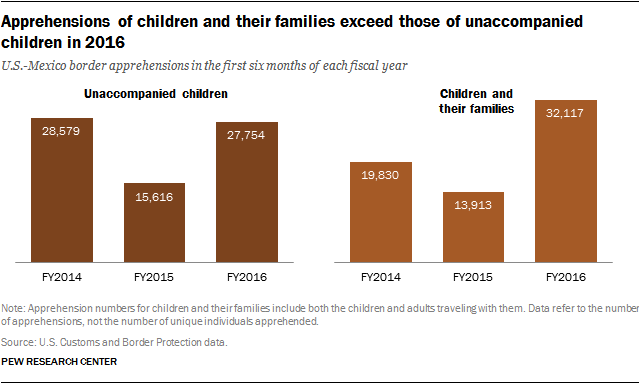

Apprehensions of children and their families at the U.S.-Mexico border since October 2015 have more than doubled from a year ago and now outnumber apprehensions of unaccompanied children, a figure that also increased this year, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of U.S. Customs and Border Protection data.

There were 32,117 apprehensions of family members – defined as children traveling with at least one parent or guardian – during the first six months of fiscal 2016 (October 2015 to March 2016). By comparison, apprehensions of unaccompanied children totaled 27,754 over the same period. The number of family apprehensions is more than double that of the previous year. The number of apprehensions of unaccompanied children shot up by 78%.

The apprehension of more families than unaccompanied children is a reversal from summer 2014, when thousands of children fled gang violence and poverty in Central America and migrated north to the U.S. without a parent or guardian. During the first six months of fiscal 2014, there were 19,830 apprehensions of children and their families, compared with 28,579 apprehensions of unaccompanied children.

It remains to be seen whether apprehensions of unaccompanied children or families will surge this summer and surpass the full-year apprehension totals from two years ago. This fiscal year, family and unaccompanied children apprehensions spiked in December 2015, and in January 2016 the Department of Homeland Security launched immigration raids targeting families. Since then, monthly border apprehensions have dropped below 2014 levels. For example, March 2016 apprehensions of children and their families (4,452) and unaccompanied children (4,240) are lower than in March 2014, when authorities apprehended 5,752 children and their families and 7,176 unaccompanied children.

Border apprehensions of children, considered an indicator of the flows of child migrants entering the U.S. illegally, dropped off steeply in fiscal 2015 as Mexico stepped up deportations of Central American children and the U.S. government launched public information campaigns in Central American countries to discourage children from making the trip north. The U.S. also sped up the processing of immigration court cases, but a large backlog in cases still exists.

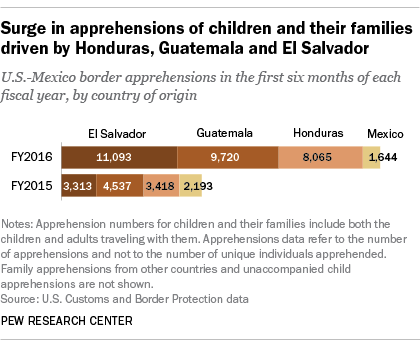

The surge in family apprehensions at the U.S.-Mexico border in 2016 is driven by migrants from El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras, who together make up 90% of these apprehensions so far this fiscal year. The number of family apprehensions from these Central American countries more than doubled in the first six months of fiscal 2016 over the same time period in 2015. Meanwhile, among Mexicans, family apprehensions decreased by 25% over the same period.

The surge in family apprehensions at the U.S.-Mexico border in 2016 is driven by migrants from El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras, who together make up 90% of these apprehensions so far this fiscal year. The number of family apprehensions from these Central American countries more than doubled in the first six months of fiscal 2016 over the same time period in 2015. Meanwhile, among Mexicans, family apprehensions decreased by 25% over the same period.

Apprehensions of unaccompanied children so far in 2016 are similar to the first six months of 2014. When looking at where unaccompanied children are from, there have been substantially more apprehensions among those from Guatemala (9,383) and El Salvador (7,914) than Honduras (4,224) during the first six months of fiscal 2016. In 2014, Honduras was the leader in the number of unaccompanied minors apprehended.

U.S. government officials have started to prepare for a possible increase in migration from Central America this summer. For example, the Department of Health and Human Services has requested additional contingency funding from Congress to shelter apprehended children. In addition, the governor of Texas extended the deployment of the state’s National Guard at the border with Mexico in December, which coincided with a spike that month in border apprehensions.

Roughly two-thirds of family apprehensions in this fiscal year have come at the U.S. Customs and Border Protection’s Rio Grande sector, located along the southernmost tip of Texas and bounded by Mexico and the Gulf of Mexico. (The sector accounted for a similar share of apprehensions during the first six months of fiscal 2014 and fiscal 2015.)

Note: This post and the text of the first chart have been updated to reflect the fact that the data refer to the number of apprehensions and not the number of unique individuals apprehended.