Under pressure from Congress to improve tracking of foreign visitors, the Department of Homeland Security has produced its first partial estimate of those who overstay their permits to be in the U.S. Out of 45 million U.S. arrivals by air and sea whose tourist or business visas expired in fiscal 2015, the agency estimates that about 416,500 people were still in the country this year.

Under pressure from Congress to improve tracking of foreign visitors, the Department of Homeland Security has produced its first partial estimate of those who overstay their permits to be in the U.S. Out of 45 million U.S. arrivals by air and sea whose tourist or business visas expired in fiscal 2015, the agency estimates that about 416,500 people were still in the country this year.

The government’s report was limited in scope and includes no reliable trend data that could shed light on whether overstays are growing or declining.

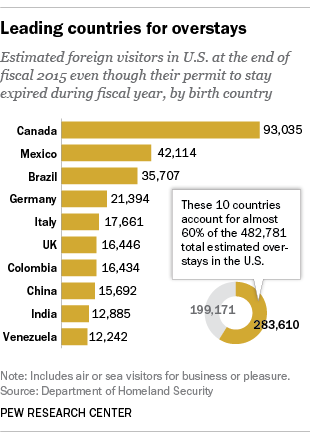

The nation with the most visitors who failed to leave at the end of their authorized stay was Canada, followed by Mexico and Brazil, according to the report. Among total foreign arrivals counted in the report, those three nations accounted for more than a third of those who overstayed.

The nation with the most visitors who failed to leave at the end of their authorized stay was Canada, followed by Mexico and Brazil, according to the report. Among total foreign arrivals counted in the report, those three nations accounted for more than a third of those who overstayed.

Congress has required the government to improve tracking of foreign visitors who overstayed their deadline to leave since the late 1990s, but interest ramped up after five of the Sept. 11, 2001, plane hijackers turned out to be foreigners on expired visas. Data on those who overstay also could add detail to the portrait of the nation’s 11.3 million unauthorized immigrants, because it is not known how many arrived legally versus illegally.

The country profile of foreign visitors who overstay and became unauthorized is somewhat different from that of unauthorized immigrants overall. Mexicans made up 49% of unauthorized immigrants in 2014 (including some who arrived decades ago), but according to the report, they account for only about 9% of foreigners (or 42,000 people) who arrived by air and sea, overstayed and had not left by the end of fiscal 2015. Canadians, meanwhile, account for about 1% of unauthorized immigrants in Pew Research Center’s latest estimate for 2012, but 19% of overstayers who had not departed by the end of fiscal 2015, or 93,000 people.

The Homeland Security report on overstays was limited to foreigners whose permission to be in the U.S. expired during the 2015 fiscal year, which ended Sept. 30. It examined admissions for business or pleasure by air or sea, which were 85% of arrivals with visitor permits that expired in fiscal 2015, but not other smaller categories such as visas for students or for temporary workers and their families. It covered only those who arrived by sea or air, not land arrivals from Canada or Mexico, which account for most temporary visitors.

The report indicates that the number of foreign visitors who overstay dwindles over time. In all, the report said that out of the 45 million arrivals who were supposed to depart in fiscal 2015, about 527,000 remained in the country after their permission to stay expired, a rate of 1.17%. Some of these overstays later departed, but 483,000 were still in the U.S. at the end of the fiscal year on Sept. 30, a rate of 1.07%. More left the U.S. after that, so by Jan. 4, 2016, an estimated 416,500 were still in the country, a rate of 0.9%. The DHS report said some have likely left since then, or obtained or renewed a legal visa.

Homeland Security officials say they intend to improve their data collection, specifically to include student visa categories, and to issue regular updates in order to supply trend data.

The government gets data on foreigners who leave the U.S. from airlines and passenger vessels, which since 2005 have been required to collect it. DHS is expanding collection of biometric data, mainly fingerprints, to track foreign travelers’ comings and goings by air and sea, but widespread implementation for outgoing flights is stalled. At land borders, the U.S. and Canada exchange data on foreign travelers in each direction, but the U.S. gets little information about foreign visitors who leave for Mexico. DHS reports more than 110 million entries that do not require entry visas over the land borders; the vast majority of these are commuters or others coming for short visits.

The report also included overstay rates overall and by country.

The overstay report broke down the statistics into three groups of countries: countries with visa-waiver programs, where the U.S. does not require a visa for temporary visits; countries for which entry visas are required; and Canada and Mexico. Canada and Mexico both had above-average overstay rates, as did countries that do not have visa-waiver agreements with the U.S. As a group, countries with visa-waiver agreements (mostly in Europe) had a below-average overstay rate, though some individual countries, including Chile, Hungary and Portugal, had above-average rates.

Homeland Security’s methodology and reported results have at least two potential drawbacks. First, the number of overstays counts each person who overstays once, but the 45 million admissions covered by the report include some people who came to the U.S. more than once with visas or other permits that expired in fiscal 2015. If each visitor were counted only once, the 45 million admissions figure would be smaller, and the share of people who overstay would be larger than the reported overstay rate. DHS did not report the number of temporary visitors for business or pleasure who enter the U.S. more than once during the year.

But a second problem, which could be inflating the overstay rate, is that various record-keeping challenges make it difficult to match arrival and departure records for the same person. If the government does not match these records because of data errors, a person who actually left the country would be erroneously counted as an overstayer. Similarly, if not all departure records are collected by the airlines and transmitted to DHS, erroneous reports of overstays would result.