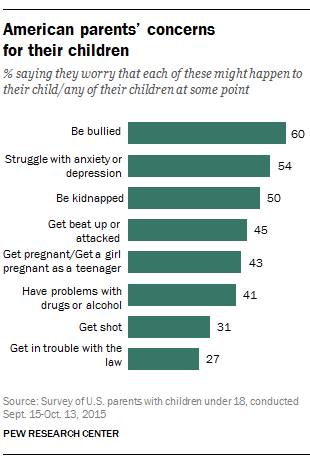

Worrying about your kids is one of the defining traits of being a parent. But the nature of that worrying varies considerably across demographic groups, according to a recent Pew Research Center report.

Worrying about your kids is one of the defining traits of being a parent. But the nature of that worrying varies considerably across demographic groups, according to a recent Pew Research Center report.

Low-income parents, for instance, are more concerned about teen pregnancy and their kids getting in trouble with the law than are higher-income parents. Black parents are more likely than white parents to worry about their children being shot, while white parents are more likely than black parents to worry that their children will struggle with anxiety or depression. Hispanic parents worry more than black or white parents about all eight measures we asked about, from being bullied to having problems with drugs or alcohol (a trend driven primarily by foreign-born Hispanics, who tend to have lower incomes and less education).

To examine the actual incidence of the areas of concern discussed in the Center’s report, we analyzed national statistics from a variety of sources on getting shot, getting in trouble with the law, teen pregnancy, kidnappings, drug and alcohol use, anxiety/depression, getting beat up and being bullied. Here’s what we found:

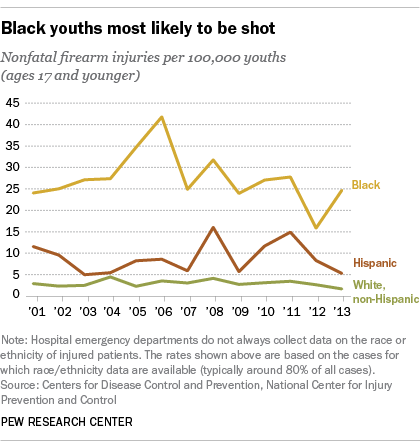

Getting shot: Relatively few minors (ages 17 and younger) are shot in any given year, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s database of fatal and nonfatal injury reports. However, black youths are far more likely than white or Hispanic youths to be injured by gunfire or fatally shot.

Getting shot: Relatively few minors (ages 17 and younger) are shot in any given year, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s database of fatal and nonfatal injury reports. However, black youths are far more likely than white or Hispanic youths to be injured by gunfire or fatally shot.

In 2013, the last year for which there are complete data, 1,258 youths were reported killed by firearms (equivalent to 1.71 per 100,000), and 6,104 suffered nonfatal firearm injuries (8.29 per 100,000). In 2014, total youth deaths by firearm rose to 1,331, or 1.81 per 100,000; injury data for 2014 aren’t yet available. (All these figures exclude injuries from BB guns and pellet guns.)

In 2014, the rate of firearm deaths for black youths was 4.26 per 100,000, almost three times the rate for white youths and nearly four times the rate for Hispanic youths. Hospital emergency departments, from which the CDC gathers its injury data, don’t always obtain information on race and ethnicity for their patients. But based on the 80% or so of nonfatal firearm injury cases involving juveniles in 2013 for which race and ethnicity data are available, the disparity among different subpopulations was stark: 1.68 per 100,000 for white youths, 5.3 per 100,000 for Hispanic youths and 24.67 per 100,000 for black youths.

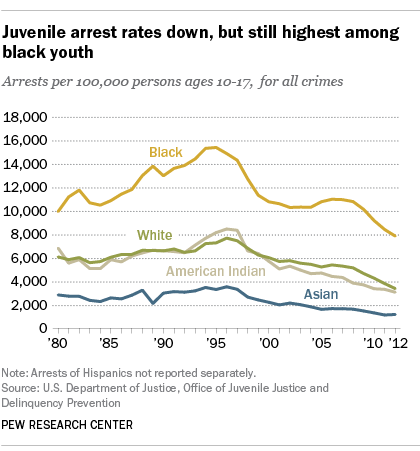

Trouble with the law: Overall juvenile arrest rates have fallen by more than half after peaking in the mid-1990s, according to the federal Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. In 2012, nearly four of every 100 youths (ages 10 to 17) were arrested, down from about 8.5 per 100 in 1996.

Trouble with the law: Overall juvenile arrest rates have fallen by more than half after peaking in the mid-1990s, according to the federal Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. In 2012, nearly four of every 100 youths (ages 10 to 17) were arrested, down from about 8.5 per 100 in 1996.

However, while all racial subgroups contributed to the decline (the OJJDP doesn’t report separately on Hispanics), the arrest rate for black youths is still more than twice that of any other group.

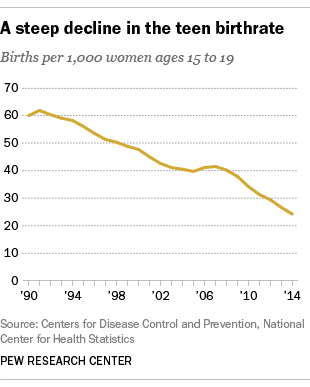

Teen pregnancy: The birthrate for 15- to 19-year-olds (the metric tracked by federal researchers) has been dropping for decades and hit a record low in 2014. There were just 24.2 births per 1,000 teen females that year, compared with 61.8 per 1,000 in 1991 and 41.5 as recently as 2007.

Teen pregnancy: The birthrate for 15- to 19-year-olds (the metric tracked by federal researchers) has been dropping for decades and hit a record low in 2014. There were just 24.2 births per 1,000 teen females that year, compared with 61.8 per 1,000 in 1991 and 41.5 as recently as 2007.

Over the past few decades, birthrates have not only fallen among teens of all races and ethnicities reported, but have fallen the most for those with the highest rates. In 1991, for instance, non-Hispanic black teens had the highest birthrate (118.2 per 1,000) of any racial or ethnic group – 90.9 points higher than Asian teens, who had the lowest rate (27.3 per 1,000). By 2013, the spread between the highest subgroup birth rate (Hispanic teens, 41.7 per 1,000) and the lowest (Asian teens, 8.7 per 1,000) was just 33 points, according to the CDC data.

Every state in the nation, as well as the District of Columbia, has a lower teen birthrate than it did in the early 1990s. The District’s decline (from 112.8 per 1,000 in 1993 to 28.4 per 1,000 last year) was the steepest. But birthrates still vary considerably across the country: Arkansas had the highest (39.5 per 1,000 last year), while Massachusetts had the lowest (10.6 per 1,000).

Kidnapping: Reliable data on child abductions are notoriously hard to come by, but what information there is suggests that abductions by strangers aren’t common.

The most pertinent data appear to come from the FBI via its National Crime Information Center, which law enforcement agencies around the country use to share information. Of the 635,000-plus missing-person cases reported to the NCIC last year, nearly 467,000 involved juveniles below the age of 18. But according to an optional data field, completed in about half of all missing-person cases, only 332 stranger abductions were reported last year; since 2007, the number of stranger abductions has ranged between 200 and 520.

Among juveniles, abductions by non-custodial parents are much more common than stranger abductions. The database lists 2,249 children as having been abducted by non-custodial parents; since 2007, the number has ranged between 2,000 and 3,000 a year. The great majority of juvenile disappearances – at least 302,000 – were characterized as runaways; in only 4,800 cases did circumstances suggest that the disappearance may have been involuntary.

Anxiety and depression: Available data suggest that a quarter of teens have experienced some sort of anxiety disorder (such as phobias, panic disorder or post-traumatic stress disorder) at some point in their lives, according to the National Institute of Mental Health. For 5.9% of teens, their disorder causes or did cause “severe impairment.” Anxiety disorders are more common among teen girls than boys (30.1% versus 20.3%).

Anxiety and depression: Available data suggest that a quarter of teens have experienced some sort of anxiety disorder (such as phobias, panic disorder or post-traumatic stress disorder) at some point in their lives, according to the National Institute of Mental Health. For 5.9% of teens, their disorder causes or did cause “severe impairment.” Anxiety disorders are more common among teen girls than boys (30.1% versus 20.3%).

About one-in-ten adolescents, or around 2.6 million, have experienced major depression in the past year, according to 2013 data reported by NIMH; for 7.7%, their depression caused severe impairment. Depression was three times as common among teen girls as teen boys (16.2% versus 5.3%). Among racial and ethnic groups, mixed-race teens were the most likely to report a major depressive episode in the previous year (13%); native American teens were least likely to report depression (4.5%).

Bullying: This, unfortunately, is another case in which solid data can be hard to come by. The 2013 Youth Risk Behavior Study (which covered only high-school students) found that 19.6% had been bullied on school property in the previous 12 months, and 14.8% had been electronically bullied. In both cases, white teens and female teens were more likely to say they’d been bullied.

Drugs and alcohol: Overall drug use among young people has been more or less unchanged in recent years after rising sharply in the 1990s, according to the University of Michigan’s long-running “Monitoring the Future” survey. Around 15% of eighth-graders, three-in-ten high-school sophomores and four-in-ten seniors report some use of illicit drugs (either illegal or prescription drugs not under a doctor’s orders) in the past 12 months. Marijuana is by far the most commonly used drug, at all grade levels; 10th- and 12th-graders are next-most likely to report using amphetamines and the prescription drug Adderall, while inhalants are the second-most frequently used drugs among eighth-graders.

Drugs and alcohol: Overall drug use among young people has been more or less unchanged in recent years after rising sharply in the 1990s, according to the University of Michigan’s long-running “Monitoring the Future” survey. Around 15% of eighth-graders, three-in-ten high-school sophomores and four-in-ten seniors report some use of illicit drugs (either illegal or prescription drugs not under a doctor’s orders) in the past 12 months. Marijuana is by far the most commonly used drug, at all grade levels; 10th- and 12th-graders are next-most likely to report using amphetamines and the prescription drug Adderall, while inhalants are the second-most frequently used drugs among eighth-graders.

At the same time, alcohol and cigarette use has been declining for many years: Last year, 35.3% of seniors reported any alcohol use in the past 30 days (down from 54% in 1991), and only 11.4% reported smoking cigarettes (down from 36.5% in the peak year of 1997). Indeed, 12th-graders were about as likely to have smoked marijuana in the past 30 days (21.3%) as to have gotten drunk (20.6%).

Getting beat up: The 2013 youth risk study found that about a quarter (24.7) of high-school students said they’d been in a physical fight at least once in the past 12 months (down from 42.5% in 1991), though only 3.1% needed medical attention.

Black students were most likely to say they’d been in a fight – nearly 35%, compared with 28.4% of Hispanic high-schoolers and 20.9% of white students. Just over 8% said they’d been in a fight on school property, and 7.1% said they’d skipped school at least once in the past 30 days because of safety concerns.