Many Americans are wary of the prospect of implanting a computer chip in their brains to improve their mental abilities or adding synthetic blood to their veins to make them stronger and faster, according to a major new Pew Research Center survey gauging the public’s views on technologies that could enhance human abilities. And this is particularly true of those who are highly religious.

Many Americans are wary of the prospect of implanting a computer chip in their brains to improve their mental abilities or adding synthetic blood to their veins to make them stronger and faster, according to a major new Pew Research Center survey gauging the public’s views on technologies that could enhance human abilities. And this is particularly true of those who are highly religious.

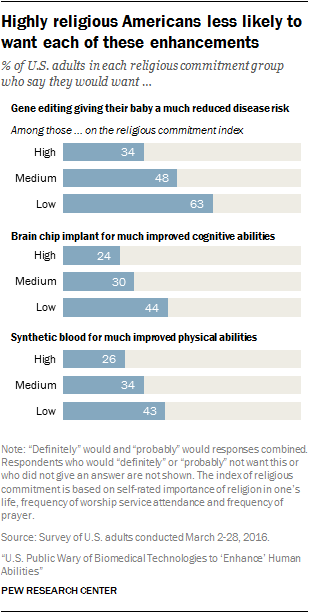

For instance, a majority of highly religious Americans (based on an index of common religious measures) say they would not want to use a potential gene-editing technology that would give their baby a much reduced risk of disease (64%), while almost the same share of U.S. adults with “low” religious commitment would want to use such a technology (63%).

Similar patterns exist on questions about whether people would want to enhance themselves by implanting a computer chip in their brains or by having synthetic blood transfusions. Not only are highly religious Americans less open to healthy people using these potential technologies, but they are more likely to cite a moral opposition to them – and even to connect them directly to religious themes.

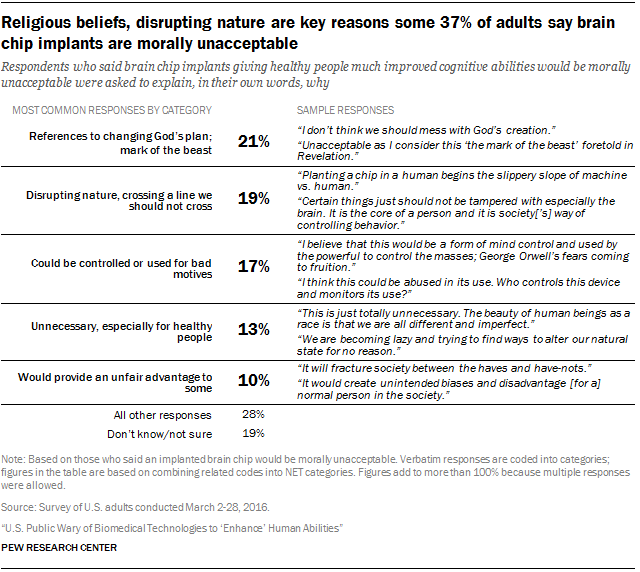

Case in point: Many people who said these technologies would be morally unacceptable explained their position with references to “changing God’s plan.” In the case of a computer chip in the brain, some opponents connected this idea to the “mark of the beast,” a reference involving Satan in the Bible’s book of Revelation.

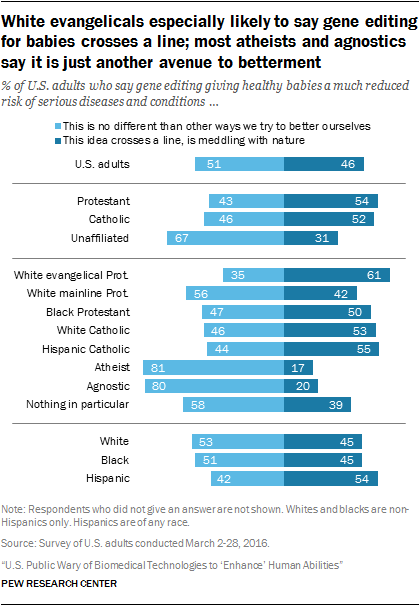

In addition to gaps based on levels of religious commitment, members of certain religious groups are more apt than others to express reservations about the potential future human enhancement technologies that were mentioned in the survey. For example, white evangelical Protestants are more likely than Americans overall (64% vs. 49%) to say using synthetic blood to give healthy people greater speed, strength and stamina would be crossing a line and “meddling with nature.”

Some theologians and religious thinkers have started to consider the implications of these potential enhancements, and views among evangelicals overall may line up with the teachings of their tradition. “I think a lot of evangelical leaders and pastors will see [enhancement technologies] as unwise and will call on people to avoid it,” says Todd Daly, an associate professor of theology and ethics at Urbana Theological Seminary. (Daly’s comments come from a background essay that explores the science and ethics behind these technologies, with a special focus on the views of major religious traditions as they grapple with the potential of human enhancement to change society.)

Some theologians and religious thinkers have started to consider the implications of these potential enhancements, and views among evangelicals overall may line up with the teachings of their tradition. “I think a lot of evangelical leaders and pastors will see [enhancement technologies] as unwise and will call on people to avoid it,” says Todd Daly, an associate professor of theology and ethics at Urbana Theological Seminary. (Daly’s comments come from a background essay that explores the science and ethics behind these technologies, with a special focus on the views of major religious traditions as they grapple with the potential of human enhancement to change society.)

U.S. Catholics are somewhat less wary of potential human enhancements than are evangelicals. Still, most say they would not want brain chips or synthetic blood, and many see these things as morally questionable or problematic. While the Catholic Church actively supports medical advancements, “the dividing line for the church is the line between therapy and enhancement,” says Christian Brugger, professor of moral theology at St. John Vianney Theological Seminary, meaning that procedures intended purely for enhancement would be unacceptable.

Similar to Catholics, white mainline Protestants are ambivalent toward these issues, but they are more open to potential human enhancements in some ways. For instance, a majority (56%) of white mainline Protestants say gene editing for babies would be no different than other ways humans try to better themselves. Fewer (42%) say they are crossing a line and meddling with nature. “I think [mainline churches] will see much of this for what it is: an effort to take advantage of these new technologies to help improve human life,” says Ted Peters, professor of systematic theology at Pacific Lutheran Theological Seminary.

Perhaps some of the most striking findings on these issues, however, involve those who are not affiliated with any religion. Self-identified atheists and agnostics, in particular, are by far the most open to using these technologies, and easily the least likely to see them as morally troubling. For instance, three-quarters of atheists say they would want gene editing for their babies to reduce the risk of disease, and many atheists say they would want a brain chip (58%) and synthetic blood (54%) to enhance their minds and bodies.

Atheists and agnostics overwhelmingly see these examples as no different from other efforts at human advancement, while religiously affiliated Americans – and even those who are unaffiliated but describe their religion as “nothing in particular” – are far more likely to say these technologies would cross a line and meddle with nature.

Note: This post was revised Nov. 2, 2016, to include updated data in categorizing white Protestants into the “white evangelical Protestant” and “white mainline Protestant” categories. Originally, the post relied partly on data from a previous wave of the American Trends Panel to make these categorizations.