Congress is back from its Thanksgiving break to continue its “lame duck” session — so called because it includes senators and representatives who lost their seats in last month’s elections but whose terms won’t expire till January. Among the items on the congressional to-do list: keeping the government funded, extending an assortment of expired tax breaks, and voting on nominees for ambassadorships, judgeships and other offices.

Congress is back from its Thanksgiving break to continue its “lame duck” session — so called because it includes senators and representatives who lost their seats in last month’s elections but whose terms won’t expire till January. Among the items on the congressional to-do list: keeping the government funded, extending an assortment of expired tax breaks, and voting on nominees for ambassadorships, judgeships and other offices.

We wondered, how productive are these lame duck sessions, and is the “lame” part of the tag deserved?

Our analysis found that lame duck sessions are shouldering more of the legislative workload than they used to. The last Congress’ lame duck, which stretched from November 2012 past New Year’s Day 2013, passed only 87 public laws, but that was 30.7% of the Congress’ entire two-year output and 31.3% of its substantive output (that is, excluding post-office renamings, National “fill-in-the-blank” Week designations and other purely ceremonial legislation). In 2010, the 99 public laws passed during the 111th Congress’ lame duck session accounted for 25.8% of all that Congress’ laws (and 29.2% of its substantive laws).

Our analysis found that lame duck sessions are shouldering more of the legislative workload than they used to. The last Congress’ lame duck, which stretched from November 2012 past New Year’s Day 2013, passed only 87 public laws, but that was 30.7% of the Congress’ entire two-year output and 31.3% of its substantive output (that is, excluding post-office renamings, National “fill-in-the-blank” Week designations and other purely ceremonial legislation). In 2010, the 99 public laws passed during the 111th Congress’ lame duck session accounted for 25.8% of all that Congress’ laws (and 29.2% of its substantive laws).

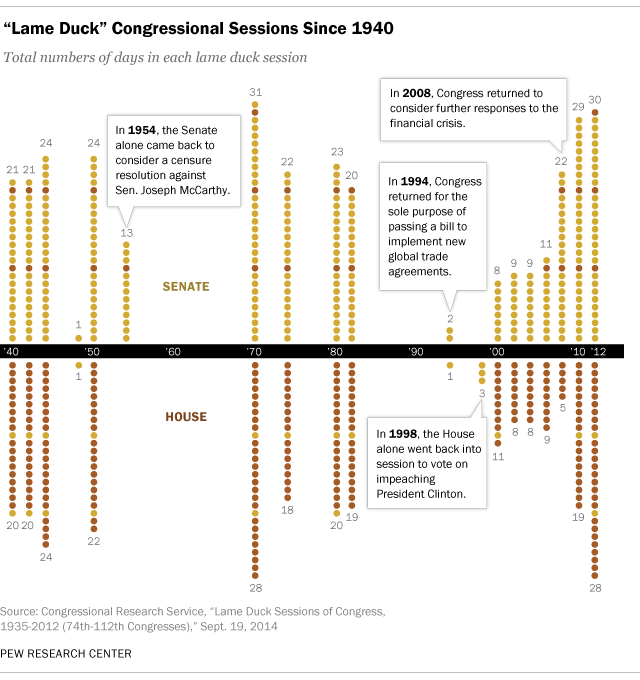

Those figures are up compared with recent history. Looking at the eight full lame duck sessions that were held between 1974 and 2008, on average they accounted for about 18% of the legislative output of their respective Congresses. (The sessions themselves averaged 30.25 calendar days, or 4% of a two-year congressional term, though legislative business wasn’t transacted on every day.)

But those averages obscure considerable variation in lame-duck productivity, which can be measured in several ways.

In terms of sheer volume, the 96th Congress’ lame duck session in November-December 1980 takes first place: It passed a total of 196 laws over 23 session days, among them the Superfund environmental-cleanup law, an Alaska public-lands law, and a law governing electric-power planning in the Pacific Northwest.

Of course, not all laws are equally significant. Looking just at substantive laws, the lame duck session held after the November 1974 election comes out on top, with 138 substantive laws enacted. The unfolding Watergate scandal, and the ensuing collapse of the Nixon-Agnew administration, had so consumed Congress’ attention that much major legislation had been sidelined, according to a detailed Congressional Research Service report on lame duck sessions. The 1974 lame duck Congress enacted the Safe Drinking Water Act and a federal Privacy Act, and ensured that the government, rather than Nixon, retained control over his tapes.

Based just on the numbers, the lame duck session of November-December 2006 made the most efficient use of its time: In just 11 session days (excluding holidays, weekends and other days in which neither the House nor the Senate formally convened) it passed 115 laws, or an average of 10.5 per session day. Those laws, however, didn’t include the main items on the Congress’ unfinished-business list: 11 of 13 appropriations bills. Instead, Congress funded the government through continuing resolutions, a pattern that has recurred more than once since.

Based just on the numbers, the lame duck session of November-December 2006 made the most efficient use of its time: In just 11 session days (excluding holidays, weekends and other days in which neither the House nor the Senate formally convened) it passed 115 laws, or an average of 10.5 per session day. Those laws, however, didn’t include the main items on the Congress’ unfinished-business list: 11 of 13 appropriations bills. Instead, Congress funded the government through continuing resolutions, a pattern that has recurred more than once since.

Two other lame ducks stand out as short but significant. In 1994, the House and Senate reconvened for the sole purpose of voting on a bill to implement the Uruguay Round of trade negotiations, which among other things created the World Trade Organization; the House was in session for just one day, the Senate for two. And in 1998, the House alone came back to impeach President Clinton and appoint managers for his Senate trial; the only other thing it did in its three-day session was pass a resolution supporting U.S. troops in the Persian Gulf.

Lame duck sessions were standard before the 20th Amendment, ratified in 1933, which moved the starting date for a new Congress from March 4 to January 3. Afterward they were very uncommon (aside from the years during and just after World War II). But as political polarization and legislative gridlock have increased in recent years, lame duck sessions have become a normal part of the political calendar: The past nine Congresses all have come back for post-election legislating.