Donald Trump’s proposal for a constitutional amendment imposing term limits on members of Congress has drawn new attention to an issue that, after a burst of popularity in the early and mid-1990s, had been mostly dormant for nearly two decades.

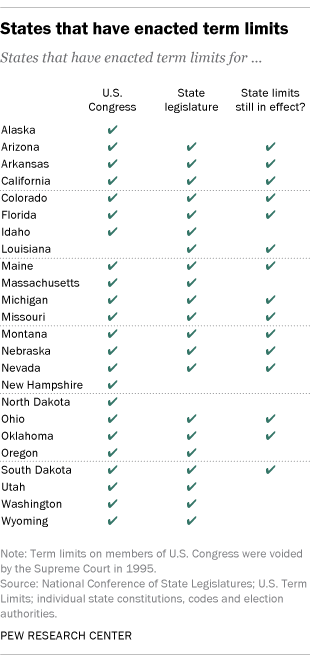

By spring of 1995, 23 states had enacted laws or amended their state constitutions (in all but two cases by citizen initiative) to limit the terms of their federal senators and representatives, and congressional term limits enjoyed wide popular support.

By spring of 1995, 23 states had enacted laws or amended their state constitutions (in all but two cases by citizen initiative) to limit the terms of their federal senators and representatives, and congressional term limits enjoyed wide popular support.

But two events that year took most of the steam out of the term-limits movement. In March, the House of Representatives turned down a term-limits constitutional amendment, coming nowhere close to the two-thirds vote needed. And in May, the Supreme Court ruled that such an amendment was the only way to impose term limits, voiding all those state measures insofar as they applied to Congress. (Another term-limits amendment barely cleared a majority in a 1997 House vote, and the issue hasn’t been acted upon since.)

However, the Supreme Court’s ruling did not touch limits on state legislators that were enacted alongside the congressional ones. Today, 15 states limit how many terms their lawmakers can serve: Six impose lifetime limits of varying lengths, while nine require lawmakers to sit out after a given number of terms before they can run again. (In four other states, voter-imposed limits have been thrown out by state supreme courts on various substantive and procedural grounds; in Utah and Idaho, legislatures repealed term-limits laws directly.)

While relatively few states place term limits on their legislators, most of them (36) limit how many terms their governors can serve. (In fact, 28 of those gubernatorial limits predate the 1990s term-limits movement). Today, 27 states limit their governors to two consecutive terms but allow them to run again after four or eight years; eight set a lifetime limit of two terms; and Virginia, uniquely, bars governors from succeeding themselves but doesn’t limit the total number of nonconsecutive terms they may serve (though no one has done so since Mills Godwin served a second nonconsecutive term in the mid-1970s). In four other states, gubernatorial limits enacted in the early 1990s were overturned or repealed along with the legislative limits.

While relatively few states place term limits on their legislators, most of them (36) limit how many terms their governors can serve. (In fact, 28 of those gubernatorial limits predate the 1990s term-limits movement). Today, 27 states limit their governors to two consecutive terms but allow them to run again after four or eight years; eight set a lifetime limit of two terms; and Virginia, uniquely, bars governors from succeeding themselves but doesn’t limit the total number of nonconsecutive terms they may serve (though no one has done so since Mills Godwin served a second nonconsecutive term in the mid-1970s). In four other states, gubernatorial limits enacted in the early 1990s were overturned or repealed along with the legislative limits.

After years in which other issues (such as flag desecration and same-sex marriage) have preoccupied Congress’ would-be amenders, there’s been a modest increase in the number of term-limits amendments introduced, though none have come close to a floor vote.

Many political scientists and others who’ve studied the issue have expressed doubt that term limits would bring new and different types of lawmakers into office, and some argue that limits tend to shift power away from legislatures and toward executives and other political actors. Nonetheless, the idea of term limits remains popular with Americans of all partisan stripes and age groups.

In a Gallup poll from January 2013 – the most recent national survey on the subject that we could find – 75% said they would vote for a term-limits law if given the chance. In mid-2014, when Gallup asked an open-ended question about how best to fix Congress, 11% cited term limits as their first choice (behind “replace all members” and “work together”).