Pope Francis later this week makes his first apostolic trip to sub-Saharan Africa – a part of the world where the number of Muslims and Christians is projected to increase dramatically over the next 35 years. It also is a region where the tension and distrust between these two religious groups has been rising.

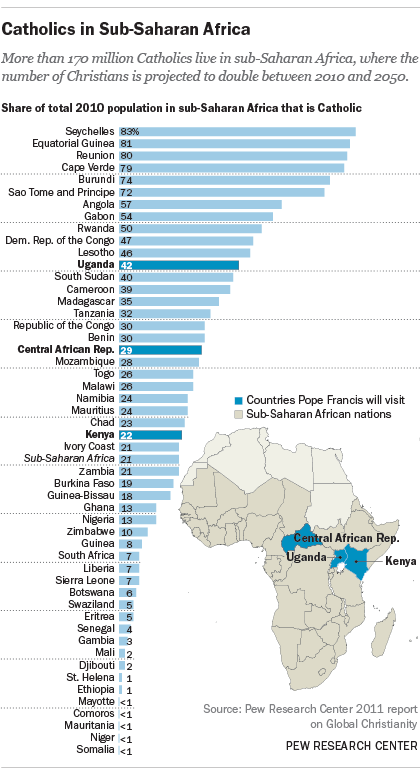

Not surprisingly, the three countries on the pope’s itinerary all have sizable Catholic populations. Catholics in Uganda numbered 14 million as of 2010, making up 42% of the population, while Catholics made up 22% of the population in Kenya (9 million) and 29% in the Central African Republic (1.3 million), according to a Pew Research Center report on Global Christianity. All in all, more than 170 million or about one-in-five (21%) of sub-Saharan Africa’s inhabitants were Catholic in 2010.

Not surprisingly, the three countries on the pope’s itinerary all have sizable Catholic populations. Catholics in Uganda numbered 14 million as of 2010, making up 42% of the population, while Catholics made up 22% of the population in Kenya (9 million) and 29% in the Central African Republic (1.3 million), according to a Pew Research Center report on Global Christianity. All in all, more than 170 million or about one-in-five (21%) of sub-Saharan Africa’s inhabitants were Catholic in 2010.

A majority of all people in the region (63%) are Christians. More than half of the Christians in sub-Saharan Africa are Protestants (including Pentecostals and evangelicals), while about a third are Catholics and a smaller share are Orthodox Christians. Among non-Christians in the region, most (about 30% of the total population) are Muslims.

Due to rapid population growth, both Islam and Christianity are expected to have more than twice as many adherents in the region by 2050 as they did in 2010, according to our April report this year. Christians will increase from 517 million to more than 1.1 billion, and Muslims will go from 248 million to 670 million.

As a result, the importance of sub-Saharan Africa in the global religious community will be elevated as it becomes home to larger global shares of both faiths by midcentury. By 2050, the region will account for 38% of the world’s Christians and 24% of the world’s Muslims (as opposed to 24% and 16%, respectively, in 2010).

But this growth among sub-Saharan Africa’s religious communities has, in recent years, been accompanied by violent clashes, including in all of the countries the pope is visiting. In the Central African Republic, for instance, a mostly Muslim rebel coalition overthrew the country’s Christian president in 2013, sparking violent attacks on civilians by both Muslim and Christian militias. And in Kenya, members of Somalia’s extremist Islamist group al-Shabab attacked a Nairobi shopping mall in 2013, gunning down at least 60, and a university in Garissa in 2015, leaving nearly 150 people dead, most of them Christians.

As in all of his travels, Francis will be promoting interreligious dialogue and understanding. But on this trip, he will encounter wariness among sub-Saharan Africa’s major religious communities. Pew Research Center’s 2010 study of Islam and Christianity in sub-Saharan Africa found that in eight of the 19 nations surveyed, at least three-in-ten people said that religious conflict was a “very big” problem in their country. The study also found mutual perceptions of hostility: A median of 28% of Christians said that many or most Muslims are hostile to Christians, and a median of 23% Muslims said that many or most Christians are hostile to Muslims.

In addition, many Africans have incompatible religious aspirations. For instance, substantial majorities of both faith groups said they would like to see their civil law systems based on religion. A median of 60% of Christians in the 19-nation survey reported they would like civil law based on the Bible, and a median of 63% of Muslims said they would like Islamic law, or sharia, to become the law of the land.