Even before the Supreme Court’s decision granting same-sex couples a constitutional right to wed, legal scholars and others have been trying to determine how such a ruling might affect religious institutions. It has been a question on the minds of the justices, too.

Indeed, during the April 28 oral arguments in the case, Obergefell v. Hodges, most of the justices asked about or commented on this issue. Justice Samuel Alito drew a possible parallel with Bob Jones University, a fundamentalist Christian institution that lost its nonprofit, tax-exempt status in 1983 as a result of its policy banning interracial marriage and dating.

If the court ruled in favor of gay marriage, “would the same apply to a university or college if it opposed same-sex marriage?” Alito had asked Solicitor General Donald Verrilli, who was arguing on behalf of the government in favor of gay marriage. “It is going to be an issue,” Verrilli answered.

Virtually everyone agrees that the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution offers some protections for religious groups. For example, most (even among gay rights advocates) believe the Constitution protects clergy from being required to officiate at marriages for same-sex couples and churches from being forced to allow gay and lesbian couples to marry in their sanctuaries.

But what about a church basement or retreat center, which is rented out for opposite-sex weddings? And what about a religiously affiliated institution, like a university, that offers married heterosexual students housing but refuses such accommodation for married gay and lesbian students?

These questions have real-world implications, since virtually all American religious groups have affiliated nonprofits (such as schools, hospitals and charities). And many, including some evangelical Protestant denominations, the Catholic Church, the Mormon church and Orthodox Jewish groups, oppose gay marriage on religious grounds.

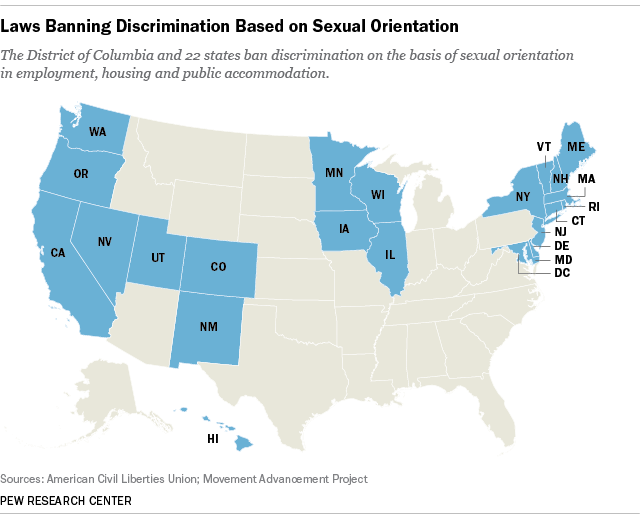

Some scholars believe that the ruling in favor of gay marriage will not lead to widespread acrimony and legal battles. They note, for example, that there is no federal law banning discrimination based on sexual orientation. And, of the 22 states that ban discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, a majority (13) have at least some protections for religious groups written into their anti-discrimination statutes.

“There’s a big difference between something that could be an issue and something that’s likely to be an issue,” says Robert Tuttle, who teaches religion and law at George Washington University. Tuttle says he believes there may be some lawsuits, but he predicts that in more cases than not, accommodation and compromise are likely to win out. “After all, we still allow institutions, like universities, to discriminate based on gender,” he says.

But University of Illinois law professor Robin Fretwell Wilson says it’s possible that institutions will be pressured to give ground on gay marriage by federal authorities (such as the Internal Revenue Service, which could take away an institution’s tax-exempt status), state civil rights commissions or private lawsuits. She notes, for example, that the federal government now reads its laws against sex discrimination “to include sexual orientation discrimination, which opens a whole layer of potential threat” to religious organizations.

And yet she also says it is possible that all sides will “be able to live in peace,” noting a recent compromise in Utah, “where you saw an extension of gay rights in exchange for religious protections.”

Note: This is an update of a post published on June 25, 2015.

Related: Timeline: Same-sex marriage, state by state

5 facts about same-sex marriage