America’s complicated, conflicted relationship with the death penalty is once more in the news, for a couple of reasons. First, the penalty phase for convicted Boston Marathon bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev began this week. Although Massachusetts abolished capital punishment in 1984, Tsarnaev is being tried in federal court, where the death penalty is still an option for more than 40 federal crimes. Next week, the Supreme Court will hear arguments in Glossip v. Gross, in which three prisoners on Oklahoma’s death row are challenging the constitutionality of that state’s three-drug execution protocol.

While a majority of Americans continue to favor the death penalty for people convicted of murder – 56%, according to a new Pew Research Center survey – far fewer people are receiving death sentences nowadays than in years past. As a result, fewer U.S. prisoners are facing the possibility of execution than at any time in the past two decades.

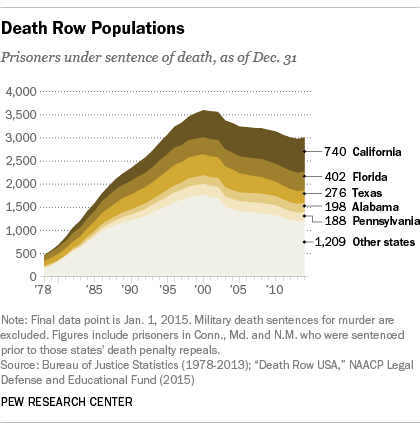

Though the number fluctuates almost daily, there are roughly 3,000 inmates on the nation’s death rows. An annual report from the Bureau of Justice Statistics put the total death row population at 2,979 as of Dec. 31, 2013. (A quarterly reckoning by the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund put the number at 3,019 as of Jan. 1, 2015, using somewhat different methodology.)

Either way, there are about 600 fewer prisoners now than there were at the end of 2000, when the total death row population peaked following steady growth since 1976 (when the Supreme Court effectively reinstated capital punishment).

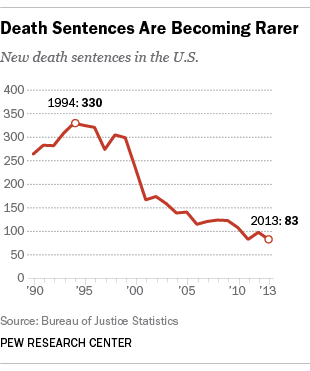

About the same time as public support for the death penalty began to fall, so did the number of newly imposed death sentences – slowly at first, then accelerating around the turn of the 21st century: From 2001 through 2013, an average of 126 prisoners were sent to death row each year. In 2013, the most recent year for which data are available, just 83 inmates were sent to state and federal prisons under sentence of death, tied for the smallest number of death row admissions since 1973 (when there were 44). Also in 2013, 45 condemned prisoners had their sentences or convictions overturned; 39 were executed; and 31 died in prison from some other cause.

About the same time as public support for the death penalty began to fall, so did the number of newly imposed death sentences – slowly at first, then accelerating around the turn of the 21st century: From 2001 through 2013, an average of 126 prisoners were sent to death row each year. In 2013, the most recent year for which data are available, just 83 inmates were sent to state and federal prisons under sentence of death, tied for the smallest number of death row admissions since 1973 (when there were 44). Also in 2013, 45 condemned prisoners had their sentences or convictions overturned; 39 were executed; and 31 died in prison from some other cause.

The 1990s, it turns out, were a high-water mark both in support for the death penalty (which peaked at 78% in 1996) and in imposing it: An average of 293 people entered death row each year from 1990 through 2000.

Most of the 32 death-penalty states have fewer people on their death rows now than they did in the peak year of 2000. The big exception is California, where dozens of convicted criminals have been sentenced to death in recent years (25 in 2013) but no one has been executed since 2006, when court rulings forbade the state from using its three-drug lethal-injection protocol. According to the Los Angeles Times, as of last month 751 inmates were on California’s death row, by far the most of any state; since the last execution, 49 of these inmates have died in prison of other causes. As the state’s main death row facility at San Quentin State Prison nears capacity, Gov. Jerry Brown has proposed spending $3.2 million to make more cells available.

The other notable exception to the trend of smaller death rows: the federal government. In 2000, only 20 prisoners were facing federal death sentences. That figure has more than tripled since, to 62 as of the beginning of this year, according to the NAACP report.

Who’s on death row? According to the BJS data, 56% of prisoners under sentence of death at the end of 2013 were white and 42% were black; 14% were of Hispanic origin. All but 56 were men. About two-thirds had at least one prior felony conviction, and 28% were on probation or parole at the time of their capital offense, though blacks and Hispanics were more likely to have been on probation or parole (31% and 32%, respectively) than whites (24%). On average, the inmates had spent 14.6 years on death row.