In 2000, the United Nations put in place ambitious goals to lift people out of extreme poverty, and sub-Saharan Africa was one of the regions with the most room for improvement. The region had one of the highest percentages of people living in extreme poverty, the highest number of deaths among children under 5 and among mothers, and the lowest primary school enrollment rate.

Since those goals were set, the area that includes roughly 1 billion people made considerable progress improving the living conditions for many people. But as the UN looks to adopt new goals for the next 15 years, sub-Saharan Africa still lags behind other developing regions, particularly in the areas of poverty, health care and education.

Since those goals were set, the area that includes roughly 1 billion people made considerable progress improving the living conditions for many people. But as the UN looks to adopt new goals for the next 15 years, sub-Saharan Africa still lags behind other developing regions, particularly in the areas of poverty, health care and education.

This reality for many in Africa comes through in the recent Pew Research Center survey of 9,062 people across nine sub-Saharan African countries, which found that medians of at least eight-in-ten say these three issues are the most pressing challenges for their country.

Many of the countries surveyed in sub-Saharan Africa have seen some of the world’s highest economic growth rates in the past decade, which has led to high levels of economic optimism for the future. Yet a median of 88% still say that a lack of job opportunities is a very big problem in their country.

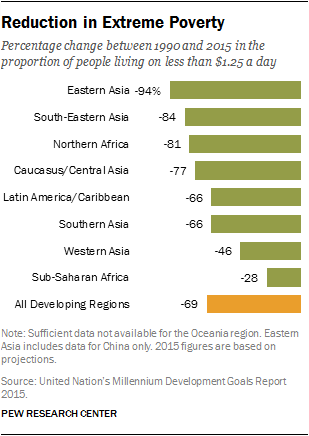

Indeed, sub-Saharan Africa made the least progress among all developing regions toward reducing extreme poverty since 1990 (the reference date for the goals set in 2000). Today, the percentage of people living on less than $1.25 a day in sub-Saharan Africa (41%) is more than twice as high as any other region (such as Southern Asia, with 17%).

Indeed, sub-Saharan Africa made the least progress among all developing regions toward reducing extreme poverty since 1990 (the reference date for the goals set in 2000). Today, the percentage of people living on less than $1.25 a day in sub-Saharan Africa (41%) is more than twice as high as any other region (such as Southern Asia, with 17%).

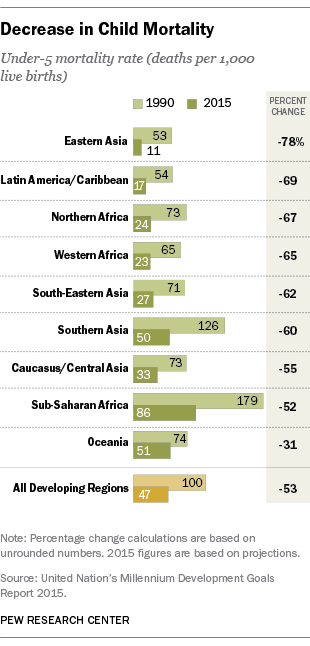

Health care has also remained a key challenge in sub-Saharan Africa. Roughly eight-in-ten (median of 82%) across the nine countries surveyed say poor-quality health care is a very big problem in their nation. On this issue, sub-Saharan Africa lags far behind other areas of the world on key indicators such as the mortality rates for children under 5 and for mothers.

Between 1990 and 2015, sub-Saharan Africa decreased the number of deaths among children under 5 by 52%. Even so, the region continues to have the highest under-5 mortality rate, with 86 deaths per 1,000 live births. And while maternal deaths dropped by 49% since 1990, sub-Saharan Africa still has a maternal mortality rate more than twice that of any other region (510 per 100,000 live births in sub-Saharan Africa compared with 190 in Southern Asia, the next-highest).

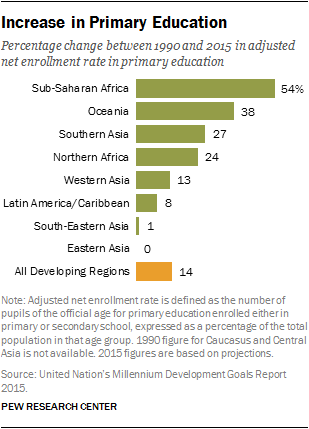

When it comes to education, sub-Saharan Africa stands out for making the biggest improvement in access to education since 1990 compared with other regions of the world. The proportion of children enrolled in primary or secondary school increased by 54% over the past 25 years.

When it comes to education, sub-Saharan Africa stands out for making the biggest improvement in access to education since 1990 compared with other regions of the world. The proportion of children enrolled in primary or secondary school increased by 54% over the past 25 years.

Nonetheless, the region has not caught up with other parts of the globe. Every other developing region has reached roughly 95% net enrollment or higher, compared with 80% in sub-Saharan Africa. Perhaps not surprisingly, our poll finds that a median of 81% across the nine countries surveyed in this region say poor-quality schools are a major domestic problem.

Another key part of the UN’s goals was a commitment worldwide to develop a global partnership for development. On this objective, net official development assistance from member countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development increased by 66% between 2000 and 2014. But this increase seems to have leveled off after 2013. Possibly because of the magnitude of the challenges they continue to face, a median of 68% across the nine African countries surveyed by Pew Research Center say their nation needs more foreign aid than it receives today.

Note: For more on progress toward the UN’s Millennium Development Goals by country and region, see the UN’s Millennium Development Goals Report 2015.