As the long presidential campaign winds down, GOP nominee Donald Trump’s claims that the process is “rigged” against him – and suggestions that he might not accept the result as legitimate if he loses – seem to have struck a chord with his supporters. In a recent Pew Research Center survey, 56% of Trump voters said they have little or no confidence that the election will be “open and fair,” compared with 11% of Hillary Clinton backers. Among those who say they strongly back Trump, nearly two-thirds (63%) say they have little or no confidence that the election will be fair.

As the long presidential campaign winds down, GOP nominee Donald Trump’s claims that the process is “rigged” against him – and suggestions that he might not accept the result as legitimate if he loses – seem to have struck a chord with his supporters. In a recent Pew Research Center survey, 56% of Trump voters said they have little or no confidence that the election will be “open and fair,” compared with 11% of Hillary Clinton backers. Among those who say they strongly back Trump, nearly two-thirds (63%) say they have little or no confidence that the election will be fair.

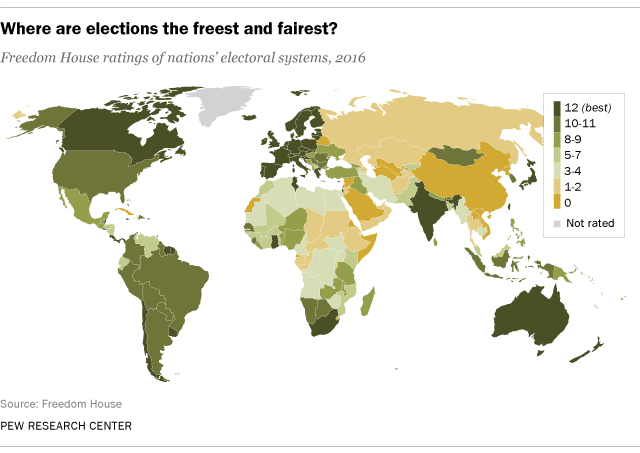

Given that level of skepticism, it’s worth noting that the U.S. generally ranks highly on the overall freedom and fairness of its elections when compared with other countries, though not without some caveats.

Given that level of skepticism, it’s worth noting that the U.S. generally ranks highly on the overall freedom and fairness of its elections when compared with other countries, though not without some caveats.

Freedom House, a nongovernmental organization (though it receives funding from the U.S. government), has ranked nations on political and civil rights for more than 40 years. In its most recent report, Freedom House gave the U.S. electoral process 11 out of 12 possible points on its “electoral process” scale – the same rating the nation has had since 2007 (when its score was raised from a 10).

The electoral process scale is one of seven that go into Freedom House’s overall ratings of countries as free, partly free or not free. It covers three major areas: whether the head of government or other chief national authority is chosen through free and fair elections; whether national legislators are chosen through free and fair elections; and whether a country’s electoral laws and framework are fair. Among the things that go into making elections “free and fair”: “Is the vote count transparent, and is it reported honestly with the official results made public?”

Of the 195 sovereign countries Freedom House ranked this year (using 2015 data), 61 scored 12 out of 12 on the group’s electoral process scale – among them Australia, Canada, Japan and the UK. Besides the U.S., 16 other countries received 11 points out of 12. Freedom House didn’t detail where the U.S. fell short, but commented in its report that “… its elections and legislative process have suffered from an increasingly intricate system of gerrymandering and undue interference by wealthy individuals and special interests.”

While well-known and frequently cited by media and academics, the Freedom House rankings aren’t the only cross-national measures of democracy. The Economist Intelligence Unit, an analytics and forecasting business affiliated with the British newsmagazine, has produced its “Democracy Index” every year or two since 2006. This year’s version gives the U.S. 9.17 out of 10 points in the “electoral process and pluralism” category, one of 21 countries to receive that score (some of the others: Cape Verde, Denmark, El Salvador and Japan). Besides whether elections for the head of government, national legislature and municipalities are free and fair, the EIU’s electoral process/pluralism measure also covers voting restrictions, campaign finance and the orderly transfer of power.

Six countries – Finland, Iceland, Luxembourg, New Zealand, Norway and Uruguay – received the highest possible scores on the EIU’s electoral process/pluralism scale. The EIU expressed no concerns about the integrity of U.S. elections, but commented that the U.S. electoral structure “means that participation is, in effect, restricted to a duopoly of parties, the Democrats and the Republicans. Nevertheless, respect for the constitution and democratic values are deeply entrenched by centuries of democratic practice.”

Six countries – Finland, Iceland, Luxembourg, New Zealand, Norway and Uruguay – received the highest possible scores on the EIU’s electoral process/pluralism scale. The EIU expressed no concerns about the integrity of U.S. elections, but commented that the U.S. electoral structure “means that participation is, in effect, restricted to a duopoly of parties, the Democrats and the Republicans. Nevertheless, respect for the constitution and democratic values are deeply entrenched by centuries of democratic practice.”

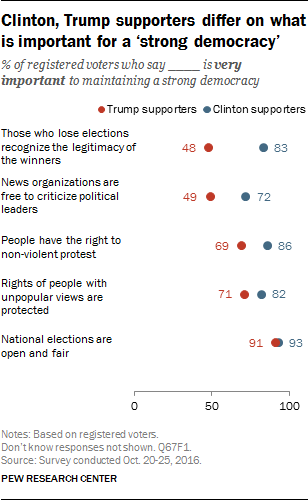

Despite that assessment, there are stark political divides on certain democratic norms. In the Pew Research Center survey, 83% of Clinton supporters – but just 48% of Trump supporters – said it was “very important” to a strong democracy that those who lose elections recognize the legitimacy of the winners. And while 72% of Clinton backers said it was very important that the news media be free to criticize political leaders, only 49% of Trump backers said so.