The Chinese government recently announced it would further relax its decades-old one-child policy, but this shift might not dramatically affect the birth rate and the gender imbalance in China – at least not in the near term.

The Chinese government recently announced it would further relax its decades-old one-child policy, but this shift might not dramatically affect the birth rate and the gender imbalance in China – at least not in the near term.

Why? Policy isn’t the only factor influencing a country’s demographic changes. China’s rapid economic development, its urbanization and its culture will continue to play a role in family size and the population’s gender makeup.

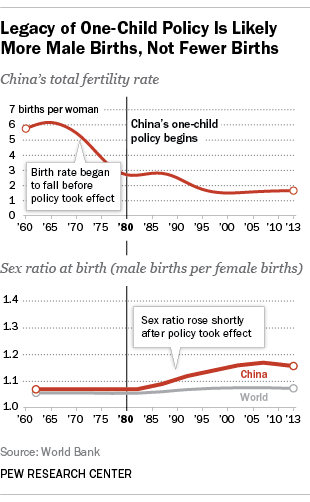

China’s fertility rate certainly declined since the advent of the one-child policy in 1980. But that decline seems to be a continuation of a trend that was already well underway prior to the policy’s official implementation. The country’s total fertility rate stood at almost six births per woman in the 1960s, but by 1980, it had already fallen below three births per woman. As of 2013, the typical Chinese woman was expected to have about 1.6 children in her lifetime.

Fertility rates typically fall as countries become more urbanized and more economically developed, and these factors likely explain much of the decline in the Chinese birthrate. Indeed, across Asia, even countries without a one-child policy have experienced a rapid decline in fertility rates in recent decades.

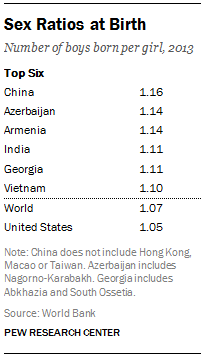

China’s one-child policy likely contributed to one of the most skewed sex ratios in the world. Today, there are about 116 boys born for every 100 girls born – a ratio much higher than the global one, 107 boys for every 100 girls.

China’s one-child policy likely contributed to one of the most skewed sex ratios in the world. Today, there are about 116 boys born for every 100 girls born – a ratio much higher than the global one, 107 boys for every 100 girls.

In the decades before the one-child policy was first implemented in 1980, China’s boy-girl birth ratio looked similar to the global average. However, the ratio rose markedly in the years that followed.

Even though the policy may have contributed to the changing gender balance, it’s not clear that ending the one-child policy will immediately lead to an increasing share of girl babies, given the strong cultural preference for boys.

With the constraints of urbanization and economic development, many Chinese families may continue to have only one child. If that’s the case, the son preference may lead to the persistence of sex ratios favoring boys in the short term, though some experts say that, in the long run, China’s unbalanced sex ratio may even out.

Note: This is an update of a post originally published on Nov. 15, 2013.