A new research paper suggests that the number of married same-sex couples in the United States in 2013 may have been much lower than the Census Bureau’s initial estimate for that year.

The bureau’s 2013 American Community Survey, published last year, had estimated there were 252,000 married same-sex couples in the U.S. But the bureau at the time acknowledged this was an overcount, which it blamed largely on heterosexual married couples who mistakenly checked the wrong gender box on the survey questionnaire.

Census Bureau researcher Daphne Lofquist said in a poster and brief write-up she presented at this year’s Population Association of America conference that only about 170,000 of the 252,000 first reported – about 68% – were likely married same-sex couples. The others either were not same-sex married couples or their status could not be determined.

Why does the Census Bureau need to get this right? For a number of reasons. Growth in the number of same-sex married couples is fueling demand from government officials, researchers and advocates for good data about them. Same-sex marriage is now legal in 36 states and the District of Columbia, yet states are inconsistent in how they track such information, and some couples marry abroad.

The data offer a gauge of how society is changing and can help officials estimate demand for benefits based on marital status. The U.S. Supreme Court is expected to hand down a key ruling on its legality by the end of its current session this month, which could have major policy implications for gay couples going forward.

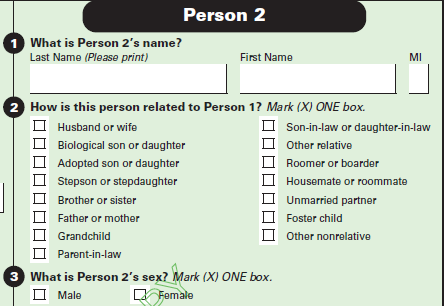

The Census Bureau estimates the number of same-sex married couples by using respondents’ answers to two questions: one about their sex and the second about their relationship status. The relationship question asks how each person in the household is related to the householder (the person who fills out the questionnaire). Current options include “husband or wife,” “unmarried partner” and more than a dozen other categories. If someone checks “husband or wife” and is the same sex as his or her spouse, the bureau counts them in a same-sex marriage.

To estimate the amount of error in the 2013 estimate, Lofquist used a list developed by the bureau of first names, categorized by sex, to determine the gender of survey respondents with clearly male or female names. (The list excludes first names of uncertain gender, such as “Lee.”)

Lofquist reported one potentially encouraging finding: People who answered the survey online had lower error rates than those who answered by mail or whose responses were filled in by interviewers. That could be good news, because the bureau is pushing to have most people provide their own responses online. However, she acknowledged that the kind of people who respond online may be less error-prone no matter what their response mode, so it is unclear whether the online mode itself reduced mistakes.

The agency hoped for better results from an experiment using a new version of the relationship question – but a second new research paper reports that this did not solve the problem either.

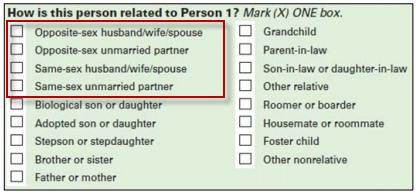

Instead of offering just “husband or wife” as categories that people could choose to describe their relationship, the bureau tried substituting “opposite-sex husband/wife/spouse” and “same-sex husband/wife/spouse.”

The experimental question reduced inaccuracy when it was used on the bureau’s 2013 American Housing Survey, but last year, the bureau reported that more than half of same-sex married couples counted in survey had mismatched answers to the sex and relationship questions.

The new paper concluded that this inconsistency “is driven by errors on relationship rather than sex” – that is, opposite-sex couples were identifying themselves as same-sex couples on the relationship question. Couples marked as same-sex spouses were 1,000 times more likely than those marked as opposite-sex spouses to mismark the new relationship question.

One mystery in the new research is that because the housing survey is done by computer-assisted interviewing, it could not be determined whether interviewers or respondents made the mistakes. Bureau researchers suggested that they could reduce errors by using improved interview software or better interviewer training.

Meanwhile, the revised relationship question will be asked in a test census sent to 1.2 million U.S. households later this year, and bureau researchers hope to learn more about how it performs.