The U.S. is projected to have no racial or ethnic group as its majority within the next several decades, but that day apparently is already here for the nation’s youngest children, according to new Census Bureau population estimates.

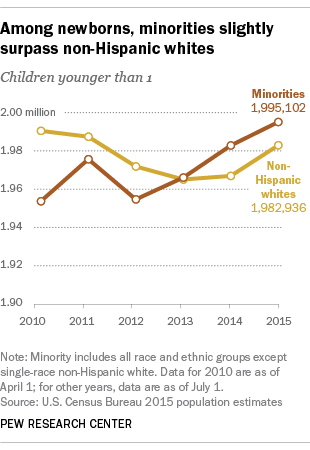

The bureau’s estimates for July 1, 2015, released today, say that just over half – 50.2% – of U.S. babies younger than 1 year old were racial or ethnic minorities. In sheer numbers, there were 1,995,102 minority babies compared with 1,982,936 non-Hispanic white infants, according to the census estimates. The new estimates also indicate that this crossover occurred in 2013, so the pattern seems well established.

The bureau’s estimates for July 1, 2015, released today, say that just over half – 50.2% – of U.S. babies younger than 1 year old were racial or ethnic minorities. In sheer numbers, there were 1,995,102 minority babies compared with 1,982,936 non-Hispanic white infants, according to the census estimates. The new estimates also indicate that this crossover occurred in 2013, so the pattern seems well established.

Pinpointing the exact year when minorities outnumbered non-Hispanic whites among newborns has been difficult. The change among newborns is part of a projected U.S. demographic shift from a majority-white nation to one with no racial or ethnic majority group that is based on long-running immigration and birth trends. But changes in short-term immigration flows and in fertility patterns can delay those long-term shifts.

In 2012, the Census Bureau declared that in 2011 most children younger than age 1 were minorities. The bureau’s population estimates also indicated minorities were the majority among babies in 2012. But when the bureau released its 2013 estimates, it revised those earlier estimates to indicate that, in all three years, newborn non-Hispanic whites still outnumbered minorities, by a small margin.

The estimates released this year included revised 2013 estimates that now say there were about a thousand more minority babies than non-Hispanic white babies that year, a tiny difference given that each group numbered more than 1.9 million. In 2014, minority babies outnumbered white babies by about 16,000, and in 2015 the difference was about 12,000, according to the agency’s estimates.

The Census Bureau frequently revises its past population estimates to account for newly available data. Birth data is a special problem: In estimating the number and characteristics of newborns, the agency relies in part on birth certificate information from the National Center for Health Statistics that is two years out of date.

One reason that the bureau had to delay its claim of a majority-minority newborn population may have been a sharp falloff in births and birth rates after the onset of the Great Recession in 2007. Birth rates declined most steeply for Hispanic and immigrant women.

The Census Bureau statistics indicate that demographic change is percolating upward through the nation’s age groups, starting with the youngest ones. In fact, the bureau estimates indicate that 50.3% of children younger than 5 were racial or ethnic minorities in 2015.

The Census Bureau statistics indicate that demographic change is percolating upward through the nation’s age groups, starting with the youngest ones. In fact, the bureau estimates indicate that 50.3% of children younger than 5 were racial or ethnic minorities in 2015.

In the total U.S. population, non-Hispanic whites will cease to be the majority group by 2044, according to Census Bureau projections, or by 2055, according to Pew Research Center projections.

Racial and ethnic minorities have accounted for most of the nation’s growth in recent decades. The non-Hispanic white population has grown too, but not as quickly. Minority populations have grown more rapidly in part because these groups are younger than whites and include a higher share of women in their prime child-bearing years. Some minority groups, especially Hispanics, have higher birthrates than do non-Hispanic whites. In addition, a rising number of babies are being born to couples where one parent is white and the other nonwhite.

While census estimates have shown a shift toward a majority-minority infant population, estimates about the race of mothers from another data source – the National Center for Health Statistics – do not. Its preliminary 2015 data indicate that 54% of births are to non-Hispanic white mothers, a similar share as in 2011, 2012, 2013 and 2014. However, the two agencies measure race differently. For example, the Census Bureau reports data about children of multiple races, while the National Center for Health Statistics changes mixed-race mothers into single-race mothers in publishing its data. And the Census Bureau uses available information about the father’s race or Hispanic origin, as well as the mother’s, to determine the baby’s race and ethnic categories, while the health-statistics center reports only the mother’s race and ethnic origin.