Last week’s Islamic State attacks in Paris have heightened concerns about possible security threats posed by the hundreds of thousands of Middle Eastern refugees pouring into Europe. And Europeans aren’t the only ones concerned: Opposition is building in the U.S. to the Obama administration’s plans to admit up to 10,000 refugees from Syria’s civil war.

A new Bloomberg Politics poll found that 53% of Americans don’t want to accept any Syrian refugees at all; 11% more would accept only Christian refugees from Syria. More than two dozen governors, most of them Republicans, have said they’ll oppose Syrian refugees being resettled in their states. And on Thursday the House of Representatives passed a bill blocking the admission of Syrian and Iraqi refugees unless they pass strict background checks.

The U.S. cap on refugee admissions was raised to 85,000 this fiscal year from 70,000 in fiscal 2015, largely to accommodate the planned increase in Syrian refugees and, more broadly, help deal with the influx of hundreds of thousands of migrants from that country, Iraq, Afghanistan and elsewhere into Europe. In a Pew Research Center survey taken in September, Americans narrowly approved of that policy shift (51% to 45%), though it’s unknown whether public opinion has shifted after the Paris attacks.

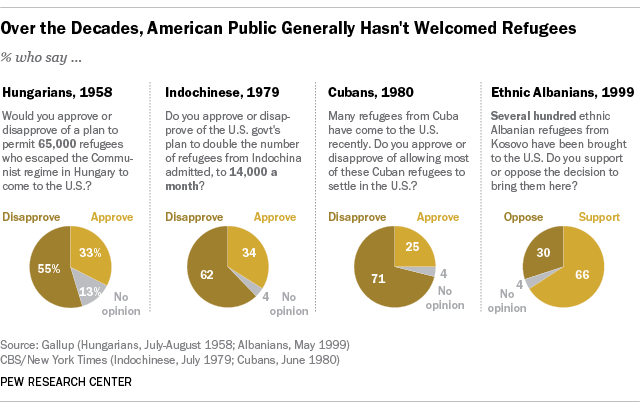

A look back into the opinion-polling archives (courtesy of Cornell’s Roper Center for Public Opinion Research) shows that American opposition to admitting large numbers of foreigners fleeing war and oppression has been pretty consistent, regardless of official government policy. We examined instances over the past eight decades where large groups of refugees from specific countries or regions were seeking admission, typically above and beyond the immigration rules in place at the time, and for which there was reliable polling data. Here’s what we found:

Before and after World War II

In the years leading up to the Second World War, as has been noted elsewhere, large majorities of Americans opposed allowing refugees from European dictatorships to come to the United States. In 1938, the polling firm Roper found that 67% opposed “German, Austrian and other political refugees” coming to the U.S., versus 18% who would allow them to come and 5% who would encourage them to come. In 1939, a Gallup poll found similar opposition when it asked more specifically about support for “10,000 refugee children from Germany” coming to the United States.

The war uprooted millions of Europeans from their homes; by the end of 1947 there were still an estimated 800,000 “displaced persons.” Some U.S. governors with declining populations in their states said there was room for refugees, but public attitudes remained less than welcoming: In a 1948 Gallup poll, for example, 57% said they would disapprove of any plans to resettle about 10,000 displaced Europeans in their state. Nonetheless, in 1948 Congress passed the Displaced Persons Act, which authorized the entry of 200,000 (later raised to 415,000) European refugees above normal immigration quotas. By the end of 1952, just over 400,000 people – mostly from Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union – had been admitted under the law.

Hungary, 1950s

After Soviet troops crushed the Hungarian uprising of 1956, nearly 200,000 Hungarians fled to Austria and Yugoslavia. In July 1958, Gallup asked what Americans thought about a suggestion that 65,000 Hungarian refugees be allowed to resettle in the U.S. Although Cold War tensions were running high, more than half (55%) disapproved of the idea, with only 33% approving of it. In the end, 30,752 Hungarians were admitted under the Hungarian Refugee Act of 1958.

Indochina, 1970s

Following the final collapse of South Vietnam in 1975, the U.S. evacuated some 130,000 Indochinese – Vietnamese, Cambodians and Laotians – fleeing the new Communist government. Americans were deeply divided on whether these refugees should be allowed to live in the United States: In a May 1975 Harris poll, for example, 37% were in favor, 49% opposed, and 14% weren’t sure. Nonetheless, the refugees were allowed to stay.

Later in the decade, hundreds of thousands of people living in Vietnam (including many ethnic Chinese) began leaving the country in overcrowded boats. At the same time, thousands of Cambodians and Laotians were escaping their countries over land. In response to the humanitarian crisis, President Jimmy Carter in June 1979 doubled the number of Indochinese refugees the U.S. had previously agreed to accept, to 14,000 a month. The move was not popular: In a CBS News/New York Times poll the following month, 62% disapproved of Carter’s action. But between 1980 and 1990, according to federal immigration data compiled by Pew Research Center, nearly 590,000 refugees from Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos were admitted into the U.S.

Cuba in 1980 and Haiti in 1994

The United States experienced its own “boat people” phenomenon in 1980, when the Cuban government allowed tens of thousands of people to leave the island in what became known as the Mariel boatlift. By the time the boatlift ended in late October that year, some 125,000 Cubans had arrived in south Florida. Under U.S. law governing Cuban emigrants, the refugees were allowed to stay once they reached U.S. soil.

The boatlift was not popular among Americans, particularly after media reports that criminals and mental patients were among the refugees (though ultimately only about 2,700, or 2.2%, were returned to Cuba). In a June 1980 CBS/New York Times poll, 71% said they disapproved allowing the Cubans to settle in the U.S.

A second wave of Cuban emigration to the U.S. occurred in 1994, accompanied by several thousand Haitians fleeing that country’s political turmoil and grinding poverty. Public opinion on these migrations was even more negative: In a September 1994 CBS/New York Times poll, large majorities disapproved of letting the refugees settle in the U.S. – 80% vs. 15% approval in the case of the Cubans, 77% vs. 19% in the case of the Haitians. The official U.S. response was very different from in 1980: More than 30,000 Cubans and 20,000 Haitians were intercepted at sea and interned at the U.S. base at Guantanamo Bay. Most of the Cubans eventually were admitted to the U.S., but only about half the Haitians were, according to a Brookings Institution report.

Kosovo, 1999

During the 1998-99 war between what was left of Yugoslavia and the Kosovo Liberation Army, roughly a million Kosovars – half the territory’s population – were either refugees in neighboring countries or internally displaced. In April 1999, as part of a multinational response to the crisis, the U.S. agreed to accept up to 20,000 Kosovar refugees. Public opinion on the move was split but more favorable toward taking the refugees than in previous crises: In a CBS/New York Times poll taken that month, 40% said accepting the refugees was the right thing for the U.S. to do, 31% said the U.S. should do less, and 19% said the U.S. should do more. In the end, according to State Department data, just over 14,000 Kosovars were admitted into the country.