Stocks have been the most robust component of the nation’s up-to-recently spotty recovery from the Great Recession. Broad indices such as the Dow Jones Industrial Average and the Standard & Poor’s 500 have long since surpassed their pre-crash highs. Even the technology-heavy Nasdaq composite, which plunged during the dot-com bust and remained depressed for years afterward, is close to the all-time high it set back in March 2000.

Small wonder, then, that 31% of Americans say the stock market has fully recovered from the recession, according to a recent Pew Research Center survey, and 47% say it has partially recovered. Overall, more Americans see full or partial recovery in stocks than in any other aspect of the economy we asked about (jobs, incomes, real estate).

Stock ownership (both direct and indirect, through retirement accounts and mutual funds) is heavily concentrated among wealthier households, and many Americans haven’t benefited from the rising markets. But according to our analysis, even stockholders haven’t benefited as much as their account statements might indicate. Stock prices and index values seldom are adjusted for inflation, which means investors and observers may have an exaggerated sense of the stock market’s real-world performance.

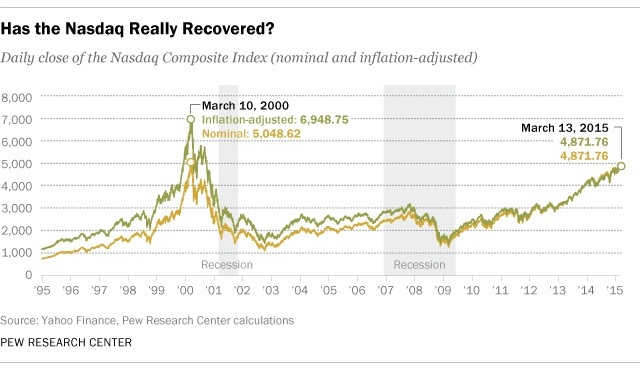

Take that Nasdaq news, for instance. (We looked at the Nasdaq because, among widely followed stock-market metrics, it’s taken the longest to recover; the Dow and the S&P 500 have long since set new record highs, at least in nominal terms.)

On a nominal basis, the Nasdaq peaked at 5,048.62 on March 10, 2000, powered by such erstwhile tech giants as Worldcom, Global Crossing and Netscape. After a steep plunge, a long, slow recovery, then another plunge during the 2008-09 financial crisis, the Nasdaq has been on a tear – up 282% since March 2009, and making headlines earlier this month when it closed above 5,000 for the first time since 2000. (It’s fallen back somewhat since then, however.)

But factor in inflation, and the picture isn’t quite as rosy. We used the Consumer Price Index to adjust each day’s Nasdaq closing value; seen that way, the index is still 30% below its all-time high. (Our analysis didn’t include the impact of dividend payments.)

To be sure, inflation hasn’t been much of a factor lately. As measured by the CPI, consumer inflation has been running below an annualized 2% for most of the past three years. In January, the last month for which data are available, the CPI was actually 0.1% below its level a year earlier. (February’s inflation report is due out March 24.)

But over time, the effects of inflation can be considerable: Over the past two decades, for example, the Nasdaq composite index is up 555% on a nominal basis, but “just” 320% after adjusting for inflation. Since most Americans who own stock do so inside retirement accounts (49.2% of families have such accounts, while just 13.8% own stocks directly, according to the Federal Reserve’s 2013 Survey of Consumer Finances), they’re presumptively long-term investors for whom inflation ought to be a consideration.