Millions of people have migrated from their homes to other countries in recent years. Some migrants have moved voluntarily, seeking economic opportunities. Others have been forced from their homes by political turmoil, persecution or war and have left their countries to seek asylum elsewhere.

To mark International Migrants Day this Sunday, here are our key findings about international migration trends.

How many international migrants are there? Where are they from? Where do they live?

If all of the world’s international migrants (people living in a country that is different from their country or territory of birth) lived in a single country, it would be the world’s fifth largest, with around 244 million people. Overall, international migrants make up 3.3% of the world’s population today.

However, international migrants do not live in one country. Instead, they are dispersed across the world, with most having moved from middle-income to high-income countries. Top origins of international migrants include India (15.6 million), Mexico (12.3 million), Russia (10.6 million), China (9.5 million) and Bangladesh (7.2 million).

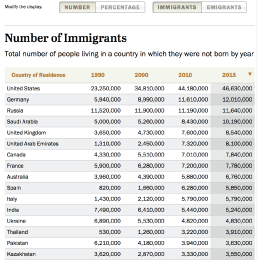

Among destination countries, the U.S. has more international migrants than any other country. It is home to about one-in-five international migrants (46.6 million). Other top destinations of migrants include Germany (12.0 million), Russia (11.6 million), Saudi Arabia (10.2 million) and the United Kingdom (8.5 million).

But absolute numbers don’t tell the whole migration story. For example, while the U.S. has the most immigrants in the world, only 14% of the country’s population is foreign born. This immigrant share is considerably lower than that in several Persian Gulf countries such as the United Arab Emirates, Qatar and Kuwait, where three-in-four or more people are international migrants. Moreover, top destination countries like Australia (28% foreign born) and Canada (22% foreign born) have much larger immigrant shares of their total population than the U.S.

Is international migration increasing?

It has increased substantially in terms of absolute numbers, but less so as a share of the world’s current population. The absolute number of international migrants has grown considerably over the past 50 years, from about 79 million in 1960 to nearly 250 million in 2015, a 200% increase. So by population size, there are far more international migrants today.

But the world’s population has also grown during that time, rising nearly 150% from about 3 billion to 7.3 billion. As a result, the share of the world’s population living outside their countries of birth has increased some during the past 50 or so years. In 1960, 2.6% of the world’s population did not live in their birth countries. In 2015, that share was 3.3%. As a share of the world’s population, the 0.7-percentage-point increase in the world’s migrant share is hardly insignificant. Nonetheless, the vast majority (nearly 97%) of the world’s population has not moved across international borders.

What have been some of the major pathways for international migration?

![]() The impact of migration has been large for counties that are part of some of the world’s most-used migrant corridors, particularly when it comes to pathways between a single origin country and a single destination country.

The impact of migration has been large for counties that are part of some of the world’s most-used migrant corridors, particularly when it comes to pathways between a single origin country and a single destination country.

For example, the Mexico-U.S. migration corridor has been one of the world’s most heavily traveled in recent decades. Today, about 12 million people born in Mexico are living in the U.S. This number has declined in recent years as net flows have reversed, with more Mexican immigrants leaving the U.S. than entering it. Also, the number of unauthorized Mexican immigrants in the U.S. has declined by 1 million between 2007 and 2014, even as the total number of unauthorized immigrants has stabilized at about 11.1 million.

While migration of Mexicans to the U.S. has been decreasing, Mexico is an important transit country for other U.S.-bound Latin Americans. U.S. border apprehensions of families and unaccompanied children have more than doubled between fiscal years 2015 and 2016, with most coming from El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras. A rising number of Cubans have also entered the U.S. via Mexico.

As of 2015, nearly 3.5 million Indians lived in the UAE, the world’s second-largest migration corridor. Unlike the Mexico-U.S. corridor, the number of Indians living in the UAE and other Persian Gulf countries has increased substantially during the past decade, from 2 million in 1990 to more than 8 million in 2015. Most have migrated for economic opportunities in these oil-rich countries.

The Middle East has the fastest-growing migrant population. When counting both international migrants and displaced migrants within their own countries (internally displaced persons), the number of migrants in the Middle East doubled during the past decade, from 25 million in 2005 to 54 million in 2015.

How many among the world’s migrants are refugees? Are they increasing in number?

Refugees are persons who cross international borders to seek protection from persecution, war and violence. Their total number has also increased from 50 years ago. Not including Palestinian refugees, there were about 1.7 million refugees worldwide in 1960, and about 16 million in 2015, according to United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. The number of refugees in 2015, however, is slightly less than the early 1990s following the fall of the Berlin Wall. As of 2015, refugees account for only about 8% of all international migrants.

Refugees are persons who cross international borders to seek protection from persecution, war and violence. Their total number has also increased from 50 years ago. Not including Palestinian refugees, there were about 1.7 million refugees worldwide in 1960, and about 16 million in 2015, according to United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. The number of refugees in 2015, however, is slightly less than the early 1990s following the fall of the Berlin Wall. As of 2015, refugees account for only about 8% of all international migrants.

Refugees are a subset of displaced persons worldwide. The latest UN estimates suggest that more than 60 million, or nearly 1 in 100 people worldwide, are forcibly displaced from their homes, the highest number and share of the world’s population since World War II. As of 2015, nearly two-thirds (63%) of the world’s displaced population still lived in their birth countries.

The Syrian conflict has dramatically increased the number of displaced people since the start of the Syrian conflict in 2011. About one-fifth of the world’s displaced, or 12.5 million, were born in Syria. Colombia, meanwhile, has more displaced people than any other country: nearly 7 million, most of whom are internally displaced because of the country’s decades-long conflict.

How many refugees are entering Europe and the U.S.?

Europe has also experienced its own refugee crisis as a destination for Syrians, Afghans, Iraqis and others escaping violence in their countries, with nearly 1.3 million refugees applying for asylum in the European Union, Norway and Switzerland in 2015. The EU struck a deal with Turkey in March 2016 to limit migrants coming through that country. Although that deal has largely halted migration from Turkey to Greece, Italy is on track to receive a record number of refugees this year. Meanwhile, European countries continue to work through a million or more asylum applications, including tens of thousands from unaccompanied minors.

Europe has also experienced its own refugee crisis as a destination for Syrians, Afghans, Iraqis and others escaping violence in their countries, with nearly 1.3 million refugees applying for asylum in the European Union, Norway and Switzerland in 2015. The EU struck a deal with Turkey in March 2016 to limit migrants coming through that country. Although that deal has largely halted migration from Turkey to Greece, Italy is on track to receive a record number of refugees this year. Meanwhile, European countries continue to work through a million or more asylum applications, including tens of thousands from unaccompanied minors.

In fiscal 2016, which ended Sept. 30, the U.S. resettled nearly 85,000 refugees within its borders, the most since 1999. As in Europe, there has been much discussion in the U.S. about which refugees should be admitted, both in terms of their origins and their religious affiliations. The U.S. has seen a shift in the origins of refugees, with most in recent years coming from Asia, Africa and the Middle East. During the 1990s, most were from Europe. At the same time, a record number of U.S. refugees in fiscal 2016 were Muslim, with most coming from Syria and Somalia. Refugees are resettled all over the U.S., but more than half (54%) were resettled in just 10 states.

In what ways does international migration impact countries?

Migration alters many things in origin and destination countries, but the international flow of money and demographic changes in host nations are some of the most noticeable.

Migration alters many things in origin and destination countries, but the international flow of money and demographic changes in host nations are some of the most noticeable.

As immigrants make money, they send some back to relatives in their home countries. These remittances have grown to nearly $600 billion worldwide in 2015. For some countries, remittances are an economic lifeline. For example, about a quarter or more of Central Asian countries’ gross domestic product is tied to remittances.

Migrants also alter the demographics of their destination countries. Between 1965 and 2015, 59 million people immigrated to the U.S. Factoring in their children and their children’s children, the population of the U.S. is 72 million higher than it would have been had this level of immigration not occurred. In the same way, immigration is expected to be a major contributor to the growth of the U.S. population for the next 50 years, increasing the total number of people to a projected 441 million. If no additional immigrants were to enter the U.S. from 2015 forward, the country’s population would be about 338 million in 2065 – about the same as it is today.

More recently, several European countries have seen their immigrant shares jump by 1 percentage point in less than a year as hundreds of thousands of refugees from Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq and other countries entered the Continent in 2015. As a point of comparison, the immigrant share of the U.S. population increased by about 1 percentage point over a decade, rising from 13% in 2005 to about 14% in 2015.

There can also be an impact on migrants’ countries of origin when they cross international borders, especially if they move in large numbers. In 2015, nine countries had 20% or more of their birth populations living in a different country. Large-scale emigration can have significant impacts on the demographics of nations. For example, Albania has seen many of its young adults leave for opportunities elsewhere. By comparison, emigration has been more common among highly educated groups in Trinidad and Tobago. In some instances, out-migration among particular groups can exacerbate population aging and leave significant skill gaps within these source countries.

How do Americans and Europeans view immigrants?

Americans’ opinions of immigrants have changed in recent years. In a new Pew Research Center survey, about six-in-ten U.S. adults (63%) say that immigrants strengthen the country through their hard work and talents. By contrast, about one-fourth (27%) say immigrants are a burden to the U.S. by taking jobs, housing and health care. The U.S. public’s views of immigrants have largely reversed since the 1990s, when 63% said immigrants were a burden for the country and just under a third (31%) said immigrants strengthened the nation. Some groups of Americans hold more positive views of immigrants than others. For example, Democrats recently have been more likely than Republicans to say immigrants in the U.S. are a strength for the country. Also, younger age groups tend to hold more positive views than older generations.

Americans’ opinions of immigrants have changed in recent years. In a new Pew Research Center survey, about six-in-ten U.S. adults (63%) say that immigrants strengthen the country through their hard work and talents. By contrast, about one-fourth (27%) say immigrants are a burden to the U.S. by taking jobs, housing and health care. The U.S. public’s views of immigrants have largely reversed since the 1990s, when 63% said immigrants were a burden for the country and just under a third (31%) said immigrants strengthened the nation. Some groups of Americans hold more positive views of immigrants than others. For example, Democrats recently have been more likely than Republicans to say immigrants in the U.S. are a strength for the country. Also, younger age groups tend to hold more positive views than older generations.

Immigration was a top issue in the 2016 U.S. presidential campaign, and the divide between Democrats and Republicans on immigration issues has been stark. In another survey by the Center conducted in early August, nearly eight-in-ten voters who supported President-elect Donald Trump favored building a wall along the U.S.-Mexican border, while only one-in-ten voters who supported Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton favored it. Nonetheless, the majority (60%) of Trump supporters said that undocumented immigrants should be allowed to stay in the country provided they met certain requirements. By comparison, nearly all (95%) of Clinton supporters said the same.

In Europe, the recent surge of refugees has made some Europeans wary of the immigration situation in their countries. In eight of 10 European nations surveyed in spring, half or more adults in those countries said incoming refugees increased the likelihood of terrorism in their countries. Similarly, half or more adults in five of the 10 countries surveyed said that refugees would have a negative economic impact on their countries, taking jobs and social benefits.

As the influx of different races, ethnic groups and nationalities changes the face of Europe, few Europeans say that growing diversity makes their country a better place to live. In none of the 10 nations surveyed did a majority see increasing diversity as a positive. The same survey found Europeans sharply divided about whether refugees leaving Iraq and Syria were a major threat to their countries.