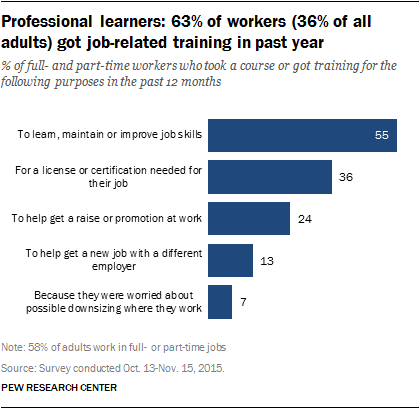

As automation looms and more and more jobs are being shaped to accommodate the tech-saturated “knowledge economy,” 63% of full- and part-time workers say they have taken steps in the past 12 months to upgrade their skills and knowledge.

As automation looms and more and more jobs are being shaped to accommodate the tech-saturated “knowledge economy,” 63% of full- and part-time workers say they have taken steps in the past 12 months to upgrade their skills and knowledge.

That is one of several key findings from a Pew Research Center survey conducted last fall to understand people’s motives for learning, both in professional and personal contexts. The Center then held a series of related focus groups in December, drawing insights from those in the Baltimore, Atlanta and St. Louis metro regions.

Here are some of the key themes that came out of those conversations about learning, work and a changing economy.

The Great Recession led to soul-searching and skills re-evaluation. A number of participants talked about how they took stock of their skill set and employability after the economic collapse that began in 2007-08. As a result, many pursued job-related training. More than half (55%) of those who did so sought to learn, maintain or improve job skills:

[In 2008] I saw everything going on around me with co-workers, neighbors, friends and asked myself, “Who’s coming after me and my job? How long are my skills going to last?” …. I did some research that was pretty comforting, but I try to spend a little time every couple of months now reassessing my status.

– Mid-career professional, Atlanta region

My friends and I just assume that what we do now will be obsolete in the next decade. That’s our reality. You always have to keep learning and improving.

– Millennial in starter job, St. Louis region

Indeed, many noted how technology had encroached on traditional human workplace activities, including sophisticated tasks:

I don’t know whether to laugh or cry when there are ads for all the things computers can do that used to require people [to perform].

– Baby Boomer skilled worker, Baltimore region

Those who aren’t trying to improve will get passed by. One compelling motivation for some is to stay nimble and keep learning in order to increase their worth for employers and in their own eyes:

You don’t want to stagnate in your learning and your position. My thinking is you have to have a hunger to learn, or else the people who do have that hunger are going to make you seem like you’re out of it – [you’re] besides the point.

– Middle-aged professional in St. Louis region

I want to be alert and keep my mind working and going. I don’t want to be somewhere stuck. I keep trying to learn more by challenging myself, thinking outside the box. Be creative, inspirational, that kind of thing. I would hate myself if I stopped trying to get better at what I do.

– Millennial in the music business, Atlanta region

Competition is coming from every direction, including globalization and new job entrants. Technology advances are only part of the story. People know jobs can be outsourced abroad or challenged by others in the local labor market:

Everything in life is getting more competitive and it starts with the job. There are people trying to get hired and get promoted. There are people trying to show how much they have learned and how much they have done – real resume builders. There are people who will work for less in other countries. [Expletive], I even compete with myself. I just started body building and I want to get better – and also beat the people working out in the gym around me.

– 30-something white-collar worker, St. Louis region

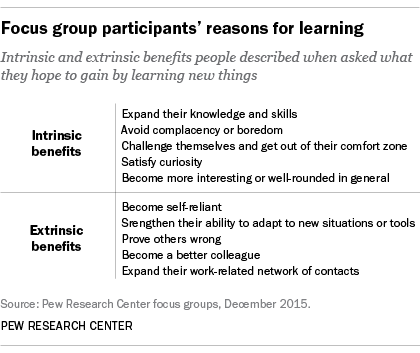

People have intrinsic and extrinsic reasons to keep learning. In addition to trying to stay employable, participants cited any number of reasons they have pursued new knowledge. Some were related to self-fulfillment:

People have intrinsic and extrinsic reasons to keep learning. In addition to trying to stay employable, participants cited any number of reasons they have pursued new knowledge. Some were related to self-fulfillment:

It’s so satisfying to master something and make yourself valuable to others. You know, [when it starts as] something that you never knew that you could do and then you learn you can do it, it’s like, ahhhh. I got it. There is no better feeling.

– Nonprofit worker, Baltimore region

One of the St. Louis region participants told of a time when he knew his organization needed better ways to do communications and outreach. So he taught himself how to be a desktop publisher and use social media for promotional purposes. Within a year, his efforts had yielded so much attention for the organization that it got a high-profile visit from an Obama administration official and local political leaders:

It makes me feel really good that I took the time and didn’t do it halfway. I gave it 100%. And they did not expect these results at all, so it really makes me feel important in that organization.

Another participant from the St. Louis region described how she feels it is important to keep on learning because so many people depend on her to make good choices:

I have to make so many decisions for my family and my work. I have to stay on top of research to make educated decisions for myself and the people in my life. My colleagues depend on me and my children depend on me.

To which another member of that group quickly added that he is dismayed watching people who don’t want to learn:

Sometimes I see people who don’t learn and [seem to feel], “Oh, yeah, I’ll accept it just like it is” as opposed to thinking, “I don’t know, what’s really behind that and I should find out more.” I watch the [people uninterested in learning] get into trouble and I think, “Oh, my God, that could’ve been me.” … And then I look at them and say, “[Expletive], you don’t want to know any more than that? You’ll be sorry.”

Sometimes people’s rationale for job-related learning is defiance. There are those whose motivation for learning and upgrading their skills comes from proving their detractors wrong and prevailing when arguments arise:

My personal drive for [mastering work-related knowledge] is to tell them or show that they are wrong about me. It’s like a ballplayer when you say “you can’t do this” or “you’re not prepared to succeed.” … I just say to myself I’m going to show everybody my own personal way that I can do this. But there are naysayers everywhere. … You can’t miss them. And it is so great to show them how wrong they are.

– 40-something skilled worker, Atlanta region

What motivates me? To prove a point. So that’s probably on the more negative side [laughs] to show that I can do it and kinda, “[Road rage gesture] to you. I did it.” That’s pretty raw, but to prove a point I will stubbornly study and study and study and figure out how to do it.

What motivates me? To prove a point. So that’s probably on the more negative side [laughs] to show that I can do it and kinda, “[Road rage gesture] to you. I did it.” That’s pretty raw, but to prove a point I will stubbornly study and study and study and figure out how to do it.

– 60-something working-class participant, St. Louis region

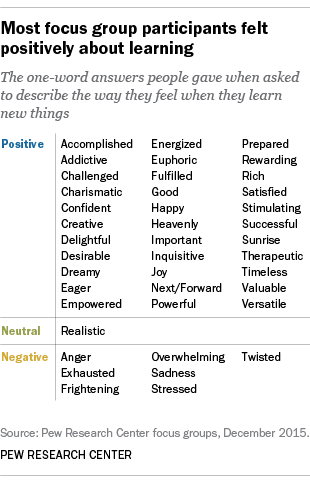

Learning brings its own rewards. There is undeniable stress for many as they adjust to the new economy. Yet, when asked to provide a single word to describe their feeling about learning, most of the focus group participants chose a positive rather than negative word. And they much more often spoke of the pleasure of learning than the pain of it. Their responses are listed in the adjacent table.