The death of Justice Antonin Scalia, and the subsequent partisan wrangling over whether the Senate should act on any nominee sent to it by President Obama, has cast a spotlight on an institution that many people know little about.

The death of Justice Antonin Scalia, and the subsequent partisan wrangling over whether the Senate should act on any nominee sent to it by President Obama, has cast a spotlight on an institution that many people know little about.

As a Fact Tank post last year noted, the court “remains an institution whose members – and even the facts about some of its most important decisions – are a mystery to many Americans.” In a 2013 survey, 20% incorrectly identified staunch conservative Scalia, rather than Anthony Kennedy, as the court’s most frequent “swing vote.” And a Gallup poll last summer found that Scalia was unknown to 32% of Americans, while 12% had heard of Scalia but didn’t have an opinion about him.

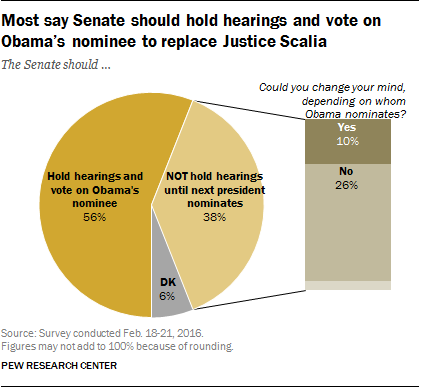

But in a Pew Research Center survey released earlier this week, about seven-in-ten Americans said they had heard a lot (45%) or a little (26%) about Scalia’s death and the vacancy on the court; fully 94% expressed an opinion on whether the Senate should hold hearings and vote on Obama’s eventual nominee.

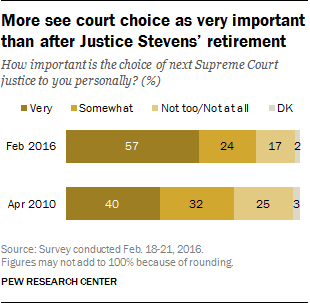

Not only that, but 57% said the choice of a new Supreme Court justice was “very important” to them personally, and 24% said it was “somewhat important.” In April 2010, after Justice John Paul Stevens announced his retirement from the court, and before Obama named Elena Kagan as his replacement, just 40% viewed the choice of a new Supreme Court justice as very important.

Not only that, but 57% said the choice of a new Supreme Court justice was “very important” to them personally, and 24% said it was “somewhat important.” In April 2010, after Justice John Paul Stevens announced his retirement from the court, and before Obama named Elena Kagan as his replacement, just 40% viewed the choice of a new Supreme Court justice as very important.

Such high levels of interest and engagement weren’t common in past Supreme Court nomination battles. Consider Robert Bork, the last Supreme Court nominee to be rejected by the Senate. In July 1987, President Ronald Reagan named Bork to succeed the retiring Lewis Powell, but the nomination ran into immediate and forceful criticism from the liberal side of the political spectrum. After a fierce four-month battle capped by a three-day debate on the Senate floor, Bork’s nomination failed on a 42-58, largely party-line vote. (Anthony Kennedy ultimately was confirmed to replace Powell.)

Despite the intense level of news coverage over the Bork nomination, a September 1987 survey by the Times Mirror Center (which later became Pew Research Center) found that nearly half of the public either had never heard of Bork (21%) or had no opinion about him (28%). A quarter of the public (26%) didn’t express an opinion about whether Bork should or shouldn’t be confirmed.

Nearly five decades ago, a series of Supreme Court nomination battles was detonated by President Lyndon Johnson’s nomination of Associate Justice Abe Fortas to succeed Earl Warren as chief justice. Fortas’ 1968 nomination quickly turned controversial for a mix of reasons, including Fortas’ continuing close relationship with LBJ, questions about his personal finances, and conservative distaste for the liberal rulings of the Warren Court of which he was a part. Ultimately, Fortas’ nomination foundered on a Senate filibuster.

Although the nomination fight was very much in the news that summer and fall, a July 1968 Harris survey found that 30% of Americans were “not sure” whether Fortas should or shouldn’t be confirmed; 44% said they had no opinion on whether or not he was an able justice.

Fortas’ ethical troubles deepened, and he resigned from the court in May 1969. The new president, Richard Nixon, nominated federal judge Clement Haynsworth to replace Fortas, but Haynsworth too ran into criticism, particularly from civil-rights groups and organized labor. The Senate rejected Haynsworth in November 1969; the following spring it also turned down Nixon’s second choice for the seat, G. Harrold Carswell.

A Harris survey conducted in February 1970, while Carswell’s nomination was pending, found that 38% of Americans had no opinion on Haynsworth’s rejection. A similar Harris survey in January 1971, after Harry Blackmun had finally been confirmed to the seat, found a similar percentage (39%) with no opinion on the Senate’s rejection of Haynsworth and Carswell.

By contrast, the 1991 confirmation battle surrounding Clarence Thomas did appear to engage the public as it went on. Thomas’ nomination, contentious from the start, became even more so after a former colleague, Anita Hill, accused him of sexually harassing her. A Times Mirror Center survey taken in July 1991, shortly after Thomas was nominated, found 35% of the public undecided about whether or not he should be confirmed. But by October, in an ABC News/Washington Post poll taken just after the Senate narrowly confirmed Thomas, only 4% of the public had no opinion on whether or not the Senate had done the right thing.