The Mexican government has deported a record number of Central American children traveling without a guardian since last fall, which President Obama and other U.S. officials say has contributed to a significant drop in children apprehended at the U.S.-Mexico border.

The Mexican government has deported a record number of Central American children traveling without a guardian since last fall, which President Obama and other U.S. officials say has contributed to a significant drop in children apprehended at the U.S.-Mexico border.

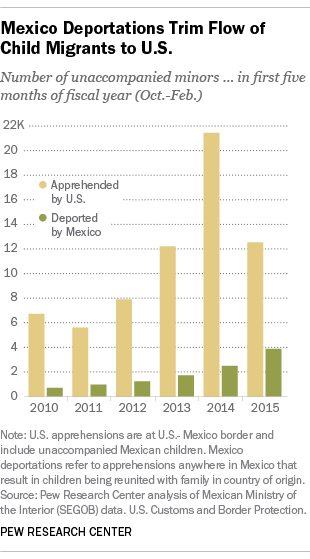

Mexico’s 3,819 deportations of unaccompanied minors from Central America during the first five months of the fiscal year represent a 56% increase over the same period a year earlier, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of Mexican and U.S. government data. The stepped up security was a result of a plan by Mexican officials to address the record surge in child migrants last year.

Overall, U.S. officials apprehended 12,509 unaccompanied children at the U.S.-Mexico border in the first five months of the fiscal year that began in October, down from 21,403 over the same time period a year ago. (Most children apprehended during this fiscal year — 7,771 — came from the Central American countries of El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras, with nearly all of the rest coming from Mexico.)

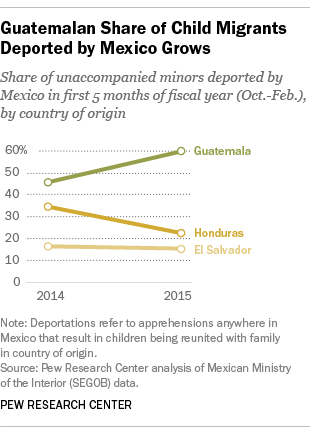

The Mexican data also show changes in terms of where the unaccompanied children are traveling from this year compared with last. Guatemalan children now comprise a higher share of deportations, as their numbers have doubled in the first five months of this fiscal year compared with the same period a year ago. In addition, the number of Salvadoran children deported has increased by 49% over the same time period, while the number of Honduran children is similar to the previous year.

The Mexican data also show changes in terms of where the unaccompanied children are traveling from this year compared with last. Guatemalan children now comprise a higher share of deportations, as their numbers have doubled in the first five months of this fiscal year compared with the same period a year ago. In addition, the number of Salvadoran children deported has increased by 49% over the same time period, while the number of Honduran children is similar to the previous year.

Last summer’s surge in apprehensions by U.S. authorities of unaccompanied minors at the U.S.-Mexico border was due to dramatic increases from all three Central American countries. Among all children apprehended, 27% were from Honduras, 25% from Guatemala and 24% from El Salvador. Last year, many unaccompanied children apprehended at the U.S.-Mexico border had fled violence in Honduras and El Salvador. (Guatemalan unaccompanied minors were more likely to leave for economic reasons.)

In the first five months of this fiscal year, though, Guatemalans account for more than one-third (35%) of unaccompanied children apprehended in the U.S., compared with 18% from El Salvador and 9% from Honduras.

In addition to the Mexican government’s record number of deportations, there are other possible reasons for this year’s decline in children attempting to cross the U.S.-Mexico border. The decrease in apprehensions comes as the U.S. government has sped up the processing of immigration court cases for unaccompanied minors and launched public information campaigns in Central America to discourage children from trying to cross into the U.S. At the same time, a new program allows some immigrants here illegally who have obtained relief from deportation (such as Salvadorans and Hondurans with Temporary Protected Status) to apply for their children to join them in the U.S. as refugees or asylum seekers. To date, no applications for this program have been approved.

In addition, homicide rates are declining in some of the Central American countries. In Honduras, where drug-related violence has been a problem, the homicide rate in 2012 was at around 86 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants, the highest for any country in the world. In 2014, the rate had dropped to 68 per 100,000, although the country still has one of the world’s highest homicide rates.