Donald Trump, the presumptive Republican presidential nominee, reportedly has begun vetting potential choices for vice president. And with less than a month to go in the Democrats’ primary season, either Hillary Clinton or Bernie Sanders (or possibly both) likely will start researching possible running mates – if they haven’t already.

Donald Trump, the presumptive Republican presidential nominee, reportedly has begun vetting potential choices for vice president. And with less than a month to go in the Democrats’ primary season, either Hillary Clinton or Bernie Sanders (or possibly both) likely will start researching possible running mates – if they haven’t already.

Presidential candidates get a lot of public scrutiny during the United States’ extended nominating process, but like dandelions or mushrooms after a spring shower, vice presidential candidates seem to pop up suddenly in the political chatter once a party settles on a presidential nominee. We wondered what sort of people have gotten picked for the second spot on national tickets. To find out, we took a ramble through vice presidential history since 1868 (the first post-Civil War election).

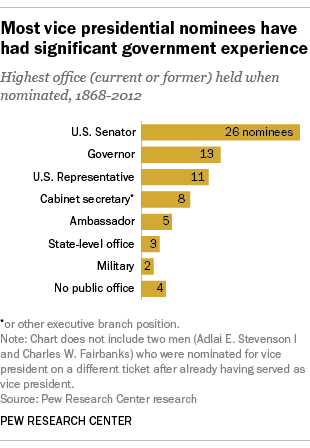

Of the 72 people since then who have been nominated for vice president on a major-party (or significant third-party) ticket, most have had a fair degree of political experience on the national, or at least state, level. A third (24) were U.S. senators at the time of their nomination; two more were former senators. Thirteen were current or former governors; 11 were current or former U.S. representatives, including two incumbent House speakers. Two nominees, in fact, had already served as vice president when they were chosen for another go with new presidential candidates: Adlai Stevenson I in 1900 and Charles W. Fairbanks in 1916. And one nominee, Democrat Thomas A. Hendricks, was on Samuel Tilden’s losing ticket in 1876 but won with Grover Cleveland eight years later, though he only served as vice president for nine months before dying in office.

Only six vice-presidential nominees had held no prior elective or high appointive office. Two were ex-military leaders, Air Force Gen. Curtis LeMay and Navy Adm. James Stockdale; both ran on losing third-party tickets (headed by George Wallace and Ross Perot, respectively). Only twice did the major parties nominate a vice president directly from the private sector: banker and shipbuilder Arthur Sewall (Democrats, 1896) and newspaper publisher Frank Knox (Republicans, 1936); both lost.

Until the mid-20th century, most presidential candidates had little or no input into the choice of their running mate. Vice presidents typically were picked by party bigwigs to bring geographic or ideological balance to the ticket, or to unify disparate wings of the party. On occasion, though, convention delegates stampeded toward a candidate of their own choosing, as in 1920 when they voted for Calvin Coolidge as Warren Harding’s running mate.

The relationship between presidential candidates and their running mates in this period was perhaps best, if unintentionally, captured by Rutherford B. Hayes, the GOP nominee in 1876. Upon being informed that the convention had picked Rep. William A. Wheeler of New York for the second spot, Hayes reportedly responded: “I am ashamed to say, who is Wheeler?”

That began to change in 1940, when Franklin D. Roosevelt sought and won nomination for an unprecedented third term – sidelining his own vice president, John Nance Garner, who had sought the nomination himself. Roosevelt picked Agriculture Secretary Henry A. Wallace to replace Garner. Although many at the Democratic convention opposed Wallace, Roosevelt threatened to decline the nomination unless he was chosen, and the delegates grudgingly went along. Since then, virtually all presidential nominees have chosen their running mates themselves. (Wallace, incidentally, was the last vice president to have held no prior elective office.)

Presidential nominees occasionally pick one of their defeated rivals to join their ticket. In 1980, for instance, Ronald Reagan selected George H.W. Bush, who had battled him throughout most of the primaries; as recently as 2008, Barack Obama chose then-Sen. Joe Biden, whose brief campaign had ended after the Iowa caucuses. But such moves don’t happen very often: By our count, only 18 of the 72 major vice-presidential nominees since 1868 had sought the presidency themselves in that cycle.

Not that several of them didn’t move into the White House eventually. Eight of the 31 men who have served as vice president since 1868 became president themselves – six by succession and two (Richard Nixon and George H.W. Bush) by election in their own right. Four other vice presidents were nominated for president later on but lost. FDR is the only person who, after having been a losing vice presidential candidate (in 1920), succeeded in winning the top job himself (in 1932).

The vice presidency long was considered, in the words of a Stevenson biographer, as “a final resting place for has-beens and never-wases.” But even if they didn’t become president or run for the job themselves, many vice presidential candidates have had meaningful political afterlives. Paul Ryan, to take the most recent example, was elected House speaker last fall, almost three years after he and Mitt Romney lost the 2012 election. Joe Lieberman, Al Gore’s running mate in 2000, remained in the Senate another 12 years. Five years before being appointed chief justice, Earl Warren was the bottom half of the infamous 1948 “Dewey Defeats Truman” ticket.