Americans like to complain about holiday-season shopping: In a Pew Research Center survey conducted last year, people’s three least-favorite things about the holidays were commercialism, holiday-related expenses and crowds in the malls and stores. But they sure do a lot of it anyway. The same survey found that 86% of adults planned to buy gifts for friends and family, and according to the Census Bureau’s Monthly Retail Trade Report, retail sales last December totaled $437.1 billion.

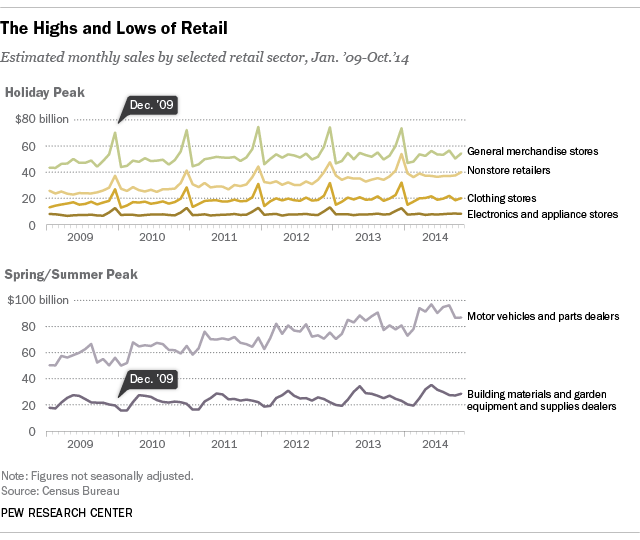

Holiday sales reliably spike in December for a number of retail categories, according to the census data — notably department stores and other general-merchandise stores; clothing and accessories stores; electronics and appliance stores; and e-commerce sites, catalog companies and other “non-store retailers.” While other types of retailers (such as home-improvement stores and car dealers) exhibit different seasonal sales patterns, overall U.S. retail sales are tilted toward the holiday season: November-December 2013 sales made up 18.14% of sales for all of 2013, according to the census data.

For all that, the holidays aren’t quite as important to retailers as they used to be. In 1993, according to the Census data, November-December sales accounted for 19.41% of full-year sales. Since then, the November-December share has mainly drifted lower (not counting the disastrous 2008 holiday shopping season, which came as the U.S. economy tumbled into the Great Recession).

Most, but not all, retailers rely on the holiday season for a significant chunk of their sales. To get a better sense of how important the holidays are, or aren’t, we analyzed more than five years’ worth of quarterly financial data from 20 major retail companies, running the gamut from Wal-Mart and Family Dollar to Coach and Ralph Lauren. Since most retailers’ fiscal years don’t align with the calendar year, we adjusted each company’s data to map the fiscal quarter that included the holidays onto the fourth quarter of each calendar year.

Most, but not all, retailers rely on the holiday season for a significant chunk of their sales. To get a better sense of how important the holidays are, or aren’t, we analyzed more than five years’ worth of quarterly financial data from 20 major retail companies, running the gamut from Wal-Mart and Family Dollar to Coach and Ralph Lauren. Since most retailers’ fiscal years don’t align with the calendar year, we adjusted each company’s data to map the fiscal quarter that included the holidays onto the fourth quarter of each calendar year.

As it turns out, the retailer that derived the highest percentage of sales from the holiday quarter wasn’t, as you might guess, Tiffany’s or L Brands (the parent of Victoria’s Secret and Bath & Body Works). It was GameStop, the video- and computer-game company with nearly 4,500 stores across the U.S. and 2,200 in 14 other countries. In its most recent fiscal year, which ended Feb. 1, nearly 41% of GameStop’s sales (and 62% of its net profit) came from the November-through-January quarter. GameStop is even more dependent on holiday sales now than it was in 2009, when 39% of its sales occurred in that quarter.

But for many of the retailers we studied, the holiday season has diminished in importance. At Amazon, for example, holiday-quarter sales accounted for nearly 39% of total sales in 2009 but just 34.4% last year. Barnes & Noble’s holiday share fell from almost 36% in 2009 to 31.5% in 2013; Coach’s went from nearly 32% to 28.5%. And at the parent of Ann Taylor, the holiday quarter is just like any other, accounting for 25% to 26% of annual sales each year we studied.

All that said, of course, hand-wringing about the commercialization of the holidays goes back a long time, and by now is almost as much a seasonal tradition as eggnog, latkes and endless loops of “I Saw Mommy Kissing Santa Claus.” As satirist