SPOILER ALERT: If you haven’t already done so, test yourself with our new Science Knowledge Quiz.

There is a significant gap in knowledge about scientific concepts along racial and ethnic lines in the U.S., according to a new Pew Research Center report released last week.

There is a significant gap in knowledge about scientific concepts along racial and ethnic lines in the U.S., according to a new Pew Research Center report released last week.

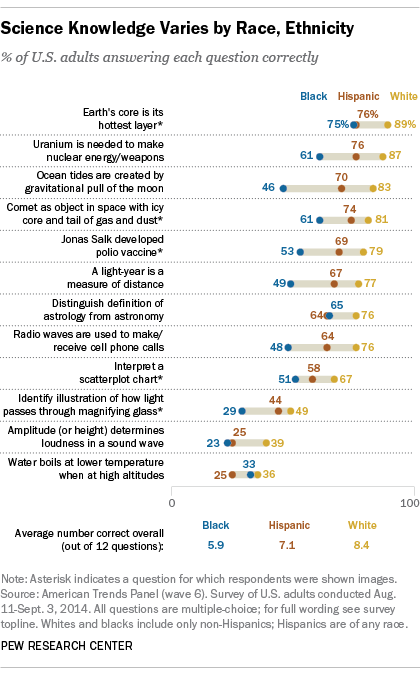

When asked a series of 12 science-related questions, whites, on average, fared better than blacks or Hispanics. While the average number of questions whites answer correctly is 8.4, for Hispanics that number is lower – 7.1 – and drops to 5.9 for blacks. (There were not enough Asian respondents in the sample to be broken out into a separate analysis.)

Our latest findings are consistent with previous Pew Research surveys and with data from the General Social Survey (GSS) conducted by the National Opinion Research Center. These differences tend to span multiple scientific disciplines, from life and earth sciences to physics and energy-related questions.

But why is this? Research suggests there might be several factors at play, and they often are interconnected. Educational attainment – such as the different shares of blacks and whites to have college degrees – may be one. Another issue might relate to the underrepresentation of blacks and Hispanics in the STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) workforce. And access to science information may also play a role in how well people cultivate an understanding of the subject.

Our report finds that, overall, Americans with more formal education fare better on science-related questions. Whites are more likely than blacks and Hispanics to hold a bachelor’s or advanced degree and whites also make up a larger share of science and engineering bachelor’s degree recipients. Some 63% of science and engineering degrees awarded in 2011 went to white students, compared with roughly 10% to Hispanics and 9% to blacks, according to a report by the National Science Board.

But there’s evidence that differences among racial and ethnic groups are seen at the elementary and high school level, too. Although achievement test gaps have narrowed somewhat over time, in general, black and Hispanic students continue to perform lower than whites and Asians on standardized tests. For example, among eighth graders, the average science score on the 2011 National Assessment of Educational Progress test was 152. Blacks’ and Hispanics’ average scores are lower, 129 and 137, while whites (163) and Asians and Pacific Islanders (159) fared better than the national average. According to another report, black and Hispanic high school students also are less likely than whites or Asians to take advanced science courses.

Mark Berends, a sociology professor at the University of Notre Dame, said if performance gaps persist throughout students’ academic careers, it follows that you could see disparities persist in higher education, employment and knowledge of certain subjects. Berends also explained that parents’ comfort level with science may influence how much interest a child shows in the subject. “A parent’s education level and familiarity with scientific subjects help bring kids’ imagination to life,” he said.

Another related factor may be that blacks and Hispanics are less likely to work in scientific fields. That might mean they have less exposure to scientific research and information. Historically, the fields of science, technology, engineering and mathematics have been predominately white and male and there is considerable effort in recent years to create initiatives encouraging a more diverse STEM workforce.

Cheryl Leggon, associate professor in the School of Public Policy at Georgia Institute of Technology, believes that this lack of diversity may influence blacks’ and Hispanics’ interest in science and science careers. “If we see someone that looks like us, then it does have an impact on us, in terms of our interest,” Leggon said. Greater diversity in these fields may give blacks and Hispanics a sense that a career in science could be a viable option for them, she said.

Even with efforts to improve diversity in STEM fields, blacks and Hispanics are consistently underrepresented. According to a 2013 U.S. Census Bureau report, blacks made up 11% of the total workforce in 2011, yet they only occupied 6% of STEM jobs. A similar pattern is seen with Hispanics, who make up 15% of the overall labor force, but held 7% of jobs related to STEM fields.

The census report also found that whites and Asians are overrepresented in the STEM workforce when compared with their total workforce populations. About two-thirds (67%) of the total workforce was white in 2011, but whites made up a higher share of STEM employees, at 71%. For Asians, the difference is larger: 15% of STEM workers were Asian, compared with 6% of the overall workforce.

Eric Plutzer, a political science professor at the Pennsylvania State University, said one factor is the “complex relationship between science and the African-American community.” Plutzer, who wrote about racial gaps in attitudes about science, explained that the legacy of the Tuskegee and Henrietta Lacks experiments are often in the background when it comes to African Americans’ confidence in science professionals and institutions. His analysis of GSS survey data found that while 45% of white adults express a great deal of confidence in the people running the scientific community, that share falls to 31% for blacks.

Lower literacy rates among black and Hispanic adults may also contribute to the ability to correctly answer science knowledge questions. These groups’ relatively low participation rates in clinical trials could be another factor that affects familiarity with scientific issues, while cultural dynamics, including language barriers, also may contribute to disparities in science knowledge.

Shirley Malcom, director of education and human resources programs at the American Association for the Advancement of Science, said that science reporting in the Spanish language is not as widely available as it is in English media, which may hinder some people from obtaining information about science.

Malcom also suggested that racial disparities in science knowledge is not about a lack of interest by blacks and Hispanics, but has more to do with access to information. She said the scientific community and science news media could reach out more to these communities to help make science “more accessible and relevant to their lives.”