Over the course of history, many scientists and activists have raised alarm about population numbers that only increase every year.

When the English scholar Thomas Malthus published An Essay on the Principle of Population in 1798, the number of people around the world was nearing 1 billion for the first time. “The power of population is indefinitely greater than the power in the earth to produce subsistence for man,” he wrote then.

Skip ahead to 1968, when the world’s population had risen to around 3.5 billion and the annual rate of growth peaked at 2.1%: American biologist Paul Ehrlich revisited the Malthusian principle in his bestseller The Population Bomb, starting a movement to hedge the trend. “The basic point is so simple,” Ehrlich told Retro Report. “We have a finite planet with finite resources. In such a system, you can’t have infinite population growth.”

Skip ahead to 1968, when the world’s population had risen to around 3.5 billion and the annual rate of growth peaked at 2.1%: American biologist Paul Ehrlich revisited the Malthusian principle in his bestseller The Population Bomb, starting a movement to hedge the trend. “The basic point is so simple,” Ehrlich told Retro Report. “We have a finite planet with finite resources. In such a system, you can’t have infinite population growth.”

In 2015, the global population is an estimated 7.3 billion, according to the United Nations, and many of Malthus’s and Ehrlich’s predictions have yet to come true or have been proven false (such as the “increasing” death rate, which has actually decreased).

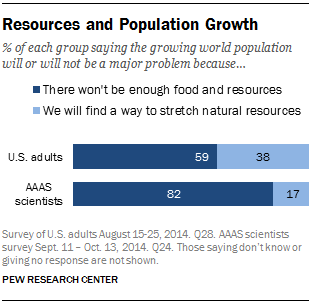

According to a pair of 2014 Pew Research Center surveys, however, today’s scientists are more likely than the general American public to be concerned about population growth, though not necessarily to the extent that Malthus and Ehrlich were.

Asked whether or not the growing world population will be a major problem, 59% of Americans agreed it will strain the planet’s natural resources, while 82% of U.S.-based members of the American Association for the Advancement of Science said the same. Just 17% of AAAS scientists and 38% of Americans said population growth won’t be a problem because we will find a way to stretch natural resources.

Asked whether or not the growing world population will be a major problem, 59% of Americans agreed it will strain the planet’s natural resources, while 82% of U.S.-based members of the American Association for the Advancement of Science said the same. Just 17% of AAAS scientists and 38% of Americans said population growth won’t be a problem because we will find a way to stretch natural resources.

Americans used to be much less concerned about population growth, according to Gallup polls: In 1959, three-quarters (75%) of Americans had heard about the “great increase in population” predicted for the world during the coming decades, but just 21% of Americans said they were worried about it. And when comparing population concerns with a list of global threats, a 1997 Pew Research Center poll showed that Americans were more worried about other potential risks.

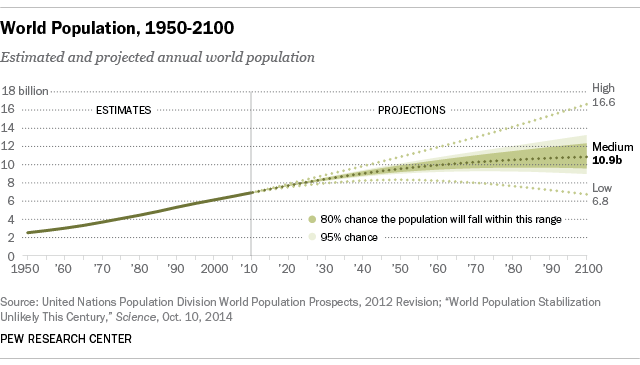

Looking ahead, it’s still unclear what the population trajectory will be. The UN says that population will continue to grow throughout the 21st century, predicting with 80% confidence that it will reach somewhere between 9.6 billion and 12.3 billion people by 2100.

Growth is expected to occur mostly in Africa, and abate in the Americas, Europe and parts of Asia, especially as families in more-developed nations have fewer children than they used to have. In many countries in the latter regions, the total fertility rate has dropped below the “replacement rate” of about 2.1 lifetime births per woman. The total fertility rate in the U.S., for example, fell to 1.86 in 2013.

This leads to yet another population worry over whether there are enough young people to take care of the older populations, as lifespans continue to increase and fertility decreases in certain parts of the world. Concerns about this issue are more common in Japan, South Korea, China, Germany and Spain, according to our 2013 global survey. The demographic future for the U.S. and the world looks very different than the recent past. Growth from 1950 to 2010 was rapid—the global population nearly tripled, and the U.S. population doubled. However, population growth from 2010 to 2050 is projected to be significantly slower and is expected to tilt strongly to the oldest age groups, both globally and in the U.S.

Global Population Estimates by Age, 1950-2050