The question of whether libertarianism is gaining public support has received increased attention, with talk of a Rand Paul run for president and a recent New York Times magazine story asking if the “Libertarian Moment” has finally arrived. But if it has, there are still many Americans who do not have a clear sense of what “libertarian” means, and our surveys find that, on many issues, the views among people who call themselves libertarian do not differ much from those of the overall public.

The question of whether libertarianism is gaining public support has received increased attention, with talk of a Rand Paul run for president and a recent New York Times magazine story asking if the “Libertarian Moment” has finally arrived. But if it has, there are still many Americans who do not have a clear sense of what “libertarian” means, and our surveys find that, on many issues, the views among people who call themselves libertarian do not differ much from those of the overall public.

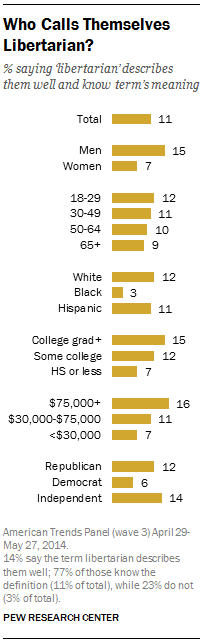

About one-in-ten Americans (11%) describe themselves as libertarian and know what the term means. Respondents were asked whether the term “libertarian” describes them well and — in a separate multiple-choice question — asked for the definition of “someone whose political views emphasize individual freedom by limiting the role of government”; 57% correctly answered the multiple-choice question, choosing “libertarian” from a list that included “progressive,” “authoritarian,” “Unitarian” and “communist.” On the self-description question 14% said they were libertarian. For the purpose of this analysis we focus on the 11% who both say they are libertarian and know the definition of the term.

These findings come from the Pew Research Center’s political typology and polarization survey conducted earlier this year, as well as a recent survey of a subset of those respondents via the Pew Research Center’s new American Trends Panel, conducted April 29-May 27 among 3,243 adults.

Self-described libertarians tend to be modestly more supportive of some libertarian positions, but few of them hold consistent libertarian opinions on the role of government, foreign policy and social issues.

Men were about twice as likely as women to say the term libertarian describes them well and to know the meaning of the term (15% vs. 7%). More college graduates (15%) than those with no more than a high school education (7%) identified as libertarians. There also were partisan differences; 14% of independents and 12% of Republicans said they are libertarian, compared with 6% of Democrats.

Some of these differences arise from confusion about the meaning of “libertarian.” Just 42% of those with a high school education or less answered the multiple-choice question correctly, compared with 76% of college graduates.

In some cases, the political views of self-described libertarians differ modestly from those of the general public; in others there are no differences at all.

In some cases, the political views of self-described libertarians differ modestly from those of the general public; in others there are no differences at all.

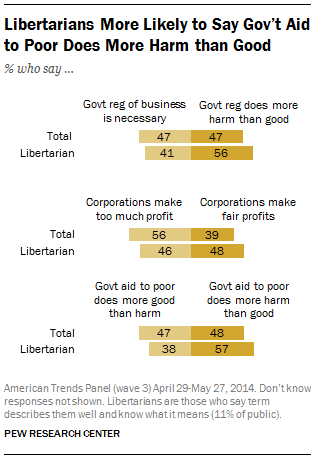

When it comes to attitudes about the size and scope of government, people who say the term libertarian describes them well (and who are able to correctly define the term) are somewhat more likely than the public overall to say government regulation of business does more harm than good (56% vs. 47%). However, about four-in-ten libertarians say that government regulation of business is necessary to protect the public interest (41%).

The attitudes of libertarians similarly differ from the public on government aid to the poor; they are more likely than the public to say “government aid to the poor does more harm than good by making people too dependent on government assistance” (57% vs. 48%), yet about four-in-ten (38%) say it “does more good than harm because people can’t get out of poverty until their basic needs are met.”

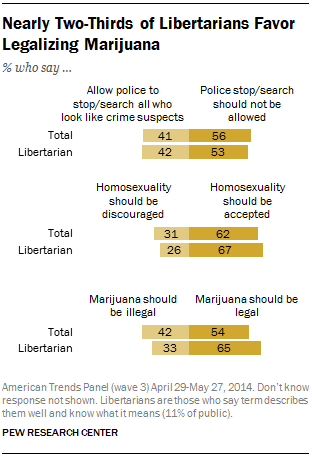

Libertarianism is associated with limited government involvement in the social sphere. In this regard, self-described libertarians are somewhat more supportive of legalizing marijuana than the public overall (65% vs. 54%).

Libertarianism is associated with limited government involvement in the social sphere. In this regard, self-described libertarians are somewhat more supportive of legalizing marijuana than the public overall (65% vs. 54%).

But there are only slight differences between libertarians and the public in views of the acceptability of homosexuality. And they are about as likely as others to favor allowing the police “to stop and search anyone who fits the general description of a crime suspect” (42% of libertarians, 41% of the public).

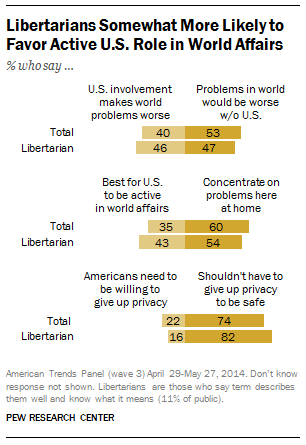

Similarly, self-described libertarians do not differ a great deal from the public in opinions about foreign policy. Libertarianism is generally associated with a less activist foreign policy, yet a greater share of self-described libertarians (43%) than the public (35%) think “it is best for the future of our country to be active in world affairs.”

Similarly, self-described libertarians do not differ a great deal from the public in opinions about foreign policy. Libertarianism is generally associated with a less activist foreign policy, yet a greater share of self-described libertarians (43%) than the public (35%) think “it is best for the future of our country to be active in world affairs.”

And in views of the tradeoff between defending against terrorism and protecting civil liberties, large majorities of both the public (74%) and self-described libertarians (82%) say “Americans shouldn’t have to give up privacy and freedom in order to be safe from terrorism.”

An alternative way to identify libertarians is the process used to create the Pew Research Center’s political typology, released in June (for more on how the political typology was created, read our explainer in Fact Tank). That study used a statistical technique called “cluster analysis” to sort people into homogeneous groups, based on their responses to 23 questions about a variety of social and political values.

None of the seven groups identified by the 2014 political typology closely resembled libertarians, and, in fact, self-described libertarians can be found in all seven. Their largest representation is among the group we call Business Conservatives; 27% of this group says the term libertarian describes them well. Business Conservatives generally support limited government, have positive views of business and the U.S. economic system, and are more moderate than other conservative groups on the issue of homosexuality. However, they are also supportive of an activist foreign policy and do not have a libertarian profile on issues of civil liberties.

In creating the political typology, many variations of the cluster analysis were run (e.g., varying the questions included and the number of clusters to be produced). Each was judged by how practical and substantively meaningful it was, with the final model judged to be strongest from a statistical point of view, most persuasive from a substantive point of view, and representative of the general patterns seen across the various cluster solutions (see “About the Political Typology” for more).

In the process of running several different models in creating the typology, we came up with one early version of the typology that had 12 groups, including a group that resembled libertarians. But the model was impractical, in part because it produced groups that were too small to analyze, and this set of groups did not persist across other models.

Under this one model, the group with a libertarian profile constituted about 5% of the public. They hold generally conservative views on the social safety net, regulation and business; liberal attitudes on homosexuality and immigration; and are less supportive of the use of military force when compared with the more conservative-leaning typology groups. They also are younger, on average, than most of the other groups (though a majority are 30 or older). But many members of this group diverge from libertarian thinking on key issues, including about half who say affirmative action is a good thing and that stricter environmental laws are worth the cost.

Here are the topline results and survey methodology. To see where you fit on the political spectrum, take our Political Typology Quiz.