Teens and young adults were among the groups hit hardest by the global financial crisis. And while many young people have since regained their footing – as employees, students or both – there are still millions in the U.S. and abroad who are neither working nor in school. Though sometimes referred to as “disconnected” or “detached” youth, globally those young people often are called “NEETs” – because they are neither employed nor in education or training.

Although NEET rates rose both in the U.S. and the EU during and after the crisis, they jumped higher but have fallen faster in the U.S. By contrast, many EU countries’ NEET rates remain well above pre-crisis levels. (While similar, the U.S. and EU measures aren’t directly comparable – in part because the EU begins tracking young people’s labor-force participation at 15 rather than 16, and also because apprenticeships and other workplace-based training is more common in Europe than in the U.S.)

Labor economists are paying increasing attention to NEETs – especially when, as in much of Europe, NEET rates are persistently high. They fear that without assistance, economically inactive young people won’t gain critical job skills and will never fully integrate into the wider economy or achieve their full earning potential. Some observers also worry that large numbers of NEETs represent a potential source of social unrest.

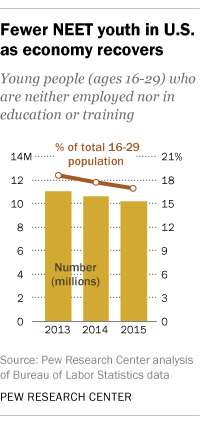

In 2015, there were nearly 10.2 million NEETS ages 16 to 29 in the U.S., or 16.9% of that age bracket’s total population, according to a new Pew Research Center analysis of data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. That represents a modest decline over recent years: In 2013, there were just over 11 million NEETs in the U.S., representing 18.5% of the 16-to-29 population, according to our analysis.

In 2015, there were nearly 10.2 million NEETS ages 16 to 29 in the U.S., or 16.9% of that age bracket’s total population, according to a new Pew Research Center analysis of data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. That represents a modest decline over recent years: In 2013, there were just over 11 million NEETs in the U.S., representing 18.5% of the 16-to-29 population, according to our analysis.

Precisely corresponding data aren’t available for prior years, because the monthly Current Population Survey used by BLS only began collecting detailed school-enrollment data from Americans ages 25 and older in 2013.

However, longer-trend CPS data are available for 16- to 24-year-olds. Those numbers show that the NEET rate among that group generally follows the economic cycle. It fell between 1985 and 2000, from 19.5% to 14.3%, except for a bump during the early-1990s recession. The 16-to-24 NEET rate rose again following the early-2000s recession, fell back to 14.5% in 2007, then jumped during the Great Recession. The rate has ratcheted lower since peaking at 17.6% in 2010; last year it was 15.7%, a hair above what it was in 2008.

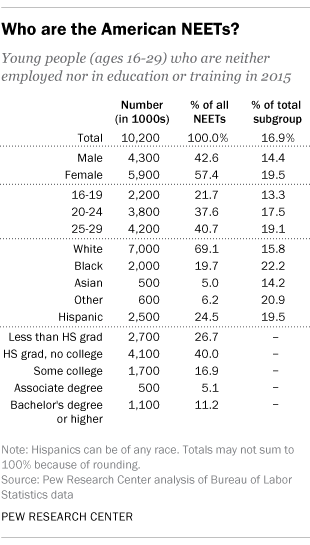

What does the nation’s NEET population look like? According to our analysis of the 2015 data on 16-to-29-year-olds, they’re more female than male (57% to 43%), and two-thirds have a high school education or less. Blacks and Hispanics are most likely to be NEETS: 22% of young black people ages 16-29 are neither employed nor in school, versus 16% of young whites. About 20% of young Hispanics are NEET.

What does the nation’s NEET population look like? According to our analysis of the 2015 data on 16-to-29-year-olds, they’re more female than male (57% to 43%), and two-thirds have a high school education or less. Blacks and Hispanics are most likely to be NEETS: 22% of young black people ages 16-29 are neither employed nor in school, versus 16% of young whites. About 20% of young Hispanics are NEET.

A separate analysis by Measure of America (a project of the Social Science Research Council), while not directly comparable, adds additional context. That report, using 2013 data from the American Community Survey, found considerable variation in the estimated share of what it calls “disconnected youth” (ages 16 to 24 only) in nearly 100 of the most populous metropolitan areas. The metro areas with the highest rates were Memphis (21.6%); Bakersfield, California (21.2%); and Lakeland-Winter Haven, Florida (20.4%). The lowest rates were in Omaha-Council Bluffs, Nebraska-Iowa, and Fairfield County, Connecticut (both 7.7%), and in Boston (8.2%). In general, higher disconnection rates were more commonly found in the South and West than in the Northeast and Midwest.

Noting that “disconnected youth come overwhelmingly from communities that have long been isolated from the mainstream,” the researchers identified six factors associated with high rates of youth disconnection: high rates of disconnection a decade earlier, low levels of human development (as measured by an index combining health, education and income indicators), high rates of poverty and adult unemployment, low levels of adult educational attainment, and a high degree of racial segregation.

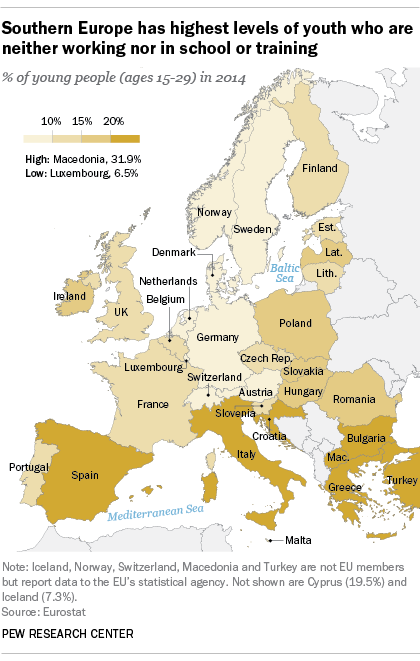

The European Union also saw a surge in its NEET population during and after the financial crisis. (The EU’s statistical agency, Eurostat, sets the lower age bound of NEETs at 15 instead of 16.) In 2014, the most recent year for which data are available, 15.4% of the 15-to-29 population – or roughly 13.4 million young people across the EU – were neither employed nor in school or other training, a rate that has changed little since 2010. As in the U.S., more NEETs were young women (55% of the total) than young men (45%).

The NEET rate varies considerably among the EU’s 28 member nations: Those with the highest rates were in struggling southern Europe, led by Greece and Italy; more than a quarter of 15- to 29-year-olds in those countries were NEETs (26.7% and 26.2%, respectively). Luxembourg (6.5%) and Denmark (7.3%) had the lowest NEET rates in the EU.

The NEET rate varies considerably among the EU’s 28 member nations: Those with the highest rates were in struggling southern Europe, led by Greece and Italy; more than a quarter of 15- to 29-year-olds in those countries were NEETs (26.7% and 26.2%, respectively). Luxembourg (6.5%) and Denmark (7.3%) had the lowest NEET rates in the EU.

The NEET rate trends in the largest EU economies vary considerably, both with each other and with the pattern observed in the U.S. In Germany, for example, the NEET rate peaked in 2005 and has gradually declined ever since; in Italy, by contrast, its already high rate began rising higher in 2008 and, as of 2014, had yet to stop. The U.K.’s NEET rate fell sharply in the mid-2000s, jumped in 2007 and peaked in 2011, falling somewhat since. And France’s rate has been remarkably stable, varying only between 12.8% and 15.1% over the entire 2000-2014 period examined.