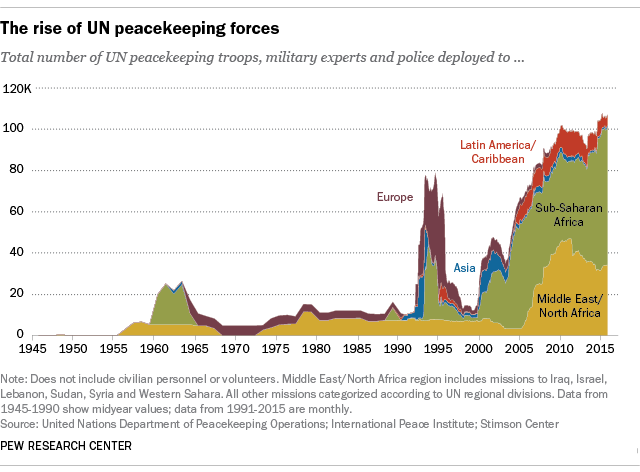

The number of United Nations peacekeeping forces around the world has peaked in recent months, after falling off in the late 1990s. Today, more than 100,000 uniformed peacekeepers are deployed under 16 different missions – with the highest numbers in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Sudan and South Sudan.

The first historical mission with a sizable military force was the UN Operation in the Congo (ONUC) in the early 1960s, which sought to restore order in the former Belgian colony that had fallen into violence. About 20,000 peacekeepers took part in the mission, during which then Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld died in a plane crash while flying into the region for diplomatic talks.

Peacekeeping activities were relatively infrequent for the next 25 years, but they spiked under the leadership of Secretary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali, who died in mid-February. During Boutros-Ghali’s January 1992 to December 1996 tenure, the number of ongoing missions rose from 10 to 18 – including high-profile operations in the former Yugoslavia, Somalia and Rwanda – while the number of peacekeeping forces reached a then high of nearly 79,000 in 1994, according to data from the UN, the Stimson Center and the International Peace Institute.

But those first years after the Cold War were seen as a period of trial and error for UN peacekeeping in general, and by 1999 the number of peacekeepers in the field dropped to about 12,000.

Amid that lull, Secretary-General Kofi Annan, who was head of peacekeeping under Boutros-Ghali, ordered internal reviews of the UN peacekeeping framework, examining their failures to prevent genocide in Rwanda and Srebrenica. These reviews led to the publication of the landmark “Brahimi Report” in 2000 (named for panel Chairman Lakhdar Brahimi), which recommended, among other reforms, that the UN be able to rapidly deploy its forces into conflict zones after authorization and be more aggressive in asserting itself.

The size of UN peacekeeping forces again increased in the 2000s, as their services were sought by a growing number of conflict-ridden countries and their neighbors. In October 2005, as the number of peacekeepers approached 70,000, Jean-Marie Guéhenno, then the head of peacekeeping operations, warned that his forces were being overextended, leading to a brief “phase of consolidation” in 2010.

Since the start of 2010, however, six new missions have been authorized (including four that today have more than 10,000 peacekeepers), while five have been phased out (of which two had more than 10,000 troops at their peak). By April 2015, the number of uniformed peacekeeping personnel – which includes troops, police and military advisers – reached a new high of about 108,000.

Today, UN peacekeeping’s legacy contains a mix of perceived successes (such as in Namibia and Mozambique), failures, and scandals (such as multiple allegations of sexual abuse, most recently in the Central African Republic). Many of the past challenges also remain: In a 2015 internal assessment by the High-Level Independent Panel on Peace Operations, known as the HIPPO report, officials warned: “A number of peace operations today are deployed in an environment where there is little or no peace to keep. … There is a clear sense of a widening gap between what is being asked of United Nations peace operations today and what they are able to deliver.”

It’s worth noting that peacekeeping missions and mandates must be unanimously approved by all permanent members of the Security Council, including the U.S. and Russia, a constraint that has prevented UN intervention in some conflict zones.

As of January 2016, the top contributors to peacekeeping forces are Ethiopia (8,326), Bangladesh (8,274), India (7,799) and Pakistan (7,625) – making up 30% of the total – followed by other developing and emerging nations, mostly in Africa and Asia. By contrast, European nations supply just 6% of total personnel contributions. (Brahimi criticized this dynamic as one in which the “rich contribute money and the poor contribute blood.”)

As of January 2016, the top contributors to peacekeeping forces are Ethiopia (8,326), Bangladesh (8,274), India (7,799) and Pakistan (7,625) – making up 30% of the total – followed by other developing and emerging nations, mostly in Africa and Asia. By contrast, European nations supply just 6% of total personnel contributions. (Brahimi criticized this dynamic as one in which the “rich contribute money and the poor contribute blood.”)

But this wasn’t always the case: In the mid-1990s, when the Balkan states of Europe were riddled with violence and UN peacekeepers were active in the area, European nations – particularly the UK and France – made up the largest shares of total contributions.

In September 2015, President Barack Obama presided over a UN peacekeeping summit, acknowledging that the “supply of well-trained, well-equipped peacekeepers can’t keep up with the growing demand” and promising renewed support for peace operations, mostly in the form of military experts, training and resources.

The United States’ contributions of UN forces peaked at 4,200 in October 1993, the month of the “Black Hawk Down” firefight in Somalia that left 18 Americans dead. (It was part of a separate U.S.-led mission but was related to UN goals.) At the time, the U.S. was the fourth-largest contributor of peacekeepers, making up 5.6% of the total UN force. But political and public pressure following the Somalia fiasco led the U.S. to withdraw its forces from the region in general, and the U.S.’s overall contributions have steadily dwindled since. Today, a record low share of UN peacekeepers are from the U.S. (just 76 personnel, or 0.07%).

However, the U.S. finances UN peacekeeping more than any other country (it’s charged with 28% of the total budget) – in accordance to a formula that apportions expenses based on the relative wealth of each country, among other factors. Japan (10.8%), France (7.2%), Germany (7.1%) and the UK (6.7%) are the other top contributors of funds.

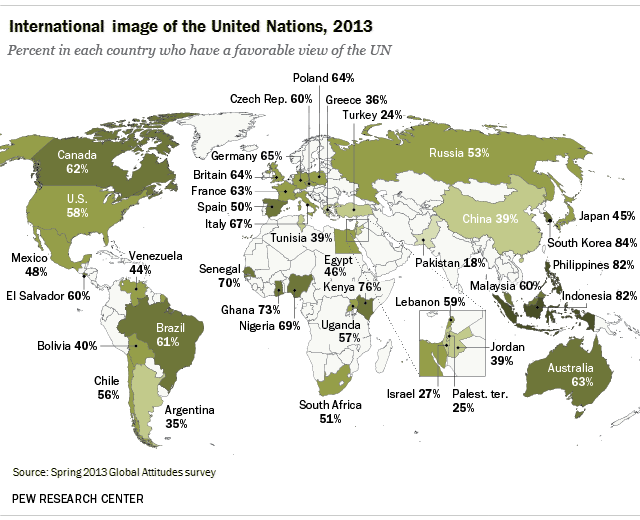

As recently as 2013, the UN maintained a strong international image: A global median of 58% across 39 countries saw the UN favorably, compared with a median of 27% who viewed it unfavorably, according to a Pew Research Center survey. UN support was highest in the Asia-Pacific and lowest in the Middle East. It was also generally liked in Europe, Africa and Latin America.