries tend to take the position that Russia should protect ethnic Russians outside of Russia; about three-quarters of Romanians (74%) and seven-in-ten Moldovans (70%), for example, say Russia has this responsibility.

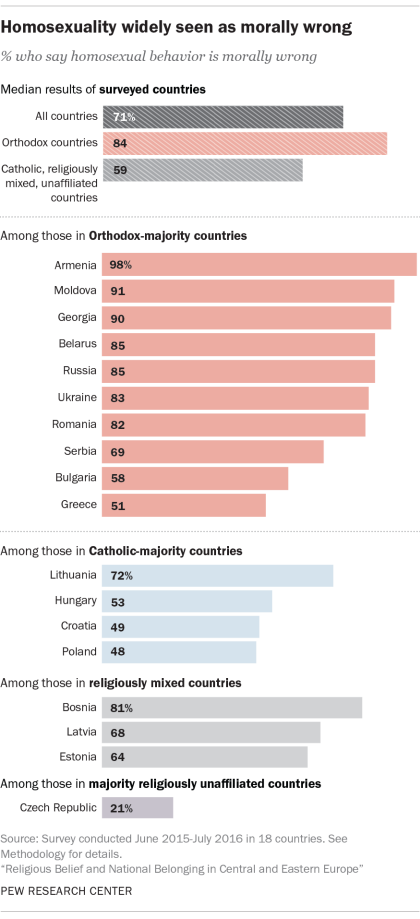

6  Conservative social views prevail, especially in Orthodox-majority countries. For many people in these countries, “traditional values” are socially conservative ones. Overwhelming shares of respondents in many of the countries surveyed say homosexuality should not be accepted by society, with people in Orthodox-majority countries especially likely to take this position. Orthodox-majority populations also are more likely than others to say abortion should be mostly or entirely illegal and to hold more conservative views on gender norms, such as saying that wives should always obey their husbands.

Conservative social views prevail, especially in Orthodox-majority countries. For many people in these countries, “traditional values” are socially conservative ones. Overwhelming shares of respondents in many of the countries surveyed say homosexuality should not be accepted by society, with people in Orthodox-majority countries especially likely to take this position. Orthodox-majority populations also are more likely than others to say abortion should be mostly or entirely illegal and to hold more conservative views on gender norms, such as saying that wives should always obey their husbands.

7 Nostalgia for the USSR is common. In several former Soviet republics, there is a robust strain of nostalgia for the USSR. In Armenia (79%) and Moldova (70%) – in addition to Russia (69%) – substantial majorities say the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 was a bad thing for their country, while 54% of adults in Belarus take this position. Even in Ukraine, where an armed conflict with pro-Russian separatists continues, about one-third (34%) of the public feels this way. In some of these countries, people also are more likely to rate the historical legacy of Josef Stalin’s leadership (1924 to 1953) more positively than that of the last Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, whose policies helped bring an end to the USSR.

8 There is mixed support for democracy. Even though democratic ideals and market economies quickly spread across the region following the fall of the Iron Curtain, Central and Eastern Europeans have not uniformly embraced democracy as the best form of government. While the prevailing view in most of the countries surveyed is that democracy is preferable to any other form of government, only in two countries – Greece (77%) and Lithuania (64%) – do clear majorities say this. Substantial shares in many countries say either that a nondemocratic government can be preferable in some circumstances, or that the type of government in their country does not matter to someone like them.

9 There is some hesitation about accepting Muslims and low acceptance of Roma. Orthodox Christians and Catholics are broadly accepting of one another – even, in most cases, as family members. In addition, most followers of both Christian traditions are willing to accept Jews as fellow citizens and neighbors. But Catholics are less willing than Orthodox Christians to say they would accept Muslims in these contexts. And people in the region are widely hesitant to accept the ethnic Roma population as fellow citizens, neighbors or family members.